Fatal Infection Risk in Newborns May Increase When This Bacterium and Fungus Mix

Researchers from the University of Maine have uncovered new evidence suggesting that a common interaction between a bacterium and a fungus may significantly raise the risk of serious, and potentially fatal, infections in newborns. Even more concerning, this interaction appears to make standard medical treatments less effective, which could have important implications for how infections are managed during pregnancy and childbirth.

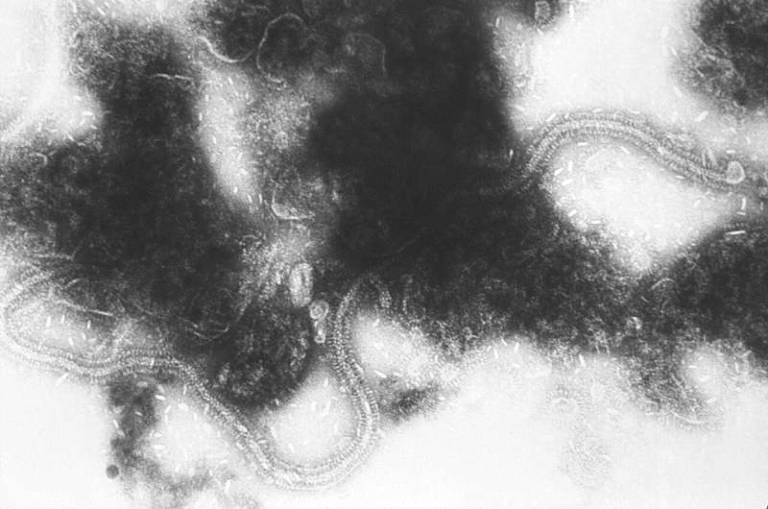

The study focuses on the interaction between Streptococcus agalactiae, more commonly known as Group B Streptococcus (GBS), and the fungal species Candida albicans, a frequent cause of yeast infections. Both microbes are widespread in the human population and are often harmless in healthy adults. However, the new findings show that when these two organisms coexist, their combined presence can make infections more aggressive and harder to control, especially in vulnerable populations like newborn babies.

Understanding Group B Strep and Why It Matters

GBS is a bacterium carried by about one-fifth of healthy people worldwide. In most cases, it lives quietly in the gastrointestinal or reproductive tract without causing symptoms. Problems arise when GBS infects individuals with weakened immune systems, including pregnant women, newborns, and older adults.

In newborns, GBS exposure can occur in utero or during childbirth, leading to severe infections such as sepsis or meningitis. GBS-related meningitis is particularly dangerous, as it can be fatal or leave survivors with lifelong neurological complications. For this reason, many countries have adopted screening programs to detect GBS in pregnant women late in pregnancy and provide intravenous antibiotics during labor if needed.

Candida Albicans and Its Overlooked Role

Candida albicans is a fungus that naturally lives in many parts of the body, including the mouth, gut, and genital tract. While it often causes no harm, it can lead to yeast infections when conditions allow it to overgrow. Nearly one-third of women worldwide carry some level of C. albicans in their genital tract.

Importantly, GBS and C. albicans are frequently found in the same environments within the body. GBS is present in roughly 10–30% of pregnant women, meaning co-colonization with C. albicans is not uncommon. Previous research has already shown that these two microbes are often associated with one another in clinical settings, but until now, little was known about how they directly influence each other’s behavior during infection.

What the New Study Found

To explore this interaction, researchers grew GBS and C. albicans together in laboratory cultures and compared them to cultures where each organism was grown separately. The results were striking. GBS cells grew faster and more robustly when they shared the same environment as C. albicans.

One surprising discovery was that the two organisms did not need to physically interact for this effect to occur. Even when separated, the presence of C. albicans was enough to enhance GBS growth. This suggests that the fungus may alter the surrounding environment in ways that benefit the bacterium, possibly by changing nutrient availability or releasing growth-promoting factors.

