Queen Conch Hopping Behavior Is Shaping New Conservation Guidance for a Threatened Sea Snail

A newly published scientific study is offering fresh insight into how the queen conch (Aliger gigas) moves, gathers, and reproduces—and how those behaviors can be used to design more effective conservation strategies. The research, published in the journal Conservation Biology, focuses on the unique movement patterns of this large marine snail and proposes a clear, measurable spatial buffer that could help protect vulnerable breeding populations from overfishing and habitat disturbance.

The queen conch is a giant herbivorous marine snail found across the Caribbean and parts of the western Atlantic. It is both ecologically important and culturally significant, supporting local fisheries and playing a role in maintaining healthy seagrass ecosystems. Despite this importance, queen conch populations have declined sharply over recent decades, largely due to overharvesting and habitat loss, leading to its listing as Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Why Queen Conch Movement Matters

Unlike many snails that move slowly by crawling and leaving behind slime trails, queen conch have a surprisingly dynamic way of getting around. They move by hopping across the seafloor, using a strong, muscular foot to launch themselves upward and forward. This hopping behavior is not just a biological curiosity—it plays a central role in how conch form groups, known as aggregations, which are critical for reproduction and protection from predators.

These aggregations, however, come with a downside. When conch gather in large numbers, they become easy targets for fishers, making them especially vulnerable to targeted overfishing. Understanding how far conch move while forming and maintaining these groups is therefore essential for designing conservation measures that actually work in the real world.

Tracking Conch on the Move

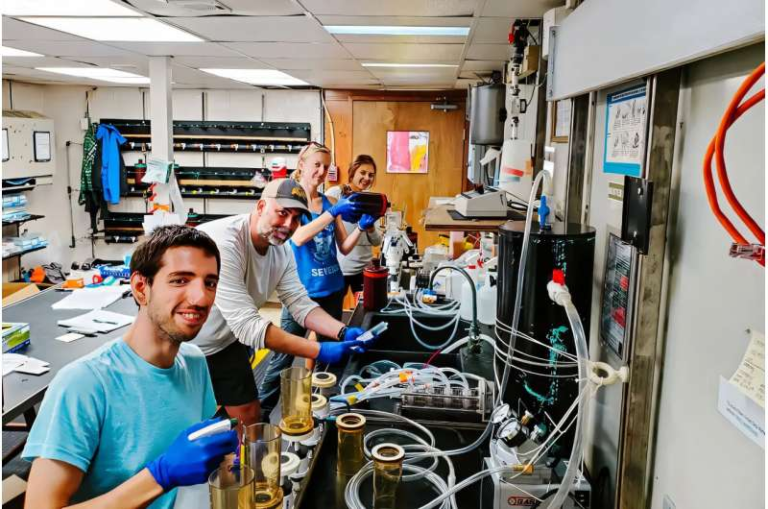

To study these behaviors in detail, researchers from Shedd Aquarium and the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve used a combination of field observations, custom-built tracking devices, large-scale surveys, and mathematical modeling.

At sea, scientists and trained volunteers conducted underwater observations from Shedd Aquarium’s research vessel, the R/V Coral Reef II. They carefully watched adult conch in their natural habitat and measured hundreds of individual hops, documenting how far and how often the animals moved.

In addition to direct observation, the team developed and deployed custom biologgers, which were attached to 42 adult conch at two study sites off the coast of Florida. These biologgers were designed to detect when a conch was actively hopping and moving versus when it remained still. The devices collected movement data across different habitats and seasons, providing a detailed picture of conch activity over time.

The research did not stop in Florida. Divers also carried out extensive underwater surveys in The Bahamas, mapping queen conch distributions across hundreds of kilometers of seafloor. These surveys helped reveal why conch populations tend to appear in patchy, uneven clusters rather than being spread evenly across suitable habitat.

