Want to Speed Brain Research It All Depends on How Smart Microscopes Look at the Brain

Want to map the brain faster without spending millions on rare equipment? A new research effort from scientists at Harvard and MIT suggests the answer lies not in building bigger microscopes, but in making existing ones smarter. Their newly developed system, called SmartEM, uses machine learning to dramatically accelerate brain imaging while preserving the extreme detail required for modern neuroscience.

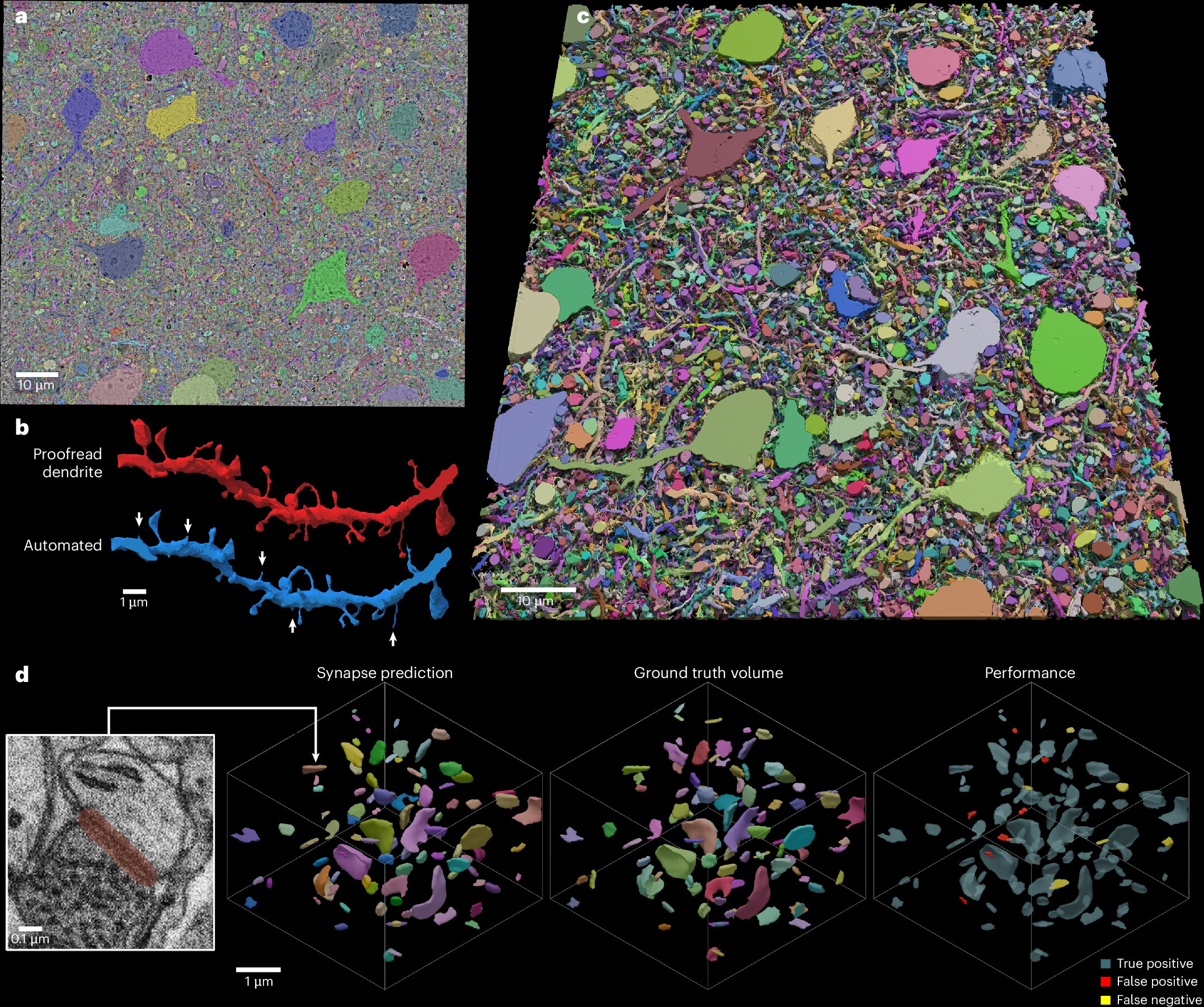

At its core, SmartEM changes how electron microscopes collect data. Instead of scanning every pixel of brain tissue with the same level of intensity and time, the system selectively focuses on the most important regions—much like human vision, which naturally zooms in on meaningful details and ignores empty background. This shift in strategy could reshape the field of connectomics, the science of mapping neural connections at nanometer-scale resolution.

Why Brain Mapping Has Been So Slow

Creating detailed brain maps, also known as connectomes, is one of the most technically demanding tasks in science. Researchers aim to reconstruct neurons, synapses, blood vessels, and cellular structures at scales measured in billionths of a meter. To do this, they rely on serial-section electron microscopy, a method that involves slicing brain tissue into thousands of ultra-thin sections and scanning each slice individually.

