Tumor Bacteria May Be a Hidden Reason Immunotherapy Fails in Head and Neck Cancer

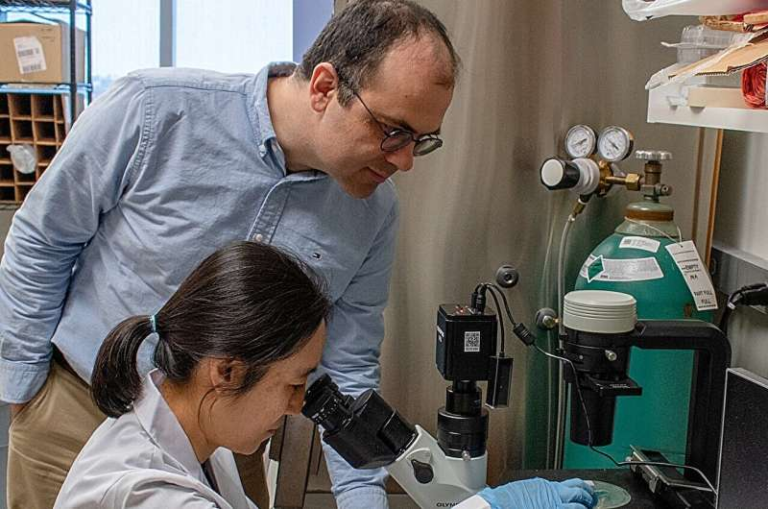

Researchers are uncovering an unexpected reason why immunotherapy does not work for many patients with head and neck cancer, and the answer may be hiding inside the tumors themselves. New studies from Cleveland Clinic scientists suggest that bacteria living within cancerous tumors play a major role in suppressing the immune system and driving resistance to immunotherapy, a treatment that has otherwise transformed cancer care for some patients.

The findings come from two major studies published simultaneously in Nature Cancer in 2025, both focused on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Together, the studies shift attention away from tumor genetics alone and toward a less explored but increasingly important factor: the tumor microbiome.

Immunotherapy Works for Some, But Not Most

Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors that target pathways like PD-1 and PD-L1, has become a promising treatment option for head and neck cancer. These drugs work by reactivating the immune system so it can recognize and attack cancer cells.

However, despite its promise, the majority of patients with head and neck cancer do not respond to immunotherapy. Until now, most research has focused on tumor mutations, PD-L1 expression, and other genetic or molecular markers to explain this resistance. The new Cleveland Clinic research suggests that bacteria inside tumors may be just as important, if not more so.

High Levels of Tumor Bacteria Suppress Immune Response

The first study analyzed genetic and molecular data from patient tumor samples. Instead of focusing on which bacterial species were present, researchers looked at overall bacterial abundance inside tumors, also known as tumor bacterial burden.

What they found was striking. Tumors with higher levels of bacteria showed weaker immune responses, regardless of the specific bacterial strains involved. This means that it is not a single “bad” bacterium causing the problem, but rather the total amount of bacteria within the tumor environment.

These bacteria-rich tumors were far less responsive to immunotherapy, suggesting that bacterial load itself is a major driver of treatment resistance.

Antibiotics Changed Tumor Behavior in Preclinical Models

To confirm these findings, the research team tested their observations in preclinical models. When antibiotics were used to reduce bacterial levels inside tumors, tumor growth slowed and immune activity improved. In contrast, when bacteria were deliberately added back into tumors, those tumors became resistant to immunotherapy.

This experimental evidence reinforced the idea that bacteria are not just innocent bystanders. Instead, they actively shape the tumor environment in ways that prevent immunotherapy from working as intended.

Neutrophils: Helpful Cells That Backfire in Cancer

One of the most important discoveries from the studies involves neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. Normally, neutrophils are essential for fighting bacterial infections. But in the context of cancer, their role becomes more complicated.

The researchers found that tumors with high bacterial levels attracted large numbers of neutrophils. While this makes sense from an infection-fighting perspective, these neutrophils ended up suppressing the immune responses needed for immunotherapy to succeed.

Instead of helping immune cells attack cancer, neutrophils in these bacteria-rich tumors created an immunosuppressive environment, blocking the activity of key anti-cancer immune cells like cytotoxic T cells.

Evidence from a Large Phase III Clinical Trial

The second study took these findings a step further by analyzing data from the Javelin HN100 Phase III clinical trial. This large trial tested whether adding an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy drug, avelumab, to standard chemoradiotherapy could improve outcomes for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

The results were revealing. Patients whose tumors had high bacterial levels experienced worse outcomes when immunotherapy was added, compared to patients who received standard chemoradiotherapy alone. In other words, for patients with bacteria-heavy tumors, immunotherapy did not just fail to help—it may have actually been less effective than traditional treatment.

This analysis involved collaboration between Cleveland Clinic, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, adding significant weight to the findings.

A New Biomarker for Patient Selection

One of the most important implications of this research is the potential use of tumor bacterial burden as a biomarker. Current methods for predicting immunotherapy response, such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden, often fail to identify which patients will truly benefit.

Measuring bacterial levels inside tumors could help doctors identify patients most likely to respond to immunotherapy, while sparing others from unnecessary side effects and ineffective treatment. This represents a major step toward more personalized cancer therapy.

Clinical Trials Are Already Underway

Building on these discoveries, Cleveland Clinic researchers have launched a new clinical trial to test whether targeted antibiotic treatment can reduce tumor bacterial levels and improve immunotherapy response in patients with head and neck cancer.

The goal is not to eliminate bacteria indiscriminately, but to strategically modify the tumor microbiome in a way that restores immune function and enhances treatment effectiveness.

Meanwhile, further research is exploring why some tumors accumulate more bacteria than others, how bacteria interact with cancer cells at a molecular level, and whether bacteria can even contribute to DNA mutations within tumors.

Why the Tumor Microbiome Matters More Than Ever

For years, cancer research focused almost entirely on cancer cells themselves. More recently, attention has expanded to include the tumor microenvironment, which includes immune cells, blood vessels, signaling molecules, and now, bacteria.

These studies make it clear that tumors are ecosystems, not just clusters of malignant cells. Bacteria can influence immune signaling, attract suppressive immune cells, and alter how tumors respond to therapy. Understanding these interactions opens the door to entirely new treatment strategies.

Broader Implications Beyond Head and Neck Cancer

While this research focused on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, its implications may extend far beyond one cancer type. Intratumoral bacteria have already been observed in breast, pancreatic, lung, and colorectal cancers.

If bacterial burden influences immunotherapy response across multiple cancers, future treatments may involve combining immunotherapy with microbiome-targeted interventions, such as antibiotics, probiotics, or precision microbial therapies.

A Shift in How Resistance Is Understood

These findings mark a significant shift in how scientists think about immunotherapy resistance. Instead of viewing resistance solely as a genetic or molecular issue within cancer cells, this research highlights unexpected biological contributors that exist alongside tumors.

By recognizing the tumor microbiome as a key player, researchers are expanding the toolkit for fighting cancer and improving outcomes for patients who currently have limited options.

Research Papers:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-025-01068-0

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-025-01067-1