First Extensive Study Into Marsupial Gut Microbiomes Reveals New Microbial Species and Antimicrobial Resistance

Marsupials are some of the most recognizable mammals on the planet, strongly associated with Australia’s unique wildlife. Kangaroos, koalas, possums, and gliders are instantly familiar animals, yet despite their popularity, one major aspect of their biology has remained surprisingly underexplored: their gut microbiomes. A new large-scale scientific study has now taken a deep dive into this hidden world, offering the most comprehensive look so far at the bacteria and viruses living inside marsupial digestive systems.

This research represents the first extensive metagenomic survey of marsupial gut microbiomes and provides important insights into evolution, diet adaptation, conservation, and emerging health concerns such as antimicrobial resistance.

Why Marsupial Microbiomes Matter

Gut microbiomes play a crucial role in animal health. They help break down food, support immune systems, and influence overall metabolism. In many mammals, microbiomes are shaped by millions of years of co-evolution between hosts and microbes. Marsupials are particularly interesting in this context because they evolved in relative geographic isolation, mainly in Australia, and many species survive on extremely challenging diets.

Some marsupials, like koalas and greater gliders, feed largely or exclusively on eucalyptus leaves, which are toxic to most mammals. Understanding how gut microbes help marsupials process such diets can reveal how animals adapt to extreme ecological niches and how sensitive these systems may be to environmental or human-driven changes.

Scope and Scale of the Research

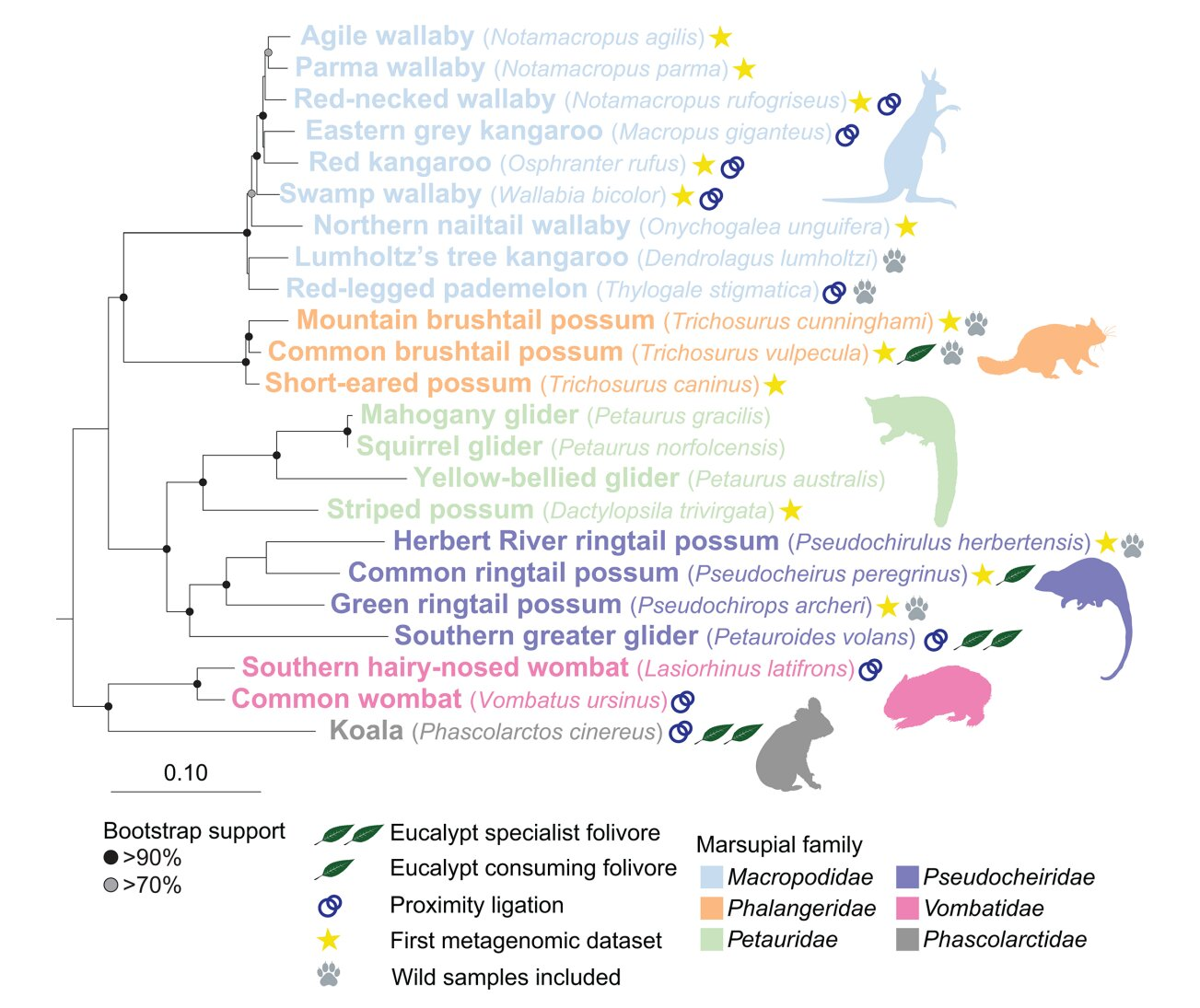

The study was led by researchers from the University of Queensland (UQ), working in collaboration with scientists from Denmark and the United States. To ensure a broad and representative dataset, the team collected fecal samples from 98 marsupials in total, covering 23 different species.

