Piercing Pathogens With Nanospikes Is Emerging as a Powerful New Anti-Biofilm Strategy

Bacteria love surfaces. Give them a catheter, a food-processing pipe, or a medical implant, and many species will happily settle in, multiply, and form biofilms—sticky, protective communities that are notoriously difficult to remove. Biofilms are a major cause of hospital-acquired infections and industrial contamination, and once they form, they can be extremely resistant to antibiotics and disinfectants.

Now, researchers are exploring a very different way to stop these microbial squatters. Instead of poisoning bacteria or repelling them with chemicals, scientists are developing surfaces that physically kill microbes on contact. The idea is surprisingly simple: if bacteria land on a surface covered in nanoscale spikes or pillars, their membranes stretch, tear, and rupture. No drugs, no toxins—just physics.

Why Biofilms Are Such a Persistent Problem

Biofilms form when bacteria attach to a surface and secrete a glue-like matrix that protects them from environmental threats. Inside this matrix, bacteria can be up to a thousand times more resistant to antibiotics than free-floating cells. This makes biofilms especially dangerous in healthcare settings, where they commonly form on catheters, implants, and surgical tools.

Traditional strategies to combat biofilms often rely on chemical coatings, such as antimicrobials, silver, or other heavy metals. While these approaches can work, they come with serious drawbacks. Chemical agents can lose effectiveness over time, leach into surrounding environments, contribute to antimicrobial resistance, or raise toxicity concerns.

These limitations have pushed researchers to ask a bold question: what if surfaces could kill bacteria without using chemistry at all?

A Physical Solution Inspired by Nature

The inspiration for this idea came from an unexpected place: insect wings. More than a decade ago, researchers studying superhydrophobic surfaces—those that strongly repel water—noticed something unusual when bacteria were placed on cicada wings. The bacteria stuck to the wings, but they quickly became deformed and died.

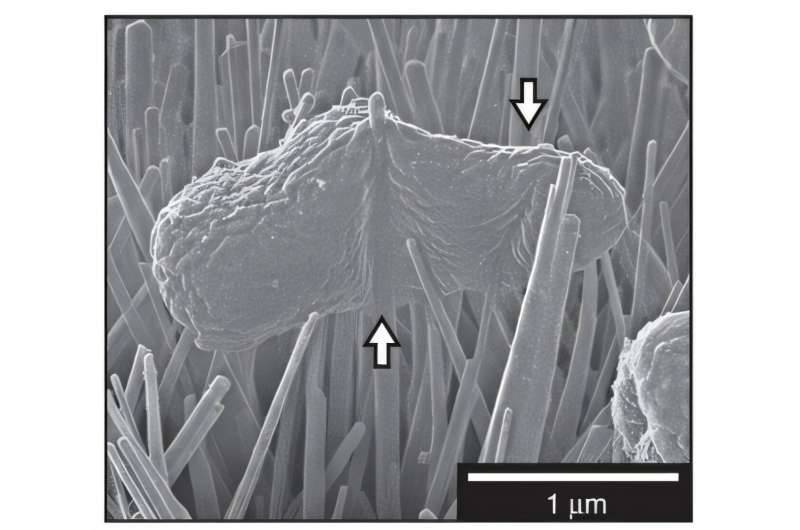

Closer examination revealed why. Cicada wings are covered in nanopillars, tiny protrusions spaced just far enough apart that bacterial cells sag between them. As the cell membrane stretches across these gaps, mechanical stress builds up until the membrane tears. The bacterium is essentially punctured to death.

Crucially, this killing mechanism is mechanical, not chemical. When researchers coated the wings with gold—changing their chemical composition but leaving the structure intact—the antibacterial effect remained. This showed that the physical architecture of the surface, not its chemistry, was responsible for killing the bacteria.

Similar bactericidal nanostructures have since been found on dragonfly wings and even on the skin of animals like geckos. Nature, it turns out, has been using mechanical antimicrobial defenses all along.

How Nanopatterned Surfaces Kill Bacteria

When scientists try to replicate this effect in engineered materials, they refer to the result as mechano-bactericidal surfaces. These surfaces are patterned with nanoscale features such as pillars, spikes, blades, or shards.

