Vitamin C May Help Protect Fertility From a Harmful Environmental Chemical

New research from the University of Missouri suggests that something as familiar as vitamin C could play a protective role in reproductive health when the body is exposed to a harmful environmental chemical. The study focuses on potassium perchlorate, a chemical widely used in explosives, fireworks, and military applications, and its potential to interfere with male fertility. While the findings come from an animal model, they raise important questions about how everyday nutrients might help counteract environmental risks.

The research was led by Ramji Bhandari, an associate professor in the College of Arts and Science at the University of Missouri, whose work centers on understanding how environmental contaminants affect both wildlife and human health. Using a well-established fish model, the research team explored how potassium perchlorate impacts sperm production and whether vitamin C could reduce or prevent the damage.

What Is Potassium Perchlorate and Why Does It Matter?

Potassium perchlorate is increasingly being described as an emerging environmental contaminant. It is commonly found in explosives, fireworks, flares, and propellants, which means it can enter the environment through military activities, industrial processes, and even public celebrations. Once released, it can contaminate soil and water, leading to potential exposure in humans and wildlife.

Previous research has already linked perchlorate compounds to thyroid disruption, but less was known about their effects on reproductive health. This gap in knowledge was one of the reasons Bhandari became interested in studying the chemical more closely.

His curiosity was sparked over a decade ago after attending a Society of Toxicology conference, where data suggested that military personnel experience higher infertility rates than the general population. Some service members were found to have elevated levels of potassium perchlorate in their blood, likely due to repeated close proximity to explosives. This raised an important question: could this chemical be quietly interfering with fertility?

Why Use Fish to Study Fertility?

To investigate this, the research team turned to a small fish known as the Japanese rice fish, or medaka. While it might seem unusual to study human fertility through fish, medaka are actually a highly respected model organism in reproductive biology.

Medaka share many genetic pathways and reproductive processes with humans, particularly when it comes to sperm development. They also reproduce quickly and are easier to study in controlled laboratory environments, making them ideal for examining how chemicals affect reproductive systems over short periods.

What the Researchers Did

In the study, male medaka fish were divided into different exposure groups. Some fish were exposed only to potassium perchlorate, while others were exposed to both potassium perchlorate and vitamin C at the same time. A control group was maintained without exposure to the chemical.

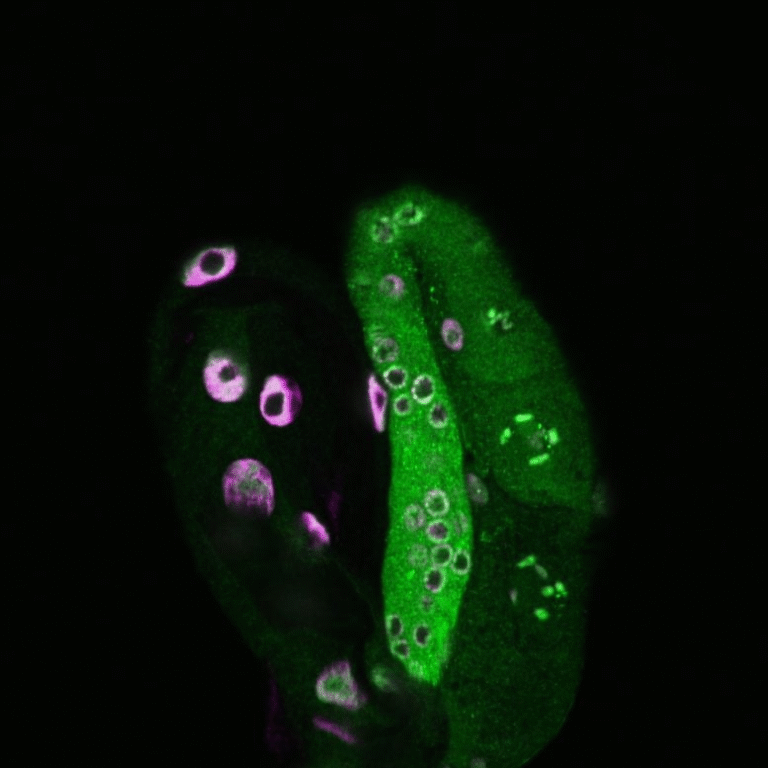

The goal was to observe changes in fertility rates, testicular structure, and the biological pathways involved in sperm production, also known as spermatogenesis.

