Common Brain Parasite Can Infect Your Immune Cells and Why Scientists Say That’s Probably Not a Problem

A parasite that quietly lives in the brains of millions of people around the world has revealed yet another surprising trick. New research from the University of Virginia shows that Toxoplasma gondii, a common brain parasite, can infect CD8+ T cells, the very immune cells designed to destroy it. At first glance, this sounds alarming. But the same study explains why this unusual interaction may actually help keep the parasite under control rather than make things worse.

This research adds an important piece to the puzzle of how the human immune system manages to coexist with a parasite that infects roughly one-third of the global population, often without causing any symptoms at all.

What Is Toxoplasma gondii?

Toxoplasma gondii is a microscopic parasite that infects warm-blooded animals, including humans. People typically become infected through exposure to cat feces, contaminated soil, unwashed fruits and vegetables, or by eating undercooked meat. Once inside the body, the parasite spreads through various tissues and eventually settles into a long-term, dormant state—most notably in the brain.

For most healthy individuals, this lifelong infection goes unnoticed. However, the parasite can cause a disease called toxoplasmosis, which can be dangerous or even fatal for people with weakened immune systems, such as those undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, or individuals living with HIV. It can also pose serious risks during pregnancy.

A Surprising Discovery Inside Immune Cells

Researchers led by Tajie Harris, Ph.D., director of the Center for Brain Immunology and Glia (BIG Center) at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, set out to better understand how the immune system controls this parasite during chronic brain infection.

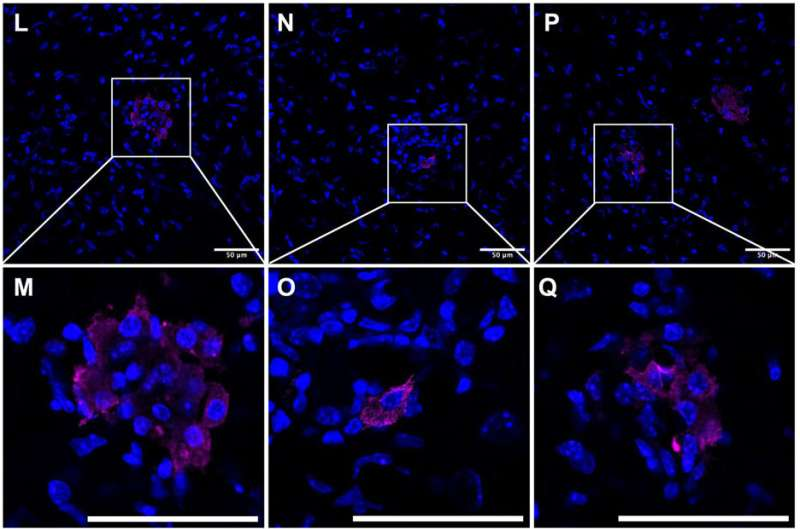

CD8+ T cells are known to be critical defenders against T. gondii. They kill infected cells directly and release signals that help other immune cells attack the parasite. What scientists did not expect to find was that T. gondii can actually infect these CD8+ T cells themselves.

This raised an obvious concern: if the parasite can hide inside immune cells, could that allow it to escape destruction and spread more easily? The answer, it turns out, is mostly no—and the reason lies in a powerful molecular safeguard within the T cells.

The Role of Caspase-8

The key player in this newly discovered defense mechanism is an enzyme called caspase-8. Caspase-8 is a well-known regulator of immune responses and is especially important for triggering programmed cell death, a controlled process that allows cells to self-destruct when they become damaged or dangerous.

The UVA researchers found that when CD8+ T cells become infected with T. gondii, caspase-8 can push those cells to die on purpose. This is a major problem for the parasite, because T. gondii can only survive and replicate inside living host cells. When the infected T cell dies, the parasite’s attempt to hijack it ends abruptly.

In other words, the immune cell sacrifices itself to eliminate the parasite hiding inside it.

What Happens When Caspase-8 Is Missing?

To understand how important this process is, the researchers studied laboratory mice that were genetically engineered to lack caspase-8 specifically in their T cells. These mice were compared to normal mice with fully functioning caspase-8.

Both groups mounted strong immune responses against the parasite. However, the differences in outcome were dramatic. Mice without caspase-8 in their T cells had far higher numbers of parasites in their brains. Over time, these mice became severely ill and ultimately died.

In contrast, mice with intact caspase-8 survived and continued living normally, even with chronic brain infection. When scientists examined the brains of the mice that died, they found that their CD8+ T cells were far more likely to be infected with T. gondii, suggesting that the inability to trigger T cell death allowed the parasite to persist and multiply.

This clearly demonstrated that caspase-8 is essential for controlling T. gondii within T cells and protecting the brain during long-term infection.

Why This Finding Is Unusual

Pathogens that infect T cells are surprisingly rare. While many viruses and parasites infect other types of cells, few are known to survive inside CD8+ T cells. The research team reviewed existing scientific literature and found very few documented examples.

This study offers a compelling explanation. Caspase-8 acts as a built-in kill switch. Any pathogen that tries to live inside a CD8+ T cell risks being destroyed when the host cell self-destructs. Only pathogens that can somehow interfere with caspase-8 would have a chance of surviving—and T. gondii does not appear to have that ability.

Why Most People Never Get Sick

This research helps explain one of the biggest mysteries surrounding toxoplasmosis: why so many people carry the parasite without ever developing symptoms.

In healthy individuals, multiple layers of immune defense keep the parasite in check. CD8+ T cells are a crucial part of this defense, and caspase-8 ensures that even when these cells become infected, they do not turn into safe havens for the parasite.

For people with compromised immune systems, this balance can break down. If immune responses weaken or critical pathways like caspase-8 are disrupted, T. gondii can gain the upper hand, leading to uncontrolled infection and serious neurological disease.

Broader Implications for Immunology

Beyond toxoplasmosis, this study highlights the broader importance of caspase-8 in immune protection. The enzyme is now recognized as a key factor not just in cell death, but in limiting how pathogens interact with immune cells themselves.

Understanding how caspase-8 functions could eventually help researchers develop new therapies for infections that target immune cells or for conditions where immune responses become dysregulated.

About the Research Team

The study was conducted by a team of scientists from the University of Virginia, including Lydia A. Sibley, Maureen N. Cowan, Abigail G. Kelly, NaaDedee A. Amadi, Isaac W. Babcock, Sydney A. Labuzan, Michael A. Kovacs, Samantha J. Batista, John R. Lukens, and Tajie Harris. The researchers reported no financial conflicts of interest related to the work.

Their findings were published in Science Advances, a peer-reviewed scientific journal.