Genomics Reveals New Ways to Target a Chronic Childhood Disease Called Yaws

Mapping the genomes of the bacteria responsible for yaws, a long-neglected and debilitating childhood disease, is giving researchers fresh insight into why the infection keeps coming back—and how public health strategies might finally stop it. A large international research team has shown how genomic science can reveal hidden transmission patterns, expose treatment-resistant strains, and point to more effective ways of targeting this disease in vulnerable communities.

Yaws is a chronic infectious disease that mainly affects children living in warm, humid, and tropical regions. Caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue, it leads to painful skin ulcers and, in severe cases, damage to cartilage and bone that can result in lifelong disfigurement. Despite decades of eradication efforts and the availability of effective antibiotics, yaws continues to persist in parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific.

The new study, published in The Lancet Microbe, used genomic sequencing to investigate why yaws resurged in communities that had already undergone successful treatment campaigns. By analyzing the DNA of the bacteria itself, researchers were able to look beyond case numbers and uncover what was happening at a much deeper biological level.

Understanding Yaws and Why It Is So Hard to Eliminate

One of the biggest challenges with yaws is that many infected individuals do not show symptoms. These asymptomatic carriers can unknowingly harbor the bacteria for long periods, allowing it to re-emerge even after treatment programs appear to have worked. The bacterium can also lie dormant in the body, making it difficult to detect and fully eliminate from a community.

Yaws spreads through direct skin-to-skin contact, which makes children particularly vulnerable. Around 75 to 80 percent of people affected by yaws are under the age of 15. The disease is currently considered endemic in 15 countries, often in remote areas with limited access to healthcare.

While antibiotics—most commonly azithromycin—are effective at killing the bacterium, repeated exposure to antibiotics raises concerns about drug resistance, an issue that has become increasingly important in global public health.

The Study and Its Genomic Approach

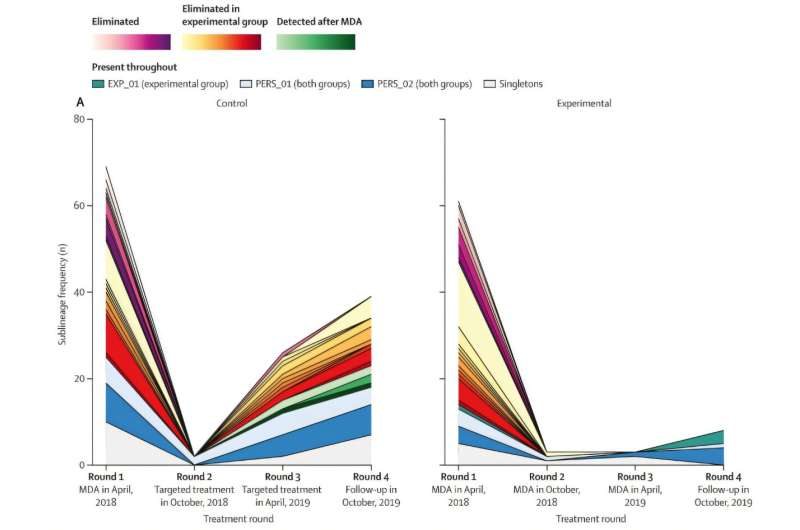

To better understand how yaws behaves after treatment, researchers examined bacterial samples from a previous clinical trial conducted in Papua New Guinea. That trial compared two intervention strategies: repeated rounds of mass drug administration, where entire communities receive antibiotics, and a strategy combining one round of mass treatment followed by targeted treatment of detected cases.

The new analysis focused on 222 bacterial genomes collected during the trial. This made it one of the most detailed genomic studies of yaws ever conducted. By comparing genomes from the beginning and end of the study, researchers could track how different bacterial strains survived, spread, or disappeared over time.

Key Findings From the Genomic Analysis

One of the most important discoveries was that yaws does not spread very far geographically. Most of the bacterial strains found toward the end of the trial were closely related to strains present at the beginning. This showed that the resurgence of yaws was caused by bacteria that had persisted locally, rather than being reintroduced from outside areas.

The data also revealed strong geographical clustering. People living closer together were more likely to share genetically similar strains of the bacterium. This suggests that yaws transmission is highly localized and closely tied to everyday contact within small communities.

Age also played a significant role. The researchers found that older school-age children were more likely to share closely related bacterial strains than younger children. This points to this age group as a key driver of transmission and suggests that targeting interventions toward older children could be especially effective in breaking the chain of infection.

Another major finding involved asymptomatic spread. The resurgence of yaws at the end of the study was likely driven by people who showed no symptoms but were still carrying and transmitting the bacteria. This highlights a critical blind spot in eradication efforts that rely only on visible symptoms.

Antibiotic Resistance and More Severe Strains

The study also uncovered worrying signs related to antibiotic resistance. One particular resistant strain of the bacterium was linked to longer-lasting skin ulcers and appeared to interfere with the body’s immune response. This marked the first time that specific genetic mutations in yaws bacteria were associated with differences in symptoms and immune reactions.

While resistant strains were relatively rare, their presence underscores the importance of genomic surveillance. Without monitoring how the bacteria evolve, resistant strains could spread unnoticed and undermine eradication efforts.

At the same time, the researchers found that repeated mass drug administration significantly reduced the genetic diversity of the bacterium. This means fewer surviving strains and a population that is closer to elimination, even if complete eradication has not yet been achieved.

What This Means for Public Health Strategies

Taken together, the findings suggest that yaws eradication efforts need to be more targeted and sustained. While mass antibiotic treatment remains an essential tool, it should be paired with strategies that account for local transmission patterns, age-specific risk, and hidden carriers.

Focusing on school-age children, closely monitoring communities after treatment, and using genomics to track resistant or persistent strains could significantly improve outcomes. The study also reinforces that yaws resurgence is not simply a failure of treatment, but often the result of bacteria surviving quietly within the community.

Why Genomics Is a Game Changer for Neglected Diseases

This research highlights the growing role of genomics in tackling neglected tropical diseases. Traditional surveillance methods can miss asymptomatic infections and subtle transmission patterns. Genomic data, on the other hand, provides a precise and objective way to see how pathogens move, change, and survive.

For yaws, a disease that humanity has been trying to eradicate for over 70 years, this level of insight could make the difference between temporary success and lasting elimination. It also offers a model for how genomics can be applied to other chronic infectious diseases that continue to resist standard public health approaches.

Looking Ahead

The study makes it clear that yaws is not an unsolvable problem, but it does require careful, informed strategies. Antibiotics work, but resistance is a real threat. Community-wide treatment helps, but without follow-up and genomic monitoring, the disease can quietly return.

By combining genomic science, targeted interventions, and sustained public health efforts, researchers believe that yaws eradication is still within reach. This study provides some of the clearest evidence yet of how to move closer to that goal.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanmic.2025.101229