Proteins That Help Parkinson’s Disease Spread Through the Brain Have Been Identified by Researchers

Scientists at Yale School of Medicine have identified two specific proteins on brain cells that appear to play a major role in how Parkinson’s disease pathology spreads through the brain. The discovery sheds new light on one of the biggest unanswered questions in Parkinson’s research: how a toxic protein moves from neuron to neuron and drives the gradual worsening of the disease.

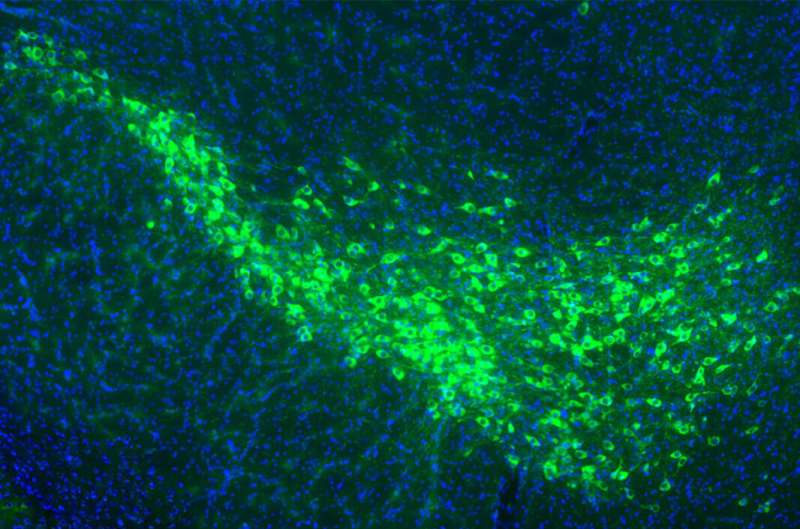

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in which certain brain cells slowly stop functioning and eventually die. The most affected cells are dopamine-producing neurons in a region called the substantia nigra, which is critical for controlling movement. As these cells are lost, people begin to experience symptoms such as tremors, stiffness, balance problems, and slowed movement.

At the center of this process is a protein called α-synuclein. In healthy brains, α-synuclein plays a role in normal communication between neurons. In Parkinson’s disease, however, the protein becomes misfolded, clumps together, and forms toxic aggregates. These aggregates are considered the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease.

What has remained unclear until now is how misfolded α-synuclein spreads from one neuron to another, gradually affecting more and more areas of the brain.

How Misfolded α-Synuclein Moves Between Neurons

Previous research has shown that misfolded α-synuclein can escape from dying neurons and somehow enter neighboring healthy ones. Once inside, it can trigger further misfolding, setting off a chain reaction that worsens the disease over time. The key mystery has been how the protein gets into new neurons in the first place.

The new Yale study, published in Nature Communications, suggests that this process is not random. Instead, it appears to rely on specific cell surface proteins that act as entry points.

To investigate this, the research team conducted a large-scale screening experiment. They created 4,400 different batches of cells, with each batch engineered to express a different cell surface protein. These cells were then exposed to misfolded α-synuclein to see whether the protein would bind to any of them.

Most surface proteins showed no interaction at all. However, 16 proteins did bind to misfolded α-synuclein, and two of these stood out because of where they are found in the brain.

The Role of mGluR4 and NPDC1

The two proteins identified as especially important were mGluR4 and NPDC1. Both are found on the surface of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, the exact cell population that degenerates in Parkinson’s disease.

Further experiments showed that these proteins do more than simply bind to misfolded α-synuclein. Together, they actively transport the toxic protein into neurons. In other words, mGluR4 and NPDC1 appear to form a molecular pathway that allows misfolded α-synuclein to cross the cell membrane and enter healthy brain cells.

This finding points to a specific mechanism by which Parkinson’s pathology spreads, rather than a vague or passive process.

Testing the Idea in Animal Models

To confirm whether these proteins truly drive disease progression, the researchers moved from cell experiments to mouse models. They genetically modified mice so that either mGluR4 or NPDC1 did not function properly. The mice were then exposed to misfolded α-synuclein.

In normal mice, the injected α-synuclein accumulated in the brain, dopamine neurons degenerated, and the animals developed Parkinson’s-like symptoms. In contrast, mice lacking functional mGluR4 or NPDC1 showed a strikingly different outcome.

In these modified mice, dopamine neurons were largely preserved, even after exposure to misfolded α-synuclein. The spread of toxic protein was reduced, disease progression slowed, and the risk of death decreased. This provided strong evidence that both proteins are required for α-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration to take place.

Taken together, the results suggest that mGluR4 and NPDC1 work as a functional complex, helping misfolded α-synuclein move from one neuron to another and drive the disease forward.

Why This Matters for Parkinson’s Treatment

Most current treatments for Parkinson’s disease focus on managing symptoms, primarily by replacing or mimicking dopamine. While these approaches can improve quality of life, they do not stop the underlying disease from progressing.

By identifying a molecular pathway that enables α-synuclein to spread, this research opens the door to a new therapeutic strategy: blocking the movement of the toxic protein itself. If scientists can develop drugs that interfere with mGluR4, NPDC1, or their interaction, it may be possible to slow or even halt disease progression, rather than just treating symptoms.

This approach could be especially important given the aging population. Parkinson’s disease primarily affects older adults, and the number of people over 65 in the United States is expected to rise significantly in the coming decades. As a result, the number of Parkinson’s cases is also projected to increase.

Currently, an estimated 1.1 million Americans are living with Parkinson’s disease, and nearly 90,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Finding ways to slow neuron loss could have a major impact on public health.

Understanding α-Synuclein Beyond Parkinson’s

α-Synuclein is not only relevant to Parkinson’s disease. Similar misfolded protein spreading is seen in other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, where abnormal tau and beta-amyloid proteins propagate through the brain.

This growing body of research suggests that neurodegenerative diseases may share common mechanisms, including protein misfolding, cell-to-cell transmission, and progressive network damage. Discoveries like the identification of mGluR4 and NPDC1 help scientists understand these shared pathways at a deeper molecular level.

Why Cell Surface Proteins Are Key Targets

Cell surface proteins are especially attractive drug targets because they are accessible from outside the cell. Unlike proteins buried deep inside neurons, surface proteins can potentially be blocked by antibodies or small molecules without needing to cross complex intracellular barriers.

mGluR4 is already known to play a role in neurotransmission, while NPDC1 has been linked to neuronal development and signaling. Understanding how these proteins interact with misfolded α-synuclein may also help researchers design safer treatments that minimize unintended effects on normal brain function.

Looking Ahead

While the findings are based on mouse models, they provide a strong foundation for future studies in humans. More research will be needed to determine whether blocking mGluR4 and NPDC1 is safe over the long term and whether similar effects are seen in human neurons.

Still, the study marks a significant step forward. By identifying how Parkinson’s pathology spreads at the molecular level, researchers are closer than ever to developing treatments that target the root cause of the disease rather than its symptoms.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67731-3