Researchers Uncover Molecular Roots of Tissue Scarring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Researchers are getting closer to understanding why long-term inflammation can permanently damage tissues, especially in people living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A new study published in Nature reveals how specific cells in the gut communicate during chronic inflammation and identifies a previously underappreciated molecular regulator that drives fibrosis, or tissue scarring. This discovery could eventually open the door to treatments that directly target fibrosis—something current therapies largely fail to do.

Fibrosis is a serious and often irreversible consequence of chronic inflammation. When the immune system remains active for too long, it can trigger excessive tissue repair responses, leading to thickened, stiff, scarred tissue. In the gut, this process can narrow the intestines, disrupt normal function, and ultimately result in organ failure or the need for surgery. Fibrosis is a major complication not only in IBD—which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—but also in lung disease, chronic viral infections, heart disease, and autoimmune skin disorders such as scleroderma.

Despite its impact, fibrosis has remained difficult to treat. Most available therapies focus on suppressing inflammation, not stopping or reversing the scarring that inflammation leaves behind. The new research addresses this gap by mapping the molecular and cellular circuitry that drives fibrosis in IBD.

A Closer Look at Fibrosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The study builds on earlier work by researchers at the Broad Institute and Mass General Brigham, who previously identified a unique cell type involved in intestinal scarring. This cell, known as an inflammation-associated fibroblast, plays a central role in laying down scar tissue in the gut. Until now, however, scientists did not fully understand how these fibroblasts were activated or how they interacted with other cells in inflamed tissue.

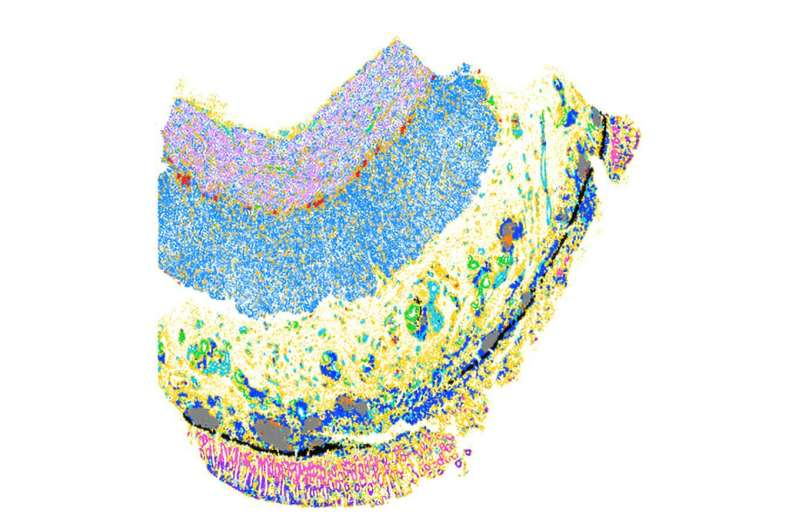

Using a combination of single-cell sequencing and spatial mapping techniques, the researchers analyzed intestinal tissue samples from patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These methods allowed them to identify individual cells, determine what genes those cells were expressing, and see exactly where the cells were located within the tissue.

This approach revealed that inflammation-associated fibroblasts consistently appeared near inflammatory macrophages, a type of immune cell involved in sustaining chronic inflammation. The physical proximity of these cells suggested an active communication loop—and further analysis confirmed that this cellular crosstalk is a key driver of fibrosis.

How Immune Cells and Fibroblasts Drive Scarring

The researchers found that inflammatory macrophages release signaling molecules, specifically TGF-beta and IL-1, which stimulate nearby fibroblasts. In response, the fibroblasts produce IL-11, a protein known to promote tissue remodeling and scar formation.

IL-11 has been increasingly recognized as a pro-fibrotic molecule in several organs, but its precise role in IBD had not been fully characterized. In this study, IL-11 production emerged as a defining feature of inflammation-associated fibroblasts in diseased intestinal tissue.

This back-and-forth signaling between macrophages and fibroblasts creates a self-reinforcing loop: inflammation activates fibroblasts, fibroblasts deposit scar tissue, and the altered tissue environment further sustains inflammation. Breaking this loop is essential if fibrosis is to be prevented or reduced.

GLIS3 Emerges as a Master Regulator

One of the most important findings of the study is the identification of GLIS3, a transcription factor that controls how fibroblasts respond to inflammatory signals. GLIS3 was previously known for its roles in insulin production and thyroid hormone regulation, but it had not been linked to inflammatory bowel disease or fibrosis.

To uncover GLIS3’s role, the research team used CRISPR-based genetic screening to systematically test which genes are required for fibroblasts to produce IL-11. GLIS3 stood out as a master regulator of this process. Without GLIS3, fibroblasts failed to activate the fibrotic program, even in the presence of inflammatory signals.

Further experiments showed that animals lacking GLIS3 did not develop fibrosis following bowel inflammation. In human patients, higher GLIS3 activity was associated with more severe disease, strengthening the evidence that this molecule plays a central role in driving scarring.

Why This Discovery Matters for Patients

One of the most striking aspects of this research is its potential clinical relevance. There are currently no therapies specifically approved to treat fibrosis in IBD. Even when inflammation is well controlled, scarring can continue to progress, leading to long-term complications.

By identifying a specific cellular pathway—and a key molecular switch within that pathway—the study offers several possible intervention points. Targeting GLIS3, blocking IL-11, or disrupting the macrophage-fibroblast signaling loop could help prevent fibrosis from developing in the first place.

Importantly, some IL-11-neutralizing drugs are already in clinical development for other conditions. These therapies could potentially be adapted for IBD, either alone or in combination with existing anti-inflammatory treatments. This raises the possibility of treating both inflammation and its long-term consequences at the same time.

Fibrosis Beyond the Gut

While this study focused on inflammatory bowel disease, its implications extend far beyond the intestine. Fibrosis is a common feature of many chronic inflammatory conditions, including interstitial lung disease, heart disease, and autoimmune disorders.

The researchers believe that the GLIS3-dependent pathway they identified may operate in other tissues as well. Ongoing work aims to explore how GLIS3 is regulated and whether similar fibroblast-immune cell interactions drive scarring in other organs.

If confirmed, this could lead to a broader class of anti-fibrotic therapies applicable across multiple diseases—a long-standing goal in medicine.

Understanding Fibroblasts and Chronic Inflammation

Fibroblasts were once thought to be passive structural cells, responsible only for producing connective tissue. Over the past decade, however, scientists have learned that fibroblasts are highly dynamic and diverse, with specialized subtypes that actively shape immune responses.

In chronic inflammatory diseases like IBD, fibroblasts do much more than repair damage. They respond to immune signals, secrete cytokines, and remodel tissue architecture in ways that can either support healing or drive pathology. The identification of inflammation-associated fibroblasts highlights how important these cells are in determining disease outcomes.

Understanding fibroblast behavior is now seen as essential for developing next-generation therapies that go beyond immune suppression and address the structural damage caused by long-term inflammation.

What Comes Next

Researchers at the Broad Institute and Mass General Brigham are continuing to investigate how GLIS3 functions in different disease contexts and how it might be safely targeted. While any new therapy will require extensive testing, this study provides a clear molecular roadmap for tackling fibrosis—an area where progress has been frustratingly slow.

By decoding the cellular conversations that lead to tissue scarring, scientists are laying the groundwork for treatments that could significantly improve quality of life for patients with IBD and other chronic inflammatory diseases.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09907-x