Scientists Measure Cellular Membrane Thickness Inside Cells for the First Time

Scientists have known for decades that cellular membranes are not all built the same. Some are thicker, some thinner, and those differences matter because membranes control how cells function. Until recently, however, actually measuring membrane thickness inside real, intact cells was impossible. Researchers had to rely on simplified lab models that stripped membranes of their natural complexity. That limitation has now been overcome.

A research team at Scripps Research has developed a method that allows scientists to measure cellular membrane thickness directly inside cells for the first time. This achievement provides an entirely new way to examine how membranes vary across organelles, how proteins influence membrane structure, and how subtle physical differences may affect cell health and disease.

The study was published in the Journal of Cell Biology under the title Surface Morphometrics reveals local membrane thickness variation in organellar subcompartments. It builds on earlier computational work and combines advanced imaging with powerful data analysis to reveal details that were previously invisible.

Why measuring membrane thickness has been so difficult

Cellular membranes are thin, flexible bilayers made mostly of lipids and proteins. Their thickness typically measures just a few nanometers, making them extremely challenging to study. For years, scientists could only measure membrane thickness using artificial systems, such as lipid bilayers formed in test tubes or membranes stripped of proteins.

While these systems were useful, they did not reflect what actually happens inside living cells. Real membranes are crowded with proteins, shaped by surrounding structures, and constantly changing. Measuring thickness in that environment required not only high-resolution imaging but also a way to analyze complex three-dimensional data.

That gap is what the Scripps Research team set out to close.

The Surface Morphometrics approach

The breakthrough comes from a computational pipeline called Surface Morphometrics, originally developed in the laboratory of Danielle Grotjahn, an associate professor at Scripps Research and the senior author of the study. The method combines cryo-electron tomography with advanced geometric analysis.

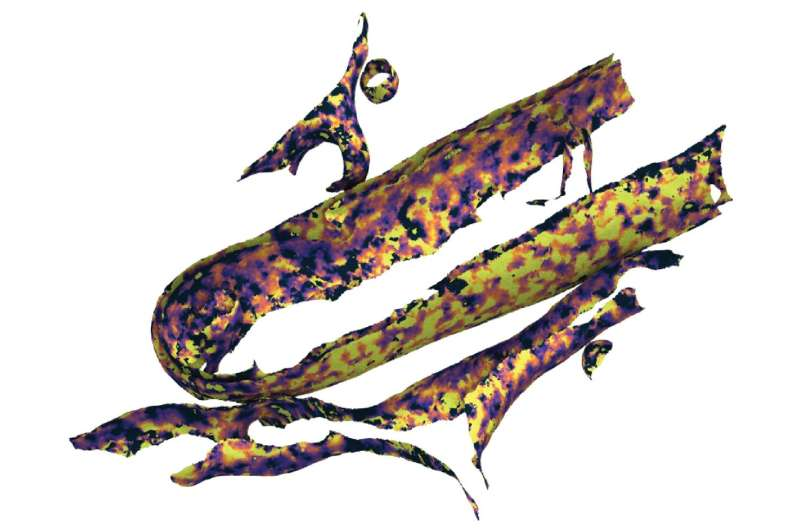

Cryo-electron tomography allows scientists to image cells frozen in a near-native state, preserving cellular structures without chemical fixation. From these images, researchers reconstruct detailed three-dimensional maps, known as tomograms. The Surface Morphometrics pipeline then converts those maps into triangle mesh models of cellular membranes.

By measuring the distance between lipid head groups across the membrane surface, the method provides precise, localized measurements of membrane thickness inside intact cells. This approach works at a resolution high enough to detect even subtle variations across small membrane regions.

What the researchers discovered

Using this method, the team examined membranes in animal cells and yeast cells, focusing particularly on mitochondria, the organelles responsible for energy production.

One of the clearest findings was that mitochondrial membranes differ significantly in thickness. The outer mitochondrial membrane was consistently thinner than the inner mitochondrial membrane across both cell types. This difference likely reflects variations in lipid composition and protein density, as the inner membrane hosts many protein complexes involved in energy generation.