The exact killing mechanism can vary depending on the material and geometry:

- Membrane stretching and rupture, similar to what happens on cicada wings

- Direct impalement or slicing, seen with sharp nanostructures like graphene edges

- Stress-induced cell death, where mechanical damage triggers internal self-destruct pathways

Importantly, there is a delicate balance involved. If the nanostructures are too short, bacteria barely notice them. If they are too tall or too densely packed, the bacteria can sit on top like someone lying on a bed of nails, avoiding lethal stress. Achieving the right height, spacing, and density is critical for maximum killing efficiency.

Another challenge is that bacteria are not all built the same. Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have thinner cell walls and are often more susceptible to mechanical rupture. Gram-positive bacteria, like Staphylococcus species, have thicker walls and can be harder to kill with the same surface design.

Beyond Bacteria: Fungi and Viruses Too

Mechanical killing does not stop with bacteria. Studies have shown that nanopatterned surfaces can also damage fungi, including Candida albicans. In some cases, the mechanical stress triggers apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, preventing fungal growth and spread.

There is also evidence that certain nanostructured surfaces can inactivate viruses, including influenza, by disrupting viral envelopes or preventing stable attachment. This opens the door to broader antimicrobial applications that go far beyond traditional antibiotics.

The Manufacturing Challenge

Despite their promise, mechano-bactericidal surfaces face a major obstacle: scalability. Many nanofabrication techniques are expensive, slow, or limited to small areas.

For example, vertical graphene nanostructures are highly effective at stabbing bacteria, but they require temperatures above 700°C to grow. This makes them incompatible with many common materials, especially polymers used in medical devices and packaging. The energy demands also raise sustainability concerns.

Other fabrication methods include laser etching, chemical vapor deposition, and self-assembly processes. While effective in the lab, these techniques can be difficult to control precisely or scale up for mass production.

A Breakthrough Using Metal-Organic Frameworks

A promising new approach involves metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs. These crystalline materials are made from metal ions linked by organic molecules, forming highly tunable, porous structures. MOFs are already produced at large scales for applications like gas storage and catalysis, which makes them attractive for antimicrobial surfaces.

In recent work, researchers created MOFs with a zirconium-based core and iron-based nanospikes, resembling tiny jacks from the classic game. These MOFs can either be grown directly on a surface or drop-cast onto it, making the process far more flexible and scalable than high-temperature graphene growth.

The resulting surfaces were effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Depending on how the MOFs were applied, they killed bacteria by stretching, impaling, or injuring the cells. Drop-cast surfaces showed particularly high killing efficiency—around 83 percent—because they provided more complete coverage with nanospikes.

Tackling Long-Term Performance

One concern with any bactericidal surface is what happens after many bacteria die on it. Over time, debris could accumulate and reduce effectiveness. Some researchers believe this is less of a problem than expected, as nanoscale debris can simply wash away.

Others are experimenting with self-renewing designs. One strategy involves embedding MOFs in a biodegradable polymer. When bacteria land and die, they degrade the polymer, exposing a fresh layer of nanospikes underneath. This layered approach could provide longer-lasting protection.

Where This Technology Could Be Used

Mechano-bactericidal surfaces have enormous potential in real-world settings. Possible applications include:

- Medical devices, such as catheters, implants, and surgical tools

- Hospital surfaces, where preventing biofilm formation is critical

- Food processing and packaging, to reduce contamination

- Public infrastructure, including water systems and transportation hubs

Researchers emphasize that mechanical killing does not have to replace chemical methods entirely. Combining nanostructured surfaces with chemical agents, light-based activation, or antimicrobial coatings could lead to near-complete elimination of surface-bound microbes.

Looking Ahead

While current designs often kill 40 to 80 percent of bacteria, researchers are aiming higher. For high-risk environments, partial killing is not enough. The goal is to engineer surfaces that achieve near-total microbial elimination while remaining durable, scalable, and safe.

What makes this field especially exciting is how much remains unexplored. Nanofabrication is still a young science, and small changes in structure can lead to dramatically different outcomes. As researchers continue to refine designs and manufacturing methods, mechano-bactericidal surfaces are increasingly seen not as a niche curiosity, but as a serious new weapon in the fight against biofilms.

Research References

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16520-6

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/advs.202403456