How Marine Viruses Help Fuel Underwater Oxygen-Rich Zones

New scientific research is revealing a side of viruses that many people don’t expect. Instead of being just agents of disease and destruction, certain marine viruses are now shown to play a key role in boosting ocean productivity and oxygen levels beneath the sea surface. A newly published interdisciplinary study led by researchers from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the University of Maryland explains how viral infections in ocean microbes help create oxygen-rich zones that persist for months at a time.

At the center of this research is a microscopic but powerful interaction between viruses and cyanobacteria, specifically a type of blue-green algae known as Prochlorococcus. This organism is one of the most abundant photosynthetic life forms on Earth and is responsible for a significant portion of the ocean’s oxygen production. What the new study shows is that when viruses infect these microbes, the result isn’t simply microbial death. Instead, viral activity can stimulate nutrient recycling, enhance microbial growth, and ultimately contribute to higher oxygen levels in the water column.

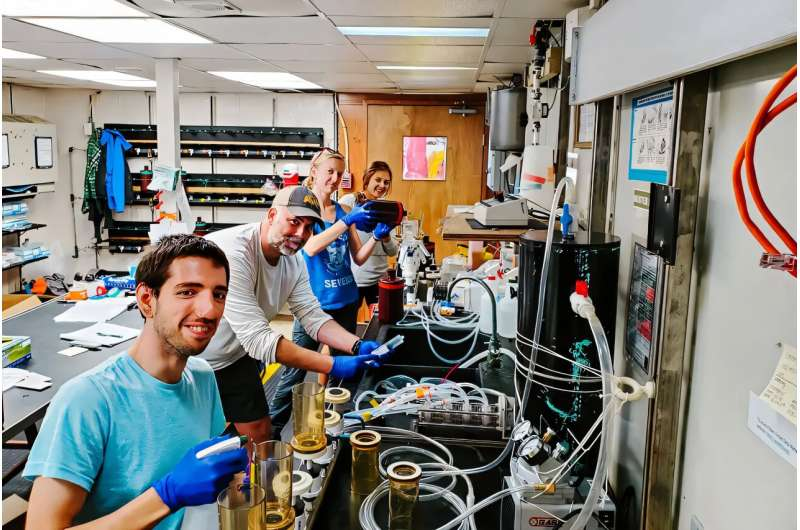

The research cruise that made the discovery possible

The findings come from a major research expedition to the Sargasso Sea, a region of the North Atlantic Ocean known for its clear waters and long-term scientific monitoring. The study was carried out during a National Science Foundation-funded research cruise aboard the research vessel Atlantic Explorer in October 2019. The cruise focused on the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study, a monitoring program that has been collecting physical, chemical, and biological ocean data for nearly four decades.

Scientists aboard the ship worked around the clock, collecting samples from marine surface waters and slightly deeper layers. These samples were used for RNA sequencing surveys, allowing researchers to analyze microbial activity, viral infections, and biological functions over day-night cycles. After being frozen onboard, the samples were transported back to laboratories at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and collaborating institutions for detailed analysis.

The research team included faculty members and students from UT, along with collaborators from the University of Maryland, Georgia Institute of Technology, Ohio State University, and the Technion Institute of Technology in Israel. This broad collaboration allowed the team to combine expertise in microbiology, oceanography, ecology, and data science.

A hidden ribbon of oxygen below the surface

One of the most striking findings from the study is the explanation behind a subsurface oxygen maximum, a band of water located roughly 50 meters below the ocean surface that contains unusually high levels of dissolved oxygen. This oxygen-rich zone spans several meters in thickness and appears seasonally, lasting for several months each year.

Previously, scientists observed this oxygen maximum but did not fully understand what drove its formation. The new research shows that viral infection of Prochlorococcus plays a significant role. When viruses infect these cyanobacteria, they cause cells to rupture, releasing nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, and other organic compounds into the surrounding water. Rather than being lost, these nutrients become fuel for other microbes in the ecosystem.

This nutrient release enhances microbial growth and productivity, which in turn supports additional photosynthesis and oxygen production at depth. The result is a sustained oxygen-rich layer beneath the surface, driven at least in part by viral activity.

Connecting the viral shunt and the microbial loop

A major contribution of this study is the clear connection it establishes between two foundational concepts in ocean ecology: the viral shunt and the microbial loop.

The viral shunt, first described in 1999, refers to the process by which viruses infect and destroy microbes, redirecting organic matter away from larger organisms and back into the pool of dissolved nutrients. This material is then reused by bacteria and other microorganisms rather than moving up the traditional food chain.

The microbial loop describes how microbes recycle organic matter, converting it back into forms that support primary production and sustain marine ecosystems.

By analyzing large-scale data on cellular and viral activity, including infection status and viral abundance, the researchers were able to identify how viral infections leave a measurable imprint on the ecosystem. The study shows that viral activity enhances nutrient recycling within the microbial loop, effectively linking viral processes to oxygen production and ecosystem-level functioning below the ocean surface.

Why viruses matter more than we thought

Viruses are often viewed only as harmful agents, but this research reinforces the idea that they are integral players in Earth’s ecosystems. In the ocean, viruses are incredibly abundant, with millions present in every milliliter of seawater. Their interactions with microbes influence carbon cycling, nutrient availability, and now, clearly, oxygen dynamics.

The study highlights that viral infection is not always about causing disease. In many cases, viral activity stimulates growth and productivity by accelerating the recycling of nutrients. This perspective challenges traditional assumptions and emphasizes that the ocean is fundamentally a microbial-driven system, where even the smallest organisms have outsized impacts.

The role of Prochlorococcus in ocean oxygen

Understanding this study also requires appreciating the importance of Prochlorococcus itself. This cyanobacterium thrives in nutrient-poor, sunlit regions of the ocean and is one of the most efficient photosynthetic organisms known. It plays a critical role in global oxygen production and carbon fixation.

When viruses infect Prochlorococcus, the released cellular contents don’t go to waste. Instead, they feed surrounding microbes, creating a feedback loop that supports continued productivity. This process helps explain how oxygen-rich zones can persist even below the surface, where light levels are lower.

Broader implications for ocean science and climate research

The findings have important implications beyond the Sargasso Sea. Similar subsurface oxygen maxima exist in other parts of the world’s oceans, and viral processes may be influencing these systems as well. Understanding how viruses shape oxygen and nutrient dynamics is especially relevant as climate change alters ocean temperature, stratification, and circulation.

As oceans warm and nutrient patterns shift, microbial interactions—including viral infections—may change in ways that affect oxygen distribution and carbon cycling. Studies like this provide crucial insight into how microscopic processes scale up to influence global biogeochemical cycles.

A new way of looking at marine viruses

This research adds to a growing body of evidence that viruses are not just destroyers but drivers of ecological balance in the ocean. By catalyzing nutrient recycling and supporting microbial productivity, they help maintain oxygen-rich environments that benefit the broader marine ecosystem.

The study also demonstrates the power of long-term monitoring programs and interdisciplinary collaboration. By combining decades of ocean data with modern molecular techniques, researchers are uncovering hidden processes that shape the planet’s largest ecosystem.

As ocean science continues to evolve, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: to understand how the oceans breathe, we must pay close attention to the tiny viruses working behind the scenes.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67002-1