Silky Shark Tagging Study Reveals Gaps in Marine Protected Areas

A new international study on silky sharks is drawing attention to an uncomfortable reality about ocean conservation: even large and well-known marine protected areas are not enough to fully protect highly mobile species. The research focuses on the silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), one of the ocean’s most wide-ranging predators, and shows that current marine protected areas (MPAs) offer only partial protection for this vulnerable species.

Silky sharks are among the most common pelagic sharks in tropical oceans, yet their populations have been declining rapidly. Commercial fishing pressure and the global shark fin trade continue to pose serious threats, and understanding how these sharks move across the ocean is essential if conservation efforts are going to work. This new study provides some of the most detailed insights so far into where silky sharks actually spend their time—and where they remain dangerously exposed.

Tracking silky sharks across the Eastern Tropical Pacific

The study, titled “Pelagic sharks in parks: Marine protected areas in the Eastern Tropical Pacific provide limited protection to silky sharks tracked from the Galapagos Marine Reserve,” was published in the journal Biological Conservation. It represents the first detailed assessment of how silky sharks use marine protected areas in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP).

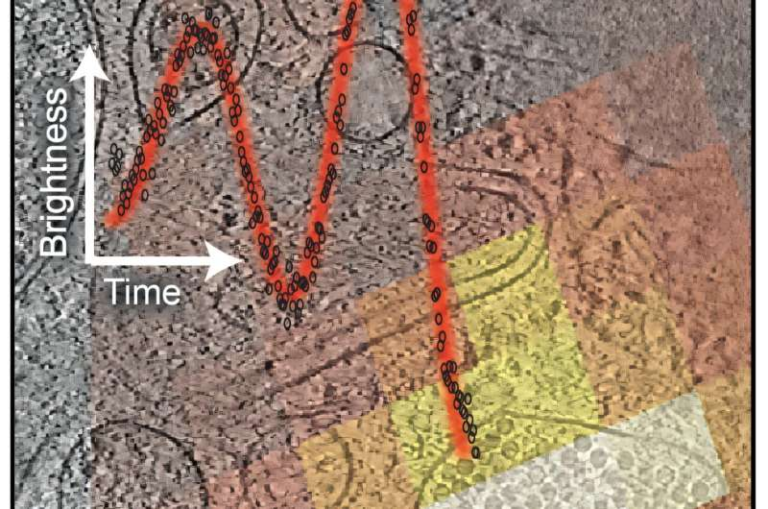

Researchers from the Guy Harvey Research Institute, the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center, the Charles Darwin Foundation, and the Galapagos National Park Directorate collaborated on the project. Over nearly two years, they tracked the movements of 40 adult silky sharks using fin-mounted satellite tags.

Of the sharks tagged, 33 were females and seven were males. Ten sharks were tagged in February 2021 near Darwin Island, followed by another 30 in July 2021, with 14 tagged off Darwin Island and 16 near Wolf Island. These islands sit within the Galápagos Marine Reserve (GMR), one of the most famous MPAs in the world, covering approximately 133,000 square kilometers.

How much time do silky sharks spend in protected waters?

One of the most striking findings of the study is that silky sharks spent less than half of their time inside the Galápagos Marine Reserve. On average, the sharks were within the GMR for about 47% of the tracking period. For the remaining time, they traveled well beyond the boundaries of the reserve, entering waters where fishing pressure is much higher.

The researchers also found that the sharks made very limited use of other recently established MPAs in the region, particularly those located to the east of the Galápagos. These newer protected areas were partly designed to safeguard movement corridors for large pelagic species, but the data suggests they are not aligning well with the actual movement patterns of silky sharks.

Once the sharks leave protected waters, they face significant risks from industrial longline and purse-seine fisheries. Silky sharks are among the most heavily fished shark species in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and they are frequently caught as bycatch in tuna fisheries. Even when they are not the target species, they are often retained for their valuable meat and fins.

A species under serious pressure

Silky sharks are currently listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Global data shows that their populations have declined by 47–54% over the past 30 to 40 years, largely due to overfishing. Their fins rank as the second most common shark species found in the international fin trade, underscoring how heavily exploited they are worldwide.

The study highlights just how exposed silky sharks are when they roam the high seas. Their nomadic lifestyle, which allows them to cover enormous distances, also puts them directly in the path of fishing fleets operating outside protected zones.

In one remarkable example from the study, a silky shark tagged near Wolf Island in 2021 traveled a record-breaking 27,666 kilometers (17,190 miles) in less than two years. This extraordinary journey illustrates both the species’ incredible mobility and the difficulty of protecting it with fixed marine reserves alone.

Directional migrations raise new concerns

Another important finding from the research is the directional nature of silky shark migrations. When sharks left the Galápagos Marine Reserve, they tended to travel west and northwest, rather than east toward other MPAs. Unfortunately, these western and northwestern areas are largely unprotected and experience intense industrial fishing activity, particularly purse-seine and longline operations.

While it is encouraging that silky sharks spend a substantial amount of time inside the GMR—where industrial fishing is prohibited—the fact that their preferred migration routes take them into heavily fished waters raises serious conservation concerns. The study suggests that expanding MPAs to the west and northwest of the Galápagos could significantly improve protection for this overfished species.

MPAs alone are not enough

Between 2010 and 2023, 53 marine protected areas were created across the Central and South American Pacific, covering more than 2.5 million square kilometers. These MPAs now make up about 90% of the region’s protected area network. In addition, during the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), Panama, Ecuador, Colombia, and Costa Rica agreed to work together on creating even larger protected areas.

Despite these efforts, the study makes it clear that MPAs by themselves will not reverse silky shark population declines. The Eastern Tropical Pacific supports major commercial fisheries, particularly tuna fisheries that rely on purse-seine nets and longlines. Both fishing methods are associated with high levels of bycatch, affecting marine mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, and sharks.

Silky sharks are especially vulnerable to purse-seine fisheries that use fish aggregating devices (FADs)—floating structures that attract fish in the open ocean and unintentionally draw in sharks.

The researchers emphasize that MPAs need to be paired with stronger fisheries management, particularly in waters surrounding protected areas and along biological corridors. Without coordinated international action on fishing practices, highly migratory species like silky sharks will continue to face serious risks.

What we still don’t know about silky sharks

One of the more sobering points raised by the study is how little scientists still know about silky sharks. Key aspects of their life history—such as where they mate or give birth—remain largely unknown. This lack of basic biological information makes it even harder to design effective conservation strategies.

Improving our understanding of silky shark movement patterns, breeding areas, and habitat use is critical. Better data would allow policymakers to designate MPAs more strategically and implement management measures that reflect how these animals actually use the ocean.

Why silky sharks matter

Silky sharks play an important role as apex and mesopredators in pelagic ecosystems. By regulating prey populations, they help maintain balance in open-ocean food webs. Their decline can trigger cascading effects that impact the health of entire marine ecosystems.

The study also highlights a broader issue in ocean conservation: many protected areas were designed with static boundaries, while marine animals live in a dynamic and constantly changing environment. For wide-ranging species like silky sharks, conservation solutions need to extend beyond fixed borders.

Looking ahead

This research sends a clear message. Marine protected areas are valuable and necessary, but for species like silky sharks, they are only part of the solution. Expanding MPAs in the right locations, improving fisheries management on the high seas, and filling critical knowledge gaps about shark biology are all essential steps forward.

As one-third of all pelagic sharks and rays are now threatened with extinction, the findings from this study are both timely and urgent. Protecting silky sharks will require cooperation across national boundaries and a willingness to rethink how ocean conservation is done.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111658