How E. coli Use Fluid Flow and Channel Design to Swim Upstream and Trigger Infections

Bacteria are often imagined as passive organisms, simply drifting wherever fluids carry them. New research shows that this assumption is not only wrong but potentially dangerous. Scientists have uncovered how Escherichia coli (E. coli), a common bacterium responsible for many infections, can actively swim upstream against strong fluid flows, exploiting the shape of channels and the structure of moving liquids to invade the human body and contaminate medical devices.

At a time when antibiotic resistance is rising globally, these findings add an important piece to the puzzle of how infections begin and spread. According to global health projections from the United Nations, common bacterial infections could kill more people than cancer by 2050, making it crucial to understand not just how bacteria respond to drugs, but how they physically move and colonize environments inside the body.

Why Upstream Swimming Matters in Real Life

Inside the human body, fluids are constantly moving. Urine flows through the urinary tract, mucus moves through the respiratory system, and blood travels through an intricate network of vessels. For years, it was assumed that these flows help protect us by flushing bacteria away. However, researchers have now demonstrated that fluid flow can actually assist bacteria, allowing them to travel in the opposite direction and reach vulnerable tissues.

This upstream swimming behavior is especially relevant to urinary tract infections (UTIs), respiratory infections, and the contamination of medical and dental equipment such as catheters and tubing. If bacteria can move upstream efficiently, an infection detected in one part of the body may already be present much further along than symptoms suggest.

Recreating the Body’s Hidden Pathways

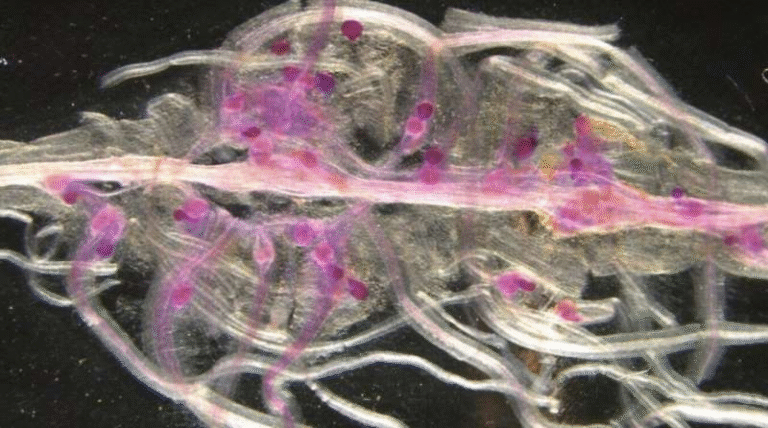

To understand how E. coli achieves this, researchers created nanofabricated, multichannel microtubes that closely resemble the narrow, maze-like passages found inside the body and in medical devices. These artificial channels allowed scientists to precisely control flow speed, channel width, and corner geometry, while tracking thousands of individual bacterial cells in real time.

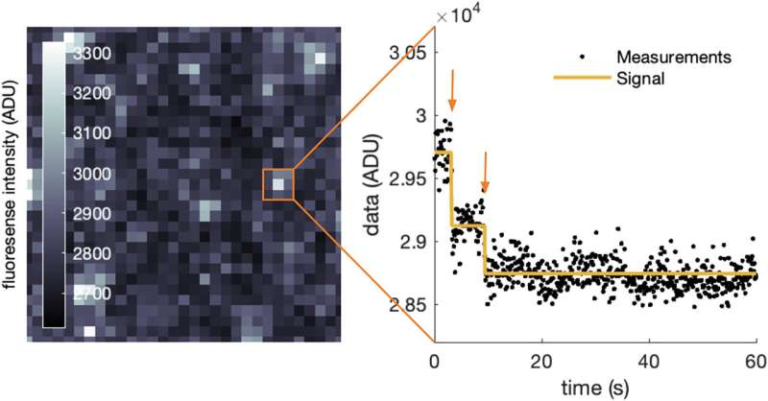

Using a combination of high-speed imaging, mathematical modeling, and computer simulations, the team analyzed how bacteria behaved under different conditions. This detailed approach made it possible to calculate something called bacterial flux, which measures how many cells successfully travel upstream over time.