Testing Virulence in a Living Model

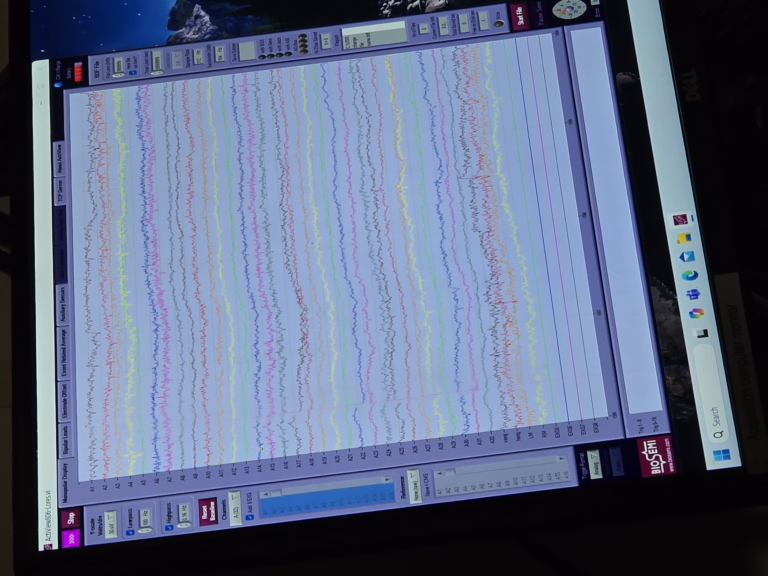

The researchers went a step further by examining how these interactions affect real infections. They used zebrafish larvae, a well-established model in biomedical research. Zebrafish share important genetic similarities with humans and have transparent bodies at early life stages, allowing scientists to observe infections in real time.

When GBS and C. albicans were injected together into zebrafish larvae, the bacteria became more infectious and more deadly compared to GBS alone. The bacterial load increased, and the infections progressed more aggressively. This confirmed that the interaction seen in the lab also has real consequences in living organisms.

However, the effects were environment-dependent. When the microbes were introduced into different parts of the zebrafish, such as the yolk sac versus the otic vesicle, the severity of infection varied. This suggests that factors like local nutrients, tissue type, and gene expression play an important role in how these microbes influence one another.

Reduced Effectiveness of Antibiotics

One of the most concerning findings involved antibiotic resistance. When GBS was exposed to C. albicans, standard antibiotic treatments were less effective. In particular, the antibiotic clindamycin, sometimes used in patients who cannot tolerate first-line treatments, was less successful at preventing death in co-infected zebrafish.

This finding raises important clinical questions. Currently, the standard approach for preventing newborn GBS infection is to administer intravenous antibiotics to GBS-positive pregnant women several hours before delivery. The new research suggests that if C. albicans is also present, these antibiotics may not fully clear the bacteria, potentially leaving newborns at greater risk.

Why Nutrients and Environment Matter

The researchers also observed that nutrient availability plays a key role in shaping how GBS and C. albicans interact. Levels of sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients influenced microbial growth patterns and antibiotic response. These environmental factors likely affect gene expression in both organisms, altering their behavior and their ability to resist treatment.

This insight helps explain why co-infections can behave differently depending on where they occur in the body and under what conditions. It also highlights why treating infections is rarely a one-size-fits-all process.

Implications for Pregnancy and Newborn Care

The findings raise an important concern for clinicians: whether pregnant women carrying both GBS and C. albicans are at higher risk of transmitting more dangerous infections to their babies. While current screening focuses primarily on GBS, the researchers suggest that identifying co-infections may provide valuable information when making treatment decisions.

At this stage, the research does not call for immediate changes to medical guidelines. Instead, it opens the door to future studies that could determine whether additional screening or adjusted treatment strategies are warranted in certain cases.

Why Zebrafish Are Central to This Research

This study also highlights the growing importance of zebrafish models in medical research. The University of Maine recently expanded its zebrafish laboratory, which supports studies on infections, cancer, toxins, muscular dystrophy, and other human health challenges. Zebrafish offer a unique balance between simplicity and biological relevance, making them ideal for studying complex interactions like polymicrobial infections.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that more work is needed to determine how these findings translate to real-world clinical outcomes. Key questions include whether co-colonized individuals truly face higher risks and how treatment protocols might be optimized to address mixed infections.

What is clear, however, is that interactions between microbes matter. This study reinforces the idea that infections are often multispecies events, and understanding how bacteria and fungi influence each other may be essential for improving patient care, especially for the most vulnerable patients.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00528-25