Pain-Sensing Neurons Kick-Start Immune Responses That Drive Allergies and Asthma

Pain-sensing neurons are best known for alerting us to danger, discomfort, and injury. But new research shows they are doing far more than just sending pain signals to the brain. A study from Weill Cornell Medicine reveals that these neurons can actively initiate immune responses that play a major role in allergies and asthma. The findings challenge long-standing assumptions in immunology and suggest that the nervous system is a key driver of inflammatory disease, not just a passive bystander.

The study, published in Nature, focuses on a specific group of sensory neurons called nociceptors. These neurons are widely distributed throughout the body, including the gut, and are responsible for detecting irritating or harmful stimuli such as heat, chemical compounds, and mechanical stress. According to the researchers, nociceptors in the intestine are capable of sensing threats and directly triggering immune reactions that resemble those seen in allergic diseases.

A New Way of Thinking About Allergies and Asthma

Most current treatments for allergies and asthma focus almost entirely on the immune system. Biologic drugs target immune molecules involved in inflammation, such as cytokines and antibodies. However, these treatments are often only partially effective, and their benefits can fade over time. This study helps explain why.

The researchers found that immune cells are not acting alone. Instead, pain-sensing neurons are among the earliest responders, setting the immune response in motion. By overlooking neurons, existing therapies may be addressing only part of the problem.

This idea has been developing for years. Many hallmark symptoms of allergies and asthma — including itching, wheezing, coughing, and gut cramping — are tightly controlled by neurons. That connection prompted the research team to explore whether sensory neurons might also be involved at a deeper, biological level.

Using Parasitic Infection to Study Immune Activation

To investigate this possibility, the researchers turned to a well-established model of type 2 immune responses, the same category of immune activity that drives allergies and asthma. This type of response also plays a critical role in defending the body against parasitic worms.

In the study, mice were infected with Trichuris muris, a parasitic intestinal worm. This infection reliably triggers a strong type 2 immune reaction, making it an ideal system for studying how immune defenses are launched.

The team closely monitored nociceptors in the gut during infection. These neurons are equipped with specialized endings that detect irritating compounds, including substances like capsaicin, the chemical responsible for the heat of chili peppers. This sensory ability makes nociceptors well suited to detect parasites and allergens alike.

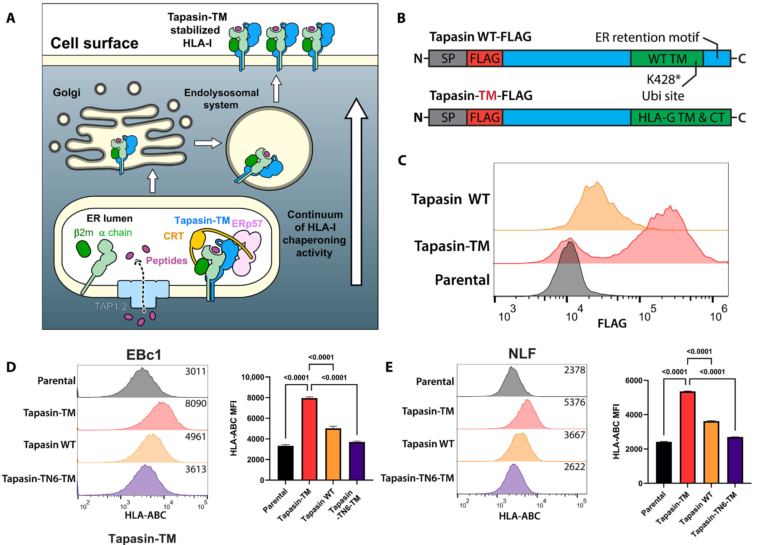

The results showed that Trichuris muris directly activated nociceptors. Once activated, these neurons released a signaling molecule called CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide). This molecule turned out to be a critical messenger between the nervous system and the immune system.

The Central Role of Tuft Cells

CGRP released by nociceptors did not act on immune cells directly. Instead, it targeted a rare and unusual type of epithelial cell lining the intestine known as tuft cells.

Tuft cells are not classical immune cells, but they play a crucial role in immune defense, especially against parasites. These cells have distinctive finger-like projections that extend into the intestinal lumen, allowing them to sense changes in the gut environment.

When stimulated by neuronal signals, tuft cells release molecules that activate downstream immune pathways responsible for parasite clearance. In this study, the partnership between nociceptors and tuft cells proved to be especially powerful.