Of these samples, 82 came from captive marsupials living in wildlife sanctuaries, while 16 were collected from wild individuals inhabiting forested regions around Queensland. This dual sampling approach allowed researchers to directly compare microbiomes shaped by natural environments versus those influenced by captivity and human care.

The research was published in the peer-reviewed journal Microbial Genomics, underscoring its scientific rigor and significance.

A First-Ever Molecular Inventory for Many Species

One of the most striking outcomes of the study is that it provides the first metagenomic data for 13 of the 23 marsupial species examined. This includes well-known animals such as the red kangaroo and the common brushtail possum.

Using metagenomic sequencing, researchers were able to analyze the collective DNA of bacteria and viruses present in the samples. This approach does not rely on growing microbes in a lab, which is crucial because many gut microbes cannot be easily cultured. As a result, the team uncovered an extraordinary level of previously undocumented microbial diversity, including many bacterial and viral genomes that are likely new to science.

What Shapes a Marsupial’s Gut Microbiome?

The study found that marsupial gut microbiomes vary significantly depending on several factors. Host family, geographic location, and diet all played important roles in shaping microbial communities.

Closely related species tended to have more similar microbiomes, suggesting long-term evolutionary relationships between marsupials and their gut microbes. However, environmental factors and feeding habits introduced additional layers of variation, highlighting how flexible and responsive these microbial ecosystems can be.

Insights Into Eucalyptus Digestion

One of the key questions the researchers explored was how different marsupials adapt to eating eucalyptus, a food source rich in toxic compounds and low in nutritional value. The team compared microbiomes from specialist eucalyptus feeders, such as koalas and southern greater gliders, with those from species that consume eucalyptus more generally, including common and golden brushtail possums and common ringtail possums.

The results showed clear and significant differences in microbial abundance and composition between these groups. Even more interestingly, the two specialist eucalyptus feeders were not microbiologically identical. Koalas and greater gliders each exhibited distinct gut microbiome signatures, reflecting adaptations to digesting different species or types of eucalyptus leaves.

This finding suggests that gut microbes have evolved in highly specific ways to support dietary specialization, even among animals that appear to share similar feeding strategies.

Antimicrobial Resistance Raises Red Flags

While much of the study revealed fascinating evolutionary and ecological insights, one finding raised serious concerns. Researchers detected a higher prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes in the gut microbiomes of some captive marsupials compared to their wild counterparts.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms to survive antibiotic treatments. In wildlife sanctuaries, antibiotics are sometimes necessary to treat infections, but their use can unintentionally alter gut microbiomes and promote resistant microbial populations.

The study suggests that human intervention, particularly antibiotic use in captive settings, is a likely driver of this pattern. This does not mean treatment should stop, but it highlights the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship to avoid long-term health risks for animals and broader ecological consequences.

Practical Implications for Conservation and Veterinary Care

These findings have immediate relevance for wildlife conservation and veterinary medicine. By comparing wild and captive microbiomes, researchers can help veterinarians make more informed treatment decisions and design better antibiotic management protocols for marsupials in care.

For threatened species, maintaining a healthy and balanced gut microbiome could be essential for survival, especially when animals are rehabilitated or prepared for reintroduction into the wild. Understanding which microbial communities are natural and beneficial provides a valuable benchmark for assessing animal health.

What Comes Next for Marsupial Microbiome Research?

The researchers emphasize that this study is just the beginning. While metagenomic data reveals what microbes are present, it does not fully explain what those microbes are doing. The next phase of research will focus on isolating and characterizing key microbial species to better understand their functional roles.

Future studies may explore how specific microbes contribute to eucalyptus digestion, immune system regulation, or resistance to disease. There is also growing interest in understanding how environmental changes, habitat loss, and climate stress could disrupt these finely balanced microbial ecosystems.

Why This Study Matters Beyond Marsupials

Although the focus is on marsupials, the implications extend far beyond Australia’s wildlife. This research adds to a growing body of evidence showing that gut microbiomes are deeply intertwined with evolution, diet, and human activity. It also reinforces concerns about antimicrobial resistance as a global issue that affects not only humans but also wildlife and ecosystems.

By expanding our understanding of host-microbe relationships in lesser-studied animals, studies like this help build a more complete picture of life on Earth and the invisible biological networks that sustain it.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.001601