Combination Therapy Against Brain Cancer Shows Remarkable Success in Preclinical Glioblastoma Models

Researchers at the UNC School of Medicine and the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy have reported a major advance that could potentially reshape how glioblastoma, one of the deadliest brain cancers, is treated. In a newly published study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the team demonstrated that combining the standard chemotherapy drug temozolomide (TMZ) with a laboratory chemical called EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) led to unprecedented survival and tumor eradication in several preclinical glioblastoma models.

Glioblastoma is notorious for being aggressive, fast-growing, and extremely difficult to treat. Despite decades of research, the standard of care has barely changed in over 20 years, and long-term survival remains rare. Against this backdrop, the results from this study stand out as both striking and hopeful.

Why Glioblastoma Remains One of the Toughest Cancers

Glioblastoma presents several unique challenges. The tumor grows rapidly within the brain, making it hard to control. Surgical removal is risky because tumors often infiltrate vital brain regions, limiting how much can safely be removed. On top of that, glioblastoma tumors are genetically diverse, meaning that a single treatment approach rarely works for all patients.

Currently, only about 7% of patients survive longer than five years after diagnosis. The frontline treatment involves surgery followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide, the only FDA-approved chemotherapy drug for glioblastoma. While TMZ can slow tumor growth, it often fails to eliminate the cancer entirely, and tumors frequently return, sometimes more aggressively than before.

EdU: From Lab Tool to Potential Cancer Therapy

EdU is not a traditional cancer drug. For years, it has been widely used in research labs as a tool to label newly synthesized DNA and track cell division. However, in earlier work, researchers in Aziz Sancar’s lab at UNC discovered something unexpected: EdU could selectively enter glioblastoma tumors in the brain and kill cancer cells while sparing healthy brain tissue.

This finding was significant for two reasons. First, EdU was shown to cross the blood–brain barrier, a major obstacle for many cancer drugs. Second, it appeared to exploit the fact that cancer cells divide much more rapidly than normal brain cells, making them more vulnerable to EdU incorporation into their DNA.

These discoveries set the stage for the new study, which asked a simple but powerful question: what happens if EdU is combined with TMZ?

Testing the Combination in Multiple Glioblastoma Models

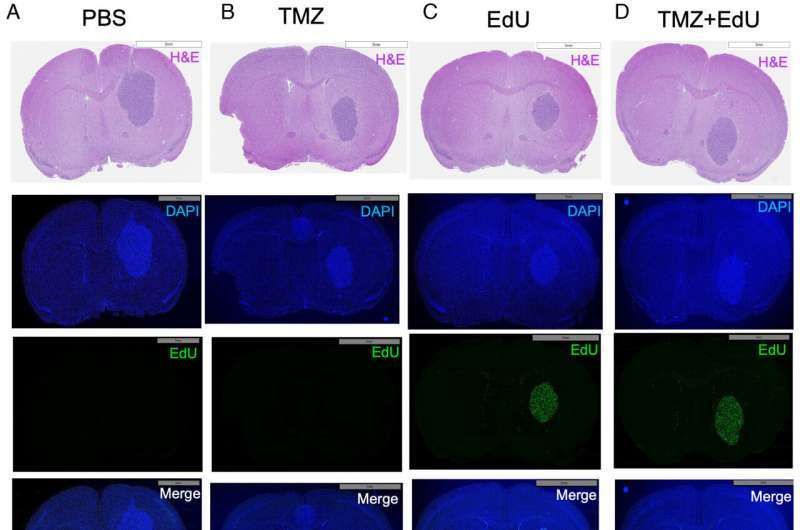

To answer this, the researchers conducted extensive testing across multiple glioblastoma cell lines, including U87, GBM8, and LN229. These cell lines originated from patients with glioblastoma and are commonly used in cancer research.

The team tested the drugs in both laboratory settings and in mouse models where tumors were implanted directly into the brain, closely mimicking how glioblastoma behaves in humans. To track tumor growth accurately, the cancer cells were engineered to emit light using a bioluminescent marker, allowing researchers to monitor tumor progression and regression in real time.

Dramatic Survival Results in Mouse Models

The most striking results came from experiments using mice implanted with U87 glioblastoma tumors:

- No treatment: mice died within about 30 days

- EdU alone: survival increased to just under 45 days

- TMZ alone: mice lived approximately 53 days

- TMZ + EdU combination: complete tumor elimination by day 23, with all mice surviving beyond 250 days, effectively the end of the study

In practical terms, the researchers described these mice as being functionally cured.

The results were similarly impressive in mice implanted with GBM8 tumors. Animals treated with combinations of 200 mg/kg EdU and either 1 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg TMZ remained alive and tumor-free after 170 days.

Safety and Toxicity Findings

Effectiveness alone is not enough for a therapy to move forward. The researchers also examined whether the combination therapy caused damage to healthy tissues, including the small intestine, liver, kidneys, spleen, lungs, and blood.

The findings were encouraging. The combination caused only mild and reversible changes, primarily affecting the small intestine, spleen, and blood. These effects were similar to what is already seen with standard chemotherapy and did not indicate severe or lasting toxicity.

Understanding the Synergistic Effect

A key takeaway from the study is that TMZ and EdU do more than simply add their effects together. In several models, the drugs worked synergistically, meaning their combined impact was greater than the sum of their individual effects.

This synergy likely stems from how the drugs interfere with DNA repair mechanisms. TMZ damages DNA in cancer cells, while EdU becomes incorporated into newly synthesized DNA, triggering repeated repair attempts. Together, these stresses appear to overwhelm glioblastoma cells, leading to their destruction.

Interestingly, not all tumors responded the same way, highlighting the complexity of glioblastoma biology.

Patient-Derived Tumors and Personalized Responses

To better reflect real-world tumors, the researchers also tested the therapy on fresh glioblastoma samples taken directly from patients during surgery. These samples were studied using the SLiCE (Screening Live Cancer Explants) model, which preserves both tumor cells and surrounding healthy brain tissue.

In these experiments, strong synergy was observed in one out of four patient tumors, while the other three showed additive effects. This variability underscores the importance of personalized treatment strategies, as not every glioblastoma responds identically to the same therapy.

The researchers believe that platforms like SLiCE could one day help doctors predict which patients are most likely to benefit from specific drug combinations before treatment begins.

Looking Toward Clinical Trials

While these results are still limited to preclinical models, the implications are substantial. The research team is now focused on additional studies, particularly in EGFR-mutated glioblastoma, the most common subtype seen in patients.

They are also working toward human clinical trials and eventual FDA approval, while continuing to explore how treatments can be customized based on individual tumor characteristics.

Why This Study Matters

This research is significant not just because it improves survival in animal models, but because it introduces a new therapeutic concept using a well-known laboratory compound in a novel way. If these results translate to humans, they could mark a meaningful step forward in treating a cancer that has seen little progress for decades.

Research paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2532187123