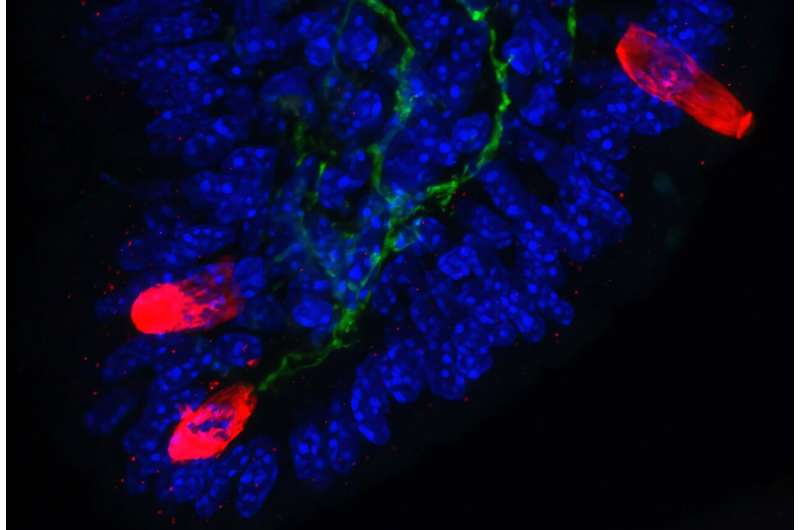

The researchers observed that neuronal activation led to a rapid and dramatic expansion of tuft cells. Using immunofluorescence microscopy, they found that within just 24 hours, tuft cell numbers increased nearly fivefold. This expansion reshaped the intestinal lining, creating an environment primed for a fast and effective immune response.

In addition to activating existing tuft cells, nociceptors released chemical signals that caused other epithelial cells to transform into new tuft cells. This process further amplified the immune response and prepared the gut for future threats.

What Happens When Neurons Are Silenced

To confirm the importance of nociceptors, the researchers also examined what happens when these neurons are removed or silenced. In these cases, tuft cell numbers dropped significantly, and the intestine struggled to fight off the parasitic infection.

This finding reinforced the idea that nociceptors are not optional contributors. They are essential for launching and sustaining effective type 2 immune responses in the gut.

When Protective Responses Become Harmful

While this neuro-immune partnership is beneficial in the context of parasitic infection, it comes with a downside. Type 2 immune responses are powerful, and when they become excessive or chronic, they can lead to disease.

The same pathways that help eliminate parasites can also drive allergic inflammation, asthma, and tissue fibrosis. The researchers believe that similar neuron-driven mechanisms may operate in the lungs, skin, and other barrier tissues.

This could explain why allergic diseases often involve both immune dysfunction and sensory symptoms. It may also clarify why some reactions begin with sensations such as abdominal cramping or discomfort before measurable immune activation is detected.

A Shift in Immunology

Traditionally, scientists believed that type 2 immune responses were initiated through coordinated interactions between epithelial cells and immune cells. This study adds a new and unexpected player to that model: the nervous system.

By demonstrating that nociceptors can kick-start immune reactions, the research introduces a textbook-changing concept. Sensory neurons are not just responding to inflammation; they are actively shaping it from the very beginning.

Implications for Future Treatments

If the same neuron-immune interactions observed in mice also exist in humans, the implications for treatment are significant. Therapies that target only immune pathways may never fully control allergic disease if neuronal signals continue to drive inflammation.

Future treatments could aim to modulate both the immune system and the nervous system, potentially leading to more durable and effective control of allergies and asthma. Researchers are already considering examining patient biopsy samples to look for evidence of nociceptor and tuft cell activation in human tissues.

The Growing Field of Neuro-Immune Research

This study is part of a broader scientific movement exploring how nerves and immune cells communicate. Researchers now know that barrier tissues such as the gut, lungs, and skin are densely populated with sensory neurons that interact closely with immune cells.

Neuropeptides like CGRP, substance P, and others are increasingly recognized as powerful immune modulators. Understanding these interactions could reshape how inflammatory diseases are diagnosed and treated across multiple medical fields.

As this research shows, pain-sensing neurons are not merely messengers of discomfort. They are active decision-makers, capable of triggering immune defenses that protect the body — or, when unchecked, contribute to disease.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09921-z