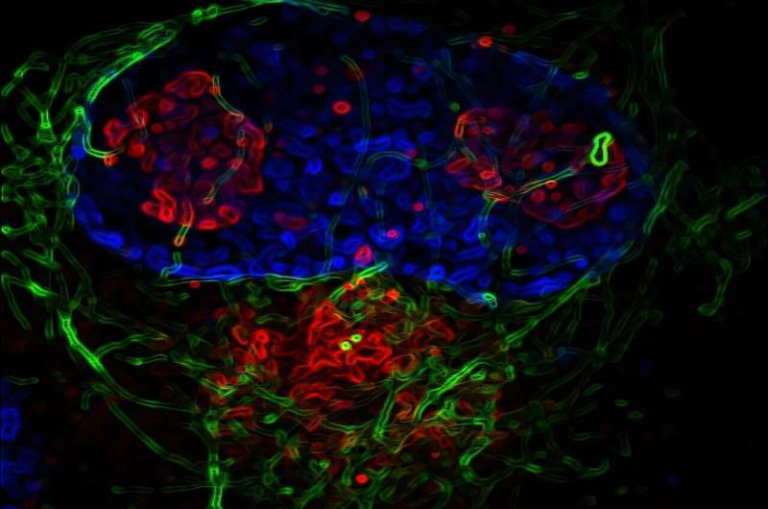

Finally, the researchers combined all of this information using mathematical models. These models linked individual movement behavior to larger patterns of aggregation size, spatial distribution, and habitat use.

The 330-Meter Conservation Buffer

One of the study’s most important findings is a clear, actionable recommendation for conservation management. Based on observed movement patterns and modeled aggregation behavior, the researchers determined that a 330-meter spatial buffer around breeding aggregations would be sufficient to protect the core area conch use for reproduction.

To help visualize this distance, the researchers compared it to the height of the Eiffel Tower. While 330 meters may sound modest, it is large enough to encompass the typical movement range of adult conch during breeding periods, while still being small enough to manage locally.

This recommendation is especially valuable because many conservation policies struggle to translate scientific data into practical on-the-ground rules. A clearly defined buffer zone offers resource managers a tool they can actually implement—whether by restricting fishing, limiting boat traffic, or minimizing habitat disruption within that radius.

Filling a Management Gap

Although queen conch are protected under federal law in the United States, conservation managers often face a lack of specific, behavior-based guidance on how to protect the species effectively. Broad protections alone do not always prevent localized overfishing or damage to key breeding sites.

By identifying the minimum space needed to safeguard breeding aggregations, this study helps bridge that gap. The proposed buffer zones are flexible enough to be applied in response to dynamic threats, such as sudden increases in fishing pressure or localized habitat destruction, without requiring large, permanent marine protected areas.

Why Queen Conch Are Ecologically Important

Beyond their economic and cultural value, queen conch play a significant role in marine ecosystems. As herbivores, they graze on algae growing on seagrass beds, helping maintain healthy seagrass ecosystems that serve as nurseries for many fish species. These seagrass habitats also help stabilize sediments and improve water quality.

When conch populations decline, the effects can ripple outward, impacting not just fisheries but the overall balance of coastal ecosystems.

Broader Conservation Context

The findings from this study align with a growing trend in conservation science that emphasizes behavior-informed management. Instead of relying solely on species listings or catch limits, researchers are increasingly looking at how animals actually use space and resources.

In the case of queen conch, movement behavior directly influences where protection should be focused. The study also complements ongoing research into population connectivity, larval dispersal, and genetic structure, which together help determine how local protections can contribute to regional population recovery.

Looking Ahead

This research provides a strong example of how innovative technology, such as custom biologgers, can unlock new insights into species that are otherwise difficult to study. It also demonstrates the value of combining fieldwork, long-distance surveys, and modeling to answer complex ecological questions.

Most importantly, the study shows that even a slow-moving sea snail can offer fast, actionable lessons for conservation—if scientists pay close attention to how it moves.

For people interested in supporting queen conch conservation, Shedd Aquarium also encourages public advocacy to maintain protections under the Endangered Species Act, emphasizing that science-backed policy plays a critical role in long-term species survival.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.70203