Digital Memory Palace Shows How Familiar Places Strengthen the Way We Form Memories

Our connection between place and memory is something most of us recognize instantly. Walking into a childhood bedroom, an old classroom, or even a long-forgotten café can suddenly unlock vivid memories we didn’t know were still there. A new neuroscience study now explains why this happens, showing that familiar locations play a powerful role in how memories are encoded, stored, and later retrieved.

Researchers from Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, and Princeton University have published new findings in Nature Human Behaviour that shed light on the brain mechanisms linking spatial environments and memory formation. Using a carefully designed virtual reality “memory palace,” the team demonstrated that when people have a strong mental map of a place, they are significantly better at remembering new information associated with that place.

A Collaboration Across Leading Universities

The research was led by Chris Baldassano, professor of psychology at Columbia University, Rolando Masís-Obando, a postdoctoral researcher at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the study, and Kenneth A. Norman, professor of psychology at Princeton University. Together, they set out to understand how existing knowledge about spaces influences our ability to form new memories.

Rather than focusing on memory in isolation, the team explored how memories are built on top of prior spatial knowledge. Their work also helps explain why some experiences stick with us for years, while others fade surprisingly fast.

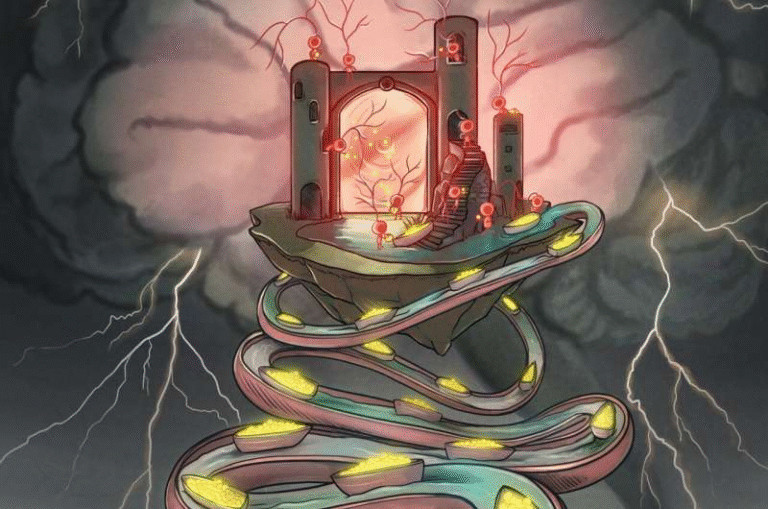

Building a Virtual Memory Palace

To investigate this, the researchers created a digital memory palace using virtual reality technology. The palace consisted of 23 unique rooms, each designed to be as distinct as possible from the others. The rooms varied in shape, size, layout, decorations, and even background sounds. Some spaces were large and surreal, like a massive dome filled with floating rocks, while others were small and intimate, such as a room centered around a glowing campfire.

The goal was to ensure that each room produced a clearly distinguishable pattern of brain activity. If two rooms felt too similar, the neural signals associated with them might overlap, making it harder to study how the brain represents individual locations.

Learning the Space Before Testing Memory

Participants didn’t jump straight into memorization. First, they spent time learning the layout of the virtual palace through exploration and interactive games. This allowed them to develop mental maps of the environment, similar to how someone gradually becomes familiar with their own home.