As an example, a landmark Harvard study published recently mapped just 1 cubic millimeter of human brain tissue. That poppy-seed-sized sample contained 150 million synapses, 57,000 cells, and 230 millimeters of blood vessels. Producing this dataset required more than 5,000 sections, each thinner than one-thousandth the width of a human hair, and generated an enormous volume of imaging data.

The biggest bottleneck has been speed and cost. High-throughput multibeam electron microscopes—some equipped with up to 91 beams—can scan tissue faster, but they cost millions of dollars and are available only at a handful of elite institutions. As a result, connectomics has remained a specialized field with limited global participation.

What SmartEM Does Differently

SmartEM is designed to work with single-beam scanning electron microscopes, which are far more common in research labs worldwide. The key innovation is how scanning time, known as dwell time, is allocated.

Traditionally, microscopes spend the same amount of time on every pixel, regardless of whether that pixel contains a critical synapse or an empty region of tissue. SmartEM replaces this uniform approach with a machine learning–guided workflow:

- The microscope first performs a fast, low-quality scan of the entire sample.

- A neural network analyzes this initial scan in real time to identify regions that contain important biological structures or areas prone to imaging errors.

- Only those selected regions are rescanned at higher resolution with longer dwell times.

- An algorithm then blends the low- and high-resolution data into a single uniform-looking image suitable for analysis.

The result is a dataset that is scientifically equivalent to a full high-resolution scan but produced in a fraction of the time.

Proven Speed Gains Across Species

The SmartEM system was tested on brain tissue samples from worms, mice, and humans, demonstrating consistent performance improvements. One striking example involved Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm species that became famous decades ago as the first organism to have its full wiring diagram mapped.

Using conventional methods, imaging the worm’s brain and body with a single-beam microscope would take approximately 1,400 hours. With SmartEM, the same task was completed in just 200 hours, a roughly sevenfold increase in speed. Importantly, the final reconstructed wiring diagram was indistinguishable from one produced using slower traditional scans.

Similar gains were observed in mouse cortex samples, where SmartEM enabled rapid reconstruction of neurons and synapses without sacrificing accuracy.

Making Connectomics More Accessible

One of the most significant implications of SmartEM is its potential to democratize connectomics. Rather than relying on rare, ultra-expensive multibeam machines, many institutions could upgrade their existing single-beam microscopes with SmartEM software and machine learning integration.

This shift could allow many more research groups to contribute to brain-mapping efforts across species, accelerating progress toward major goals like a complete mouse connectome, which is widely considered the next grand challenge in neuroscience.

In December, Nature Methods recognized the importance of these advances by naming electron microscopy–based connectomics its Method of the Year for 2025, explicitly citing SmartEM as a standout innovation.

How Human Vision Inspired the Technology

The design philosophy behind SmartEM borrows heavily from how human eyes and brains process visual information. When we look at a page of text, we do not examine every square millimeter equally. Instead, our eyes rapidly scan the page, then focus attention on letters and words while ignoring blank margins.

SmartEM applies this same principle to microscopy. By allowing the machine learning system to decide where to “look harder,” the microscope avoids wasting time on regions that provide little useful information.

A Large Collaborative Effort

SmartEM is the result of a five-year collaboration involving researchers from Harvard University, MIT, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and Thermo Fisher Scientific, one of the world’s leading microscope manufacturers. This combination of academic neuroscience, machine learning expertise, and industrial hardware development was essential to making the system work in real-world laboratory conditions.

The research team emphasizes that SmartEM is not a finished product but a foundation. With further improvements in algorithms and hardware integration, they believe single-beam microscopes could eventually rival today’s fastest multibeam systems.

Why Connectomics Matters

Connectomics aims to reveal how brain structure underlies behavior and cognition. By mapping how neurons connect and communicate, scientists hope to better understand learning, memory, development, and neurological disorders.

So far, complete connectomes exist for a handful of organisms, including worms, fruit flies, and zebrafish. Scaling these efforts to mammals—and eventually humans—requires not only better data analysis tools but also faster and more accessible imaging methods. SmartEM addresses one of the most critical technical barriers in this process.

Beyond Neuroscience

While SmartEM was developed with brain research in mind, its core idea—adaptive, attention-based imaging—could extend to other fields. Cell biology, pathology, and materials science often involve samples where important features are sparse. In these cases, selectively focusing imaging resources could significantly reduce time and cost.

Looking Ahead

SmartEM represents a shift in how scientists think about microscopy. Instead of pushing hardware to its limits everywhere at once, the system shows that intelligence and selectivity can deliver equally powerful results. If widely adopted, this approach could transform connectomics from a rare, resource-heavy endeavor into a more routine tool for exploring how brains are built.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41592-025-02929-3