Four Stages of Bacterial Invasion

The researchers found that upstream invasion does not happen randomly. Instead, it follows four distinct stages:

- Bacteria first escape from a colonized cavity, pushing against the direction of flow.

- They then migrate upstream through narrow connecting channels.

- Once they reach a new cavity, they spread and establish a fresh colony.

- Finally, the bacteria form larger structures that enhance further colonization.

Tracking thousands of cells across these stages revealed just how efficient E. coli can be when the conditions are right.

Channel Shape Can Make or Break an Infection

One of the most striking discoveries involved channel geometry. Smooth, rounded corners—similar to the soft surfaces found throughout much of the human body—turned out to be ideal pathways for bacteria. Along these gentle curves, E. coli could hug the walls, align themselves with the flow, and swim upstream with surprising ease.

In contrast, channels with sharp, angular corners dramatically reduced bacterial movement. The abrupt changes in direction disrupted swimming patterns and stalled bacterial progress, resulting in little to no contamination in those designs.

Channel width also played a role. Thinner channels made it harder for bacteria to take the critical first step of escaping a colonized area, while wider channels with faster flows were unexpectedly more vulnerable to invasion.

These insights suggest that medical devices do not need to sacrifice patient comfort to improve safety. Thin designs combined with intentional twists, turns, and sharp internal features could significantly reduce infection risk.

When Stronger Flow Makes Things Worse

Perhaps the most counterintuitive result was the role of fluid flow itself. Conventional wisdom says that stronger flow should wash bacteria away. Instead, the study showed that stronger flow can help bacteria move faster upstream.

The moving fluid acts like a guide rail, aligning bacterial cells in a favorable orientation and allowing them to ride the flow’s structure. Within minutes, the first cells were observed reaching the upstream end of the channels. Once there, these pioneer cells seeded new colonies and triggered what the researchers described as a two-way invasion.

After reaching upstream locations, bacteria formed streamer-like bioaggregates. These structures were then carried downstream by the flow, rapidly seeding the entire length of the channel. This process resulted in roughly a threefold increase in colonization speed compared to slower, cavity-by-cavity spread.

What This Means for UTIs and Medical Devices

These findings have serious implications for infections like UTIs. The presence of bacteria in the lower urinary tract may indicate that bacteria have already traveled much further, possibly reaching the kidneys before symptoms become severe. In such cases, fluid flow does not act as a protective barrier, but instead accelerates the infection.

Medical devices are another major concern. Catheters, stents, and dental equipment often feature smooth, rounded internal surfaces designed for comfort and efficiency. This research suggests that such designs may unintentionally encourage bacterial invasion, highlighting the need for a rethink in biomedical engineering.

Learning from Bacteria for Future Technology

Beyond infection prevention, the study opens doors to new technologies. The same physical strategies bacteria use to swim upstream could inspire microrobots capable of navigating fluid environments inside the body. These tiny machines could one day deliver drugs precisely where they are needed, guided by principles refined by bacteria over billions of years.

The mechanisms bacteria use to reorient themselves against flow are remarkably similar to those proposed for artificial microswimmers, making this an exciting area for biomimicry and medical innovation.

A Broader Look at Bacterial Motility

E. coli moves using flagella, whip-like structures that rotate to propel the cell forward. By alternating between straight runs and random reorientations, bacteria can adapt to complex environments. Near surfaces and under flow, subtle hydrodynamic effects allow them to maintain upstream motion even in challenging conditions.

Understanding these physical behaviors is just as important as studying genetics or biochemistry. Infection is not only a biological process, but also a mechanical and physical one, shaped by fluid dynamics and geometry.

Why This Research Matters Now

As antibiotic resistance continues to grow, preventing infections before they take hold is more important than ever. This study shows that design choices and physical environments play a major role in bacterial success. By adjusting how we build medical devices and understanding how bacteria exploit flow, we gain new tools in the fight against infection.

Rather than relying solely on drugs, future solutions may come from smarter engineering, inspired by the very organisms we are trying to stop.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newton.2025.100337