Medications May Help the Aging Brain Cope With Surgery and Memory Impairment

Researchers are finding encouraging evidence that simple, well-known medications could help older brains better handle memory problems linked to both aging and surgery. Two new mouse studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign suggest that targeted pharmaceutical approaches may reduce cognitive decline, calm brain inflammation, and even restore memory-related brain functions—at least in preclinical models.

The work focuses on two major challenges commonly seen in older adults: postoperative cognitive impairment and age-related memory decline. While these conditions have different triggers, both are associated with changes in brain inflammation, neurotransmitter signaling, and hippocampal function. The researchers explored whether already-available drugs could counteract those changes.

Why cognitive decline after surgery matters

Cognitive problems following surgery are far more common than many people realize, particularly among older adults. Immediately after surgery, confusion and memory issues are expected. However, studies show that about 10% of adults over the age of 60 continue to experience deficits in learning, memory, and executive function even three months after surgery.

Given how frequently surgeries are performed in this age group, the total number of affected individuals is significant. Yet, teasing apart the causes of these deficits has been challenging. Is the damage coming from anesthesia, the physical trauma of surgery, or the inflammatory response that follows?

Many previous animal studies relied on young mice or exposed older mice to anesthesia without surgery, making it difficult to separate these effects. The Illinois research team designed experiments specifically to address this gap.

Study one: Propofol and postoperative cognitive impairment

The first study, published in PNAS Nexus, examined whether propofol, a commonly used anesthetic, could help prevent or reverse cognitive deficits after surgery in aged mice.

A more realistic surgical model

Instead of simply anesthetizing animals, the researchers performed actual surgery on aged mice—roughly equivalent to humans in late adulthood. The mice underwent an exploratory abdominal surgery under isoflurane anesthesia, mimicking the physiological stress experienced during real surgical procedures.

Propofol was administered intermittently, starting before surgery, at carefully controlled doses. This approach was important because propofol has a complex profile: while high or prolonged exposure can harm the brain, previous studies suggested that specific dosing regimens might enhance cognition under certain conditions.

Cognitive benefits that lasted beyond the drug

Mice receiving intermittent propofol performed significantly better on a wide range of cognitive tests, including tasks that measure working memory, recognition memory, spatial learning, and associative memory. Notably, these improvements persisted for up to five days after dosing, even though propofol itself is cleared from the body within hours.

This suggested that the drug was not just temporarily altering brain activity, but triggering long-lasting biological changes.

What changed inside the brain

Detailed molecular analysis revealed several important effects:

- An increase in GABA receptor subtypes, particularly alpha-5 GABA-A receptors, on the surface of hippocampal neurons

- A reduction in markers associated with neuroinflammation

- Lower levels of proteins linked to cell death

- Reduced activation of microglia, the immune cells of the brain

The hippocampus is a central hub for memory formation, and GABA signaling plays a key role in regulating learning and neural stability. By increasing the availability of specific GABA receptors on neuron surfaces, propofol appeared to restore a healthier balance in aging brain circuits.

Importantly, mice that did not receive propofol showed none of these protective changes.

Study two: Intranasal insulin and age-related memory decline

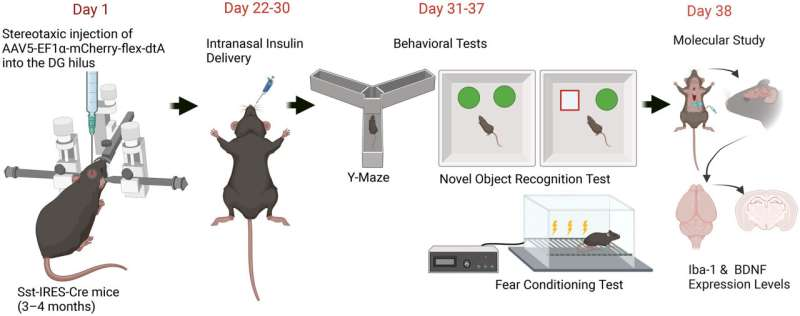

The second study, published in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives, focused on age-related memory impairment rather than surgery. The researchers tested whether intranasal insulin, a noninvasive treatment previously explored in Alzheimer’s disease models, could improve memory in a broader aging context.

A “pseudo-aged” mouse model

To study hippocampal aging more precisely, the team developed a unique pseudo-aging mouse model. Instead of waiting for mice to grow old naturally, they selectively eliminated a specific group of neurons—somatostatin-positive GABAergic interneurons—in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.

Loss of these neurons is a well-documented feature of hippocampal aging in both humans and animals. Removing them in young adult mice produces memory deficits that closely resemble those seen in older brains.

Insulin delivered through the nose

The researchers administered intranasal insulin daily for nine days. This method allows insulin to reach the brain directly, bypassing the bloodstream and minimizing systemic side effects.

The treatment was given to both pseudo-aged mice and normal control mice.

Memory improvements tied to inflammation reduction

The results were striking but selective:

- Pseudo-aged mice showed clear improvements in working memory, recognition memory, and associative memory

- Control mice showed no significant cognitive changes

On a molecular level, pseudo-aged mice had elevated levels of proteins involved in neuroinflammatory signaling, including markers linked to microglial activation. Intranasal insulin reversed these increases, effectively calming inflammatory pathways in the hippocampus.

The treatment also restored levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein essential for synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory.

A shared theme: neuroinflammation and GABA signaling

Although the two studies focused on different problems—postoperative impairment and age-related memory decline—they converged on similar mechanisms.

Both interventions:

- Reduced neuroinflammation

- Altered GABAergic signaling

- Improved performance across multiple cognitive domains

- Targeted the hippocampus, a region highly vulnerable to aging

The researchers are now exploring whether alpha-5 GABA-A receptors, which increased after propofol treatment, also play a role in the cognitive benefits seen with intranasal insulin. Identifying the exact neuron types responsible for these effects is another key next step.

Why these findings matter (and what they don’t mean yet)

These studies do not suggest that older adults should receive propofol as a cognitive enhancer or start using intranasal insulin for memory problems. The work is preclinical, conducted entirely in mice under controlled conditions.

However, the findings offer a clear blueprint for future research:

- They identify specific molecular targets

- They use clinically relevant drugs

- They demonstrate lasting cognitive effects

- They highlight the importance of dose, timing, and delivery method

Because both drugs are already well-characterized in humans, they may be more feasible candidates for carefully designed clinical trials than entirely new compounds.

Broader context: aging, surgery, and the brain

As life expectancy increases, more people are undergoing surgery later in life. At the same time, age-related memory decline remains a major public health concern. Understanding how inflammation, inhibitory signaling, and hippocampal circuits interact in the aging brain is critical for developing interventions that preserve cognitive health.

These studies add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the aging brain retains a surprising capacity for recovery, provided the right biological pathways are targeted.

Research papers referenced

Noncanonical sustained actions of propofol reverse surgery-induced microglial activation and cognitive impairment in aged mice (PNAS Nexus, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf213

Intranasal Insulin Mitigates Memory Impairment and Neuroinflammation in a Mouse Model of Hippocampal Aging (Pharmacology Research & Perspectives, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.70186