Gut Bacteria Protect Mice With Influenza A From Deadly Bacterial Pneumonia, New Study Finds

Influenza is often thought of as a dangerous illness on its own, but history and modern medicine agree on one thing: much of the real damage caused by flu outbreaks comes after the virus has already done its part. Secondary bacterial pneumonia has long been one of the biggest killers following influenza infections, and a new study now highlights an unexpected ally in the fight against this deadly complication — gut bacteria.

Researchers from the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University have found that specific intestinal bacteria can dramatically protect mice infected with influenza A virus from developing severe, often fatal, bacterial pneumonia. The findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal Science Immunology and add powerful evidence to the growing idea that the gut and lungs are more closely connected than previously believed.

Understanding the Problem of Post-Influenza Pneumonia

Influenza weakens the body in multiple ways, but one of its most dangerous effects is how it disrupts the immune system in the lungs. After a flu infection, the respiratory tract becomes highly vulnerable to invasion by bacteria that normally might not cause severe disease. These secondary bacterial infections are responsible for a large share of hospitalizations and deaths during seasonal flu outbreaks and pandemics alike.

The Georgia State study focused on understanding why some individuals are more vulnerable to these secondary infections than others. Instead of looking only at lung immunity, the researchers turned their attention to the intestinal microbiome, the massive ecosystem of bacteria living in the gut.

The Role of Segmented Filamentous Bacteria

The research team investigated a specific type of gut bacteria known as segmented filamentous bacteria, or SFB. These bacteria naturally occur in the intestines of many mammals, but not all individuals carry them. SFB are unusual in that they attach closely to the intestinal lining rather than floating freely in the gut.

Using mouse models, the researchers examined whether the presence or absence of SFB influenced how animals responded to bacterial infections following influenza A virus exposure. After infecting mice with influenza A, they introduced common respiratory bacterial pathogens that are known to cause post-flu pneumonia.

These pathogens included Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus — three bacteria that are frequently implicated in severe pneumonia cases in humans as well.

The results were striking. Mice that carried SFB in their intestines showed dramatically higher survival rates and significantly reduced disease severity compared to mice that lacked these bacteria. In contrast, mice without SFB were highly susceptible to lethal bacterial pneumonia after influenza infection.

How Gut Bacteria Protect the Lungs

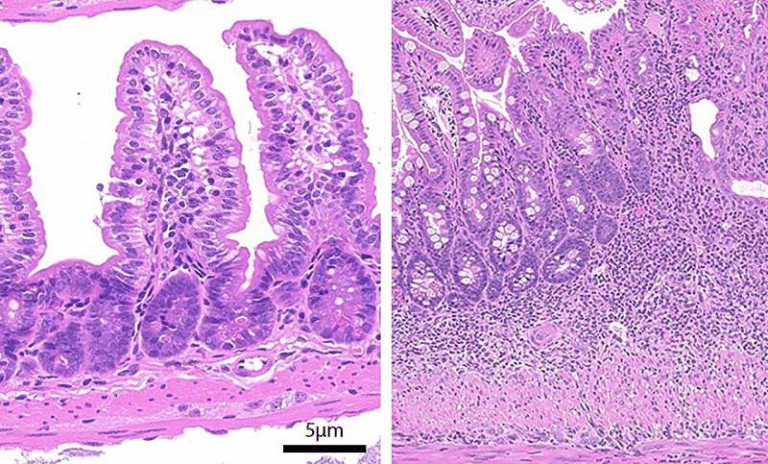

One of the most fascinating aspects of the study is how bacteria in the gut were able to influence immune defenses in the lungs. SFB do not leave the intestine or migrate to the respiratory tract. Instead, their protective effect was traced to alveolar macrophages, specialized immune cells that reside in the lungs.

Alveolar macrophages act as the lungs’ first line of defense, engulfing and destroying bacteria before they can cause serious infection. However, influenza A virus is known to impair these cells, leaving the lungs exposed and poorly defended.

The researchers discovered that SFB somehow reprogrammed alveolar macrophages to resist this influenza-induced dysfunction. Even after viral infection, these immune cells retained their ability to fight off bacterial invaders effectively.

Importantly, this reprogramming occurred through epigenetic changes, meaning that SFB altered how genes were expressed in the lung macrophages without changing the underlying DNA. This allowed the macrophages to maintain a robust antibacterial response despite the damage typically caused by the flu virus.

Why This Discovery Matters

Secondary bacterial pneumonia has played a central role in nearly every major influenza pandemic, including the devastating 1918 Spanish flu, where bacterial infections were responsible for many of the deaths. Even today, modern antibiotics and vaccines have not eliminated the threat, especially among older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

This study suggests that gut microbiota composition could be a crucial factor in determining who survives severe influenza infections and who does not. The presence of a single bacterial species in the intestine was enough to dramatically alter outcomes in the lungs — a finding that underscores the power of the gut-lung immune axis.

The researchers emphasized that while the study was conducted in mice, the biological mechanisms involved are highly relevant to humans. Variations in gut microbiomes between individuals may help explain differences in flu severity that cannot be accounted for by age, vaccination status, or underlying health conditions alone.

Implications for Future Treatments

Rather than suggesting that people should try to acquire SFB directly, the researchers are focused on understanding the mechanism behind the protection. By identifying the molecular signals and pathways involved, scientists hope to develop new pharmacological therapies that mimic the immune-boosting effects of SFB.

Such treatments could potentially be used to strengthen lung immunity following viral infections, reducing the risk of bacterial pneumonia not only after influenza but also after other respiratory viruses.

This approach could be especially valuable during pandemics, when viral infections spread rapidly and healthcare systems are overwhelmed by secondary complications.

The Gut–Lung Axis Explained

The idea that gut bacteria can influence lung health may sound surprising, but it fits into a broader scientific concept known as the gut–lung axis. Over the past decade, researchers have uncovered numerous links between intestinal microbes and immune responses in distant organs, including the lungs.

Gut bacteria can release metabolites, immune-modulating molecules, and signaling compounds that circulate throughout the body. These signals help train immune cells, shaping how they respond to infections long before pathogens ever appear.

In this study, SFB acted as a powerful immune trainer, ensuring that lung macrophages were better prepared to handle bacterial threats after influenza infection.

What This Means for Human Health

While this research does not immediately translate into a probiotic pill for flu patients, it opens the door to new strategies for preventing one of influenza’s deadliest consequences. It also reinforces the idea that maintaining a healthy and diverse gut microbiome may play a broader role in immune resilience than previously appreciated.

Future studies will need to determine whether similar bacteria or mechanisms exist in humans and how they can be safely harnessed for therapeutic use. Still, the findings provide a compelling example of how interconnected the body’s systems truly are.

Final Thoughts

This study highlights a remarkable insight: adding one specific bacterium to the gut can completely change how the lungs respond to infection. By protecting alveolar macrophages from influenza-induced damage, SFB helped mice survive bacterial pneumonia that would otherwise have been fatal.

As scientists continue to unravel the complex relationships between microbes and immunity, discoveries like this bring us closer to smarter, more targeted ways of preventing severe respiratory disease — not just by fighting pathogens directly, but by strengthening the body’s own defenses from within.

Research paper reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciimmunol.adt8858