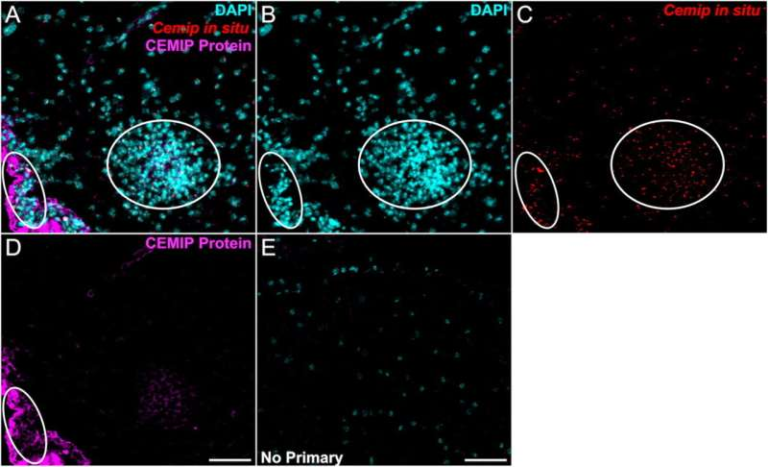

After a 24-hour break, participants returned for brain imaging. While undergoing functional MRI (fMRI) scans, they watched videos of each room. This allowed researchers to measure how consistently and clearly each room was represented in the brain.

Only after this step did the real memory test begin.

Objects, Locations, and Memory Encoding

Participants re-entered the virtual palace, but this time, new objects had been placed inside each room. They were given 15 minutes to memorize which objects appeared in which rooms. Later, they returned to the MRI scanner and were asked to recall both the objects and their locations.

By analyzing brain activity during recall, the researchers could see how strongly each object was mentally “reinstated” along with its associated room. This approach allowed them to directly link the quality of spatial representations to memory performance.

Strong Mental Maps Lead to Stronger Memories

The findings were clear. Objects placed in rooms with more stable and distinct neural patterns were remembered better. In simple terms, when participants had built a high-quality mental map of a room, that room became a better foundation for encoding new memories.

Even more striking, the researchers could predict which objects would be well remembered before the objects were ever introduced. By looking at how clearly a participant’s brain represented a room, they could tell whether anything placed there would later be recalled successfully.

This suggests that memory formation depends not just on attention or effort in the moment, but also on the strength of prior knowledge. If the mental “foundation” is weak, new memories struggle to stick.

Not All Rooms Are Equal

The study also found that some rooms were consistently more memorable across participants. Smaller rooms with windows and multiple corners tended to produce more reliable neural patterns. These features may provide more visual anchors, helping the brain build a richer spatial representation.

This insight could help researchers understand why certain real-world environments, like cozy rooms or well-structured spaces, feel easier to remember than large, open, or visually repetitive areas.

Explaining the Method of Loci

These findings offer strong scientific support for the Method of Loci, a memorization technique used since ancient times. This method involves imagining information placed along a sequence of familiar locations, such as rooms in a house or landmarks along a walk.

The study shows that this technique works because familiar spatial contexts provide a stable neural scaffold. Even when the locations are only imagined, the brain treats them as reliable anchors for new information, improving recall without requiring physical presence in the space.

Why This Matters for Learning and Memory

Beyond explaining everyday memory experiences, this research has broader implications. It suggests that learning may be more effective when new information is connected to well-established knowledge structures. In educational settings, this could mean building strong conceptual frameworks before introducing complex details.

The findings also hint at future applications for neuroimaging-based learning strategies, where gaps in prior knowledge might be identified and strengthened before new material is introduced. In clinical contexts, understanding how spatial representations support memory could inform treatments for memory-related disorders.

The Brain’s Spatial-Memory Connection

Decades of research have shown that brain regions involved in navigation, particularly the hippocampus, are also central to memory. This study adds to that understanding by showing how the reliability of spatial neural patterns directly influences memory encoding.

Virtual reality proved to be a powerful tool in this work, allowing researchers to control environments with precision while still engaging the brain’s natural spatial systems. As VR technology continues to improve, it is likely to play an even larger role in cognitive neuroscience research.

Looking Ahead

This study provides a detailed explanation of why where something happens matters just as much as what happens. Familiar places don’t just trigger memories; they actively help shape them at the neural level. By revealing how spatial knowledge supports memory formation, the research opens new pathways for studying learning, memory loss, and even the design of spaces that help us remember better.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02379-z