Within the inner mitochondrial membrane itself, thickness was not uniform. Specialized folds known as cristae were found to have thicker membranes than regions of the inner membrane that lie close to the outer membrane. These structural differences may be crucial for how mitochondria generate and regulate energy.

The study also revealed a strong relationship between membrane curvature and thickness. Regions of membrane with higher curvature often showed distinct thickness profiles, suggesting that membrane-shaping proteins may influence both curvature and physical structure at the same time.

Patch-based analysis and protein interactions

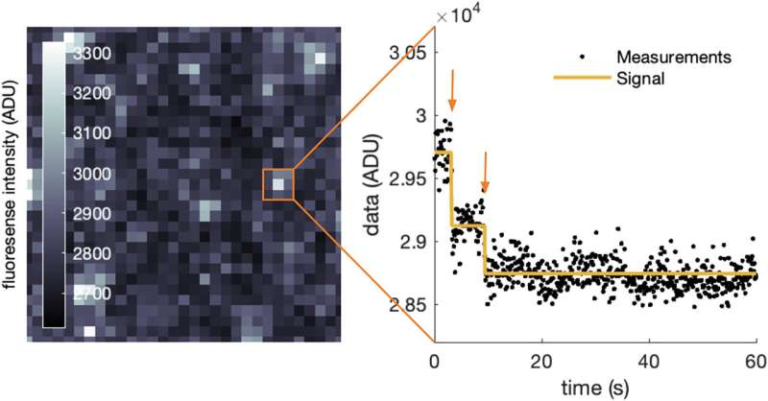

Beyond global measurements, the Surface Morphometrics pipeline includes a powerful feature known as patch-based analysis. This approach was developed by Ya-Ting “Atty” Chang, a graduate student and co-first author of the study.

Patch-based analysis works by isolating small, circular regions of membrane surrounding a specific protein of interest. These patches can then be compared to nearby membrane areas that lack the protein. The technique allows researchers to see how individual proteins are associated with changes in membrane thickness, curvature, or other physical properties.

Using this method, the team analyzed ATP synthase, a critical enzyme complex that produces cellular energy. They found that ATP synthase tends to cluster in membrane regions that are both highly curved and unusually thick. This pattern had never been observed before and highlights how proteins and membranes shape each other in highly specific ways.

Importantly, patch-based analysis also opens the door to discovering previously unknown membrane-associated proteins. By scanning for unusual thickness or curvature patterns, researchers may be able to identify protein activity even before the protein itself is fully characterized.

Why membrane thickness matters

Membrane thickness is not just a structural detail. It directly influences how proteins embed within membranes, how molecules move across them, and how organelles carry out specialized tasks.

Proteins are often tuned to function best within membranes of a certain thickness. If the membrane is too thick or too thin, protein structure and activity can be disrupted. This means that even small changes in membrane thickness can have outsized biological effects.

Understanding these variations inside real cells helps explain why different organelles behave differently, even though they are built from similar basic components. It also provides a new framework for studying how cells adapt to stress, change during development, or malfunction in disease.

Implications for disease research and drug development

Many diseases are associated with changes in membrane composition or structure. Mitochondrial disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, viral infections, and metabolic conditions all involve membranes in some way.

The ability to measure membrane thickness in intact cells offers a new tool for identifying subtle structural changes that may contribute to disease. It also has potential implications for drug development, particularly for drugs that target membrane-associated proteins. Knowing the physical environment those proteins operate in could improve drug design and effectiveness.

Expanding what scientists can study

One of the most exciting aspects of this work is what it makes possible in the future. Researchers can now begin asking questions that were previously out of reach, such as how membrane thickness changes over time, how proteins reshape membranes as they move, and how cellular states influence membrane architecture.

By combining high-resolution imaging with computational analysis, the Surface Morphometrics approach provides a new lens for studying cellular organization in its natural context. It shifts membrane research from simplified models to the complexity of real biology.

Research paper reference

Surface Morphometrics reveals local membrane thickness variation in organellar subcompartments, Journal of Cell Biology (2025).

https://rupress.org/jcb/article/225/3/e202505059