The Impact of Potassium Perchlorate on Fertility

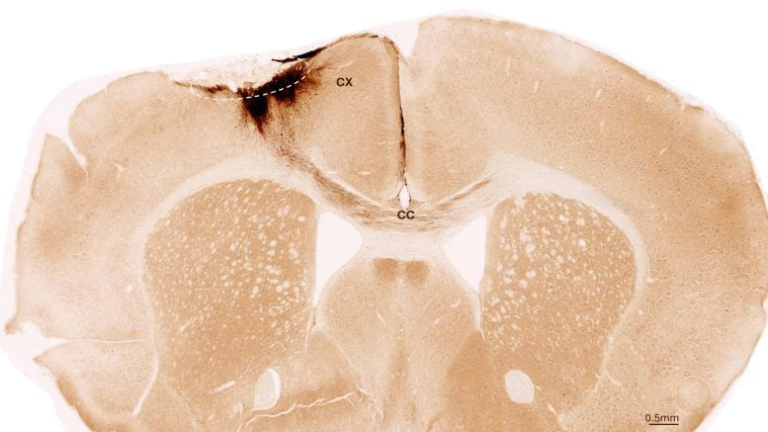

The results were striking. Male fish exposed solely to potassium perchlorate experienced a dramatic decline in fertility. Detailed examination revealed clear damage to the testes, along with disruptions in the normal process of sperm production.

At the molecular level, potassium perchlorate exposure caused oxidative stress, a condition where harmful molecules known as reactive oxygen species overwhelm the body’s natural defenses. This oxidative stress interfered with genes and signaling pathways essential for spermatogenesis, ultimately reducing the fish’s ability to produce healthy sperm.

In simple terms, the chemical created an internal environment that made it much harder for sperm to develop properly.

How Vitamin C Changed the Outcome

Things looked very different for fish that were exposed to both potassium perchlorate and vitamin C. In these fish, fertility rates were significantly improved compared to those exposed to the chemical alone. Their testes showed less structural damage, and many of the disrupted molecular pathways involved in sperm production were restored.

Vitamin C acted as a powerful antioxidant, neutralizing the oxidative stress caused by potassium perchlorate. By reducing this stress, vitamin C helped protect the delicate processes required for healthy sperm development.

The study demonstrated that vitamin C didn’t just reduce visible damage—it actively supported the biological mechanisms that drive male fertility.

Why Vitamin C Is Especially Interesting

Vitamin C is one of the most widely studied and commonly consumed nutrients in the world. It plays a role in immune function, collagen production, wound healing, and antioxidant defense. Its ability to counteract oxidative stress has already been well documented in many areas of health.

In the context of fertility, oxidative stress is a known risk factor for reduced sperm count, poor sperm motility, and DNA damage in sperm cells. This study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that antioxidants like vitamin C could help protect reproductive health under certain conditions.

What makes this research particularly compelling is that it connects a specific environmental exposure with a specific nutritional intervention, rather than making broad claims about supplements in general.

What This Means for Humans

It is important to be clear: this study was conducted in fish, not humans. While medaka are excellent models for reproductive research, results in animals do not automatically translate to humans.

That said, the findings are especially relevant for people who may be at higher risk of potassium perchlorate exposure, including those in military, industrial, or environmental settings. The study suggests that nutritional strategies could one day become part of broader efforts to reduce reproductive risks associated with environmental chemicals.

The researchers emphasize that more studies are needed, particularly in mammals and eventually in humans, before any preventative or therapeutic recommendations can be made.

The Bigger Picture of Environmental Fertility Risks

This research fits into a much larger scientific conversation about how environmental contaminants affect reproductive health. Chemicals that cause oxidative stress are increasingly being studied for their subtle, long-term effects on fertility, even at low levels of exposure.

Understanding these risks is critical not just for individuals, but for public health, environmental regulation, and occupational safety. Identifying ways to mitigate harm—whether through policy changes, reduced exposure, or nutritional support—could have wide-reaching benefits.

University of Missouri’s Role in Reproductive Research

The study also highlights the University of Missouri’s strong focus on reproductive biology and environmental health. Facilities like the NextGen Precision Health building and the university’s Advanced Technology Core Facilities provide researchers with the tools needed to study complex biological questions at both the molecular and organismal levels.

This kind of interdisciplinary environment allows scientists to connect environmental science, biology, and human health in meaningful ways.

Final Thoughts

This research does not suggest that vitamin C is a cure-all for fertility problems, nor does it imply that supplements alone can counteract environmental harm. What it does show is that nutrition and environmental health are deeply interconnected, and that even well-known vitamins may have underappreciated roles in protecting reproductive systems.

As environmental exposures continue to increase in modern life, studies like this one help clarify where risks exist—and where potential protective strategies might emerge.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c09514