Catastrophic Heat Wave Wiped Out Two Endangered Corals in the Florida Keys and Raised Serious Questions About the Reef’s Future

Once celebrated as a vibrant underwater ecosystem, large portions of the Florida Coral Reef now resemble silent graveyards. Following an extreme marine heat wave during the summer of 2023, scientists confirmed the total functional collapse of two endangered coral species—elkhorn coral and staghorn coral—across much of the Florida Keys and the Dry Tortugas. These corals were not just visually striking; they were foundational to the reef’s structure and survival. Their loss marks one of the most severe ecological setbacks the region has ever experienced.

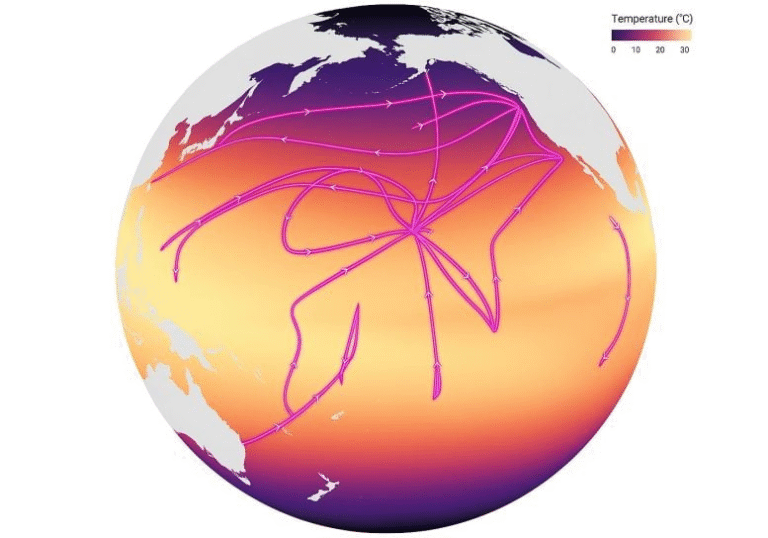

The heat wave that triggered this collapse was unprecedented in both intensity and duration. Ocean temperatures soared during July and August 2023, creating the hottest summer conditions the Florida reef has experienced in more than 150 years. As water temperatures remained elevated for weeks, coral colonies began to bleach at alarming rates. Bleaching occurs when corals expel their symbiotic algae due to stress, stripping them of both color and their primary source of energy. In this case, bleaching quickly turned fatal.

Researchers affiliated with Mission: Iconic Reefs, a large-scale coral restoration program led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), closely monitored the unfolding disaster. Scientists from Florida International University (FIU) played a key role in surveying the damage. When temperatures finally dropped and researchers returned to assess survival, they found that not a single elkhorn or staghorn coral had survived in many monitored areas. The findings were later published in the journal Science, confirming what many feared: these species had reached functional extinction in the region.

Functional extinction does not necessarily mean that every individual coral is gone, but it does mean that populations are now too small and fragmented to perform their essential ecological roles. Elkhorn and staghorn corals are known as reef builders. Their branching structures create complex habitats that shelter fish, crustaceans, and countless other marine organisms. They also act as natural breakwaters, reducing wave energy before it reaches Florida’s coastline. Without them, the reef loses both biodiversity and structural integrity.

The disappearance of these corals has ripple effects throughout the ecosystem. Reef fish that relied on the branching corals for shelter are left exposed to predators. Algae can more easily overgrow dead coral skeletons, further preventing reef recovery. Over time, the physical reef itself begins to erode, weakening its ability to protect shorelines from storm surge and flooding. This has direct implications for coastal communities, which have long depended on the reef as a natural defense system.

The economic consequences are also significant. Florida’s coral reefs support tourism, fishing, and recreation industries worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Snorkelers and divers visiting the Keys often expect to see lush coral gardens like those featured in tourism brochures. However, the reality on the seafloor has changed dramatically. The massive, iconic coral formations that once defined the region are now largely gone, replaced by broken skeletons and sparse survivors.

Despite the scale of loss, scientists are not viewing the event as the end of the story. Researchers are now focusing intensely on understanding why some coral colonies elsewhere managed to survive the same heat wave. Even within Florida waters, survival varied depending on location, depth, water flow, and habitat conditions. By studying these differences, scientists hope to identify traits or environments that provide better protection against thermal stress.

One major area of investigation involves coral genetics. Not all corals respond to heat stress in the same way. Some genotypes appear to be more heat-tolerant, and identifying these could help guide future restoration efforts. Scientists are also studying the role of symbiotic algae, which live inside coral tissue and provide energy through photosynthesis. Different strains of algae offer varying levels of heat resistance, and swapping or enhancing these partnerships could improve coral survival during future heat waves.

Another strategy under consideration is assisted gene flow. This involves introducing genetic material from coral populations in warmer regions, such as Honduras, where corals may already be adapted to higher temperatures. By crossbreeding or transplanting these corals, researchers hope to increase the thermal tolerance of Florida’s reef populations. These approaches are complex and carefully regulated, but they are increasingly seen as necessary in a rapidly warming ocean.

Mission: Iconic Reefs continues to play a central role in these efforts. The initiative combines field restoration, long-term monitoring, and laboratory research to better understand coral resilience. FIU’s Institute of Environment supports both restored and wild coral studies, collecting data that helps scientists evaluate which restoration techniques are most effective. This includes analyzing outplanting methods, site selection, and genetic diversity to maximize survival chances.

Importantly, scientists emphasize that restoration alone cannot solve the problem. Marine heat waves are becoming more frequent and more intense due to climate change. Without significant reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, even the most advanced restoration techniques may struggle to keep pace with rising ocean temperatures. The 2023 event is widely viewed as a warning signal, highlighting how close many reef systems are to ecological tipping points.

At the same time, researchers stress that the situation is not hopeless. Coral reefs have survived dramatic changes in the past, and science is advancing rapidly. By learning from the few survivors, preserving genetic diversity, and refining intervention strategies, there is still potential to rebuild portions of the reef in a way that is better suited to future conditions. The focus now is on making intentional, evidence-based decisions rather than attempting to recreate the past exactly as it was.

The loss of elkhorn and staghorn corals in the Florida Keys represents one of the most sobering marine conservation stories in recent years. It underscores the vulnerability of even well-studied and actively managed ecosystems to extreme climate events. At the same time, it has sparked renewed urgency, collaboration, and innovation within the scientific community. What happens next will shape not only the future of Florida’s reefs, but also global approaches to coral conservation in a warming world.

Research paper reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adp4567