Mega-Analysis Links Widespread Brain Shrinkage to Memory Decline in Aging

A large international research effort has provided one of the clearest pictures yet of how age-related brain shrinkage is connected to memory decline. By pooling brain scans and memory test results from thousands of cognitively healthy adults, researchers have shown that memory changes in aging are tied to widespread structural changes across the brain, not just deterioration in one or two well-known regions.

The study, published in Nature Communications, analyzed data at an unprecedented scale, allowing scientists to move beyond smaller, isolated studies and examine long-term patterns of brain aging with far greater precision.

A Massive Dataset Spanning the Adult Lifespan

This research stands out mainly because of its size and scope. Scientists combined data from 13 independent longitudinal studies, bringing together:

- More than 10,000 MRI brain scans

- Over 13,000 memory assessments

- 3,700 cognitively healthy adults

- Participants spanning a wide range of adult ages

Because many individuals were scanned and tested multiple times over several years, researchers could directly link changes in brain structure with changes in memory performance within the same people over time. This approach is far more powerful than cross-sectional studies that compare different people of different ages at a single moment.

The focus was strictly on cognitively healthy aging, meaning participants did not have dementia or diagnosed neurodegenerative disease at the time of testing. This allowed the researchers to isolate memory decline associated with normal aging processes, rather than clinical disease alone.

Memory Decline Is Not About Just One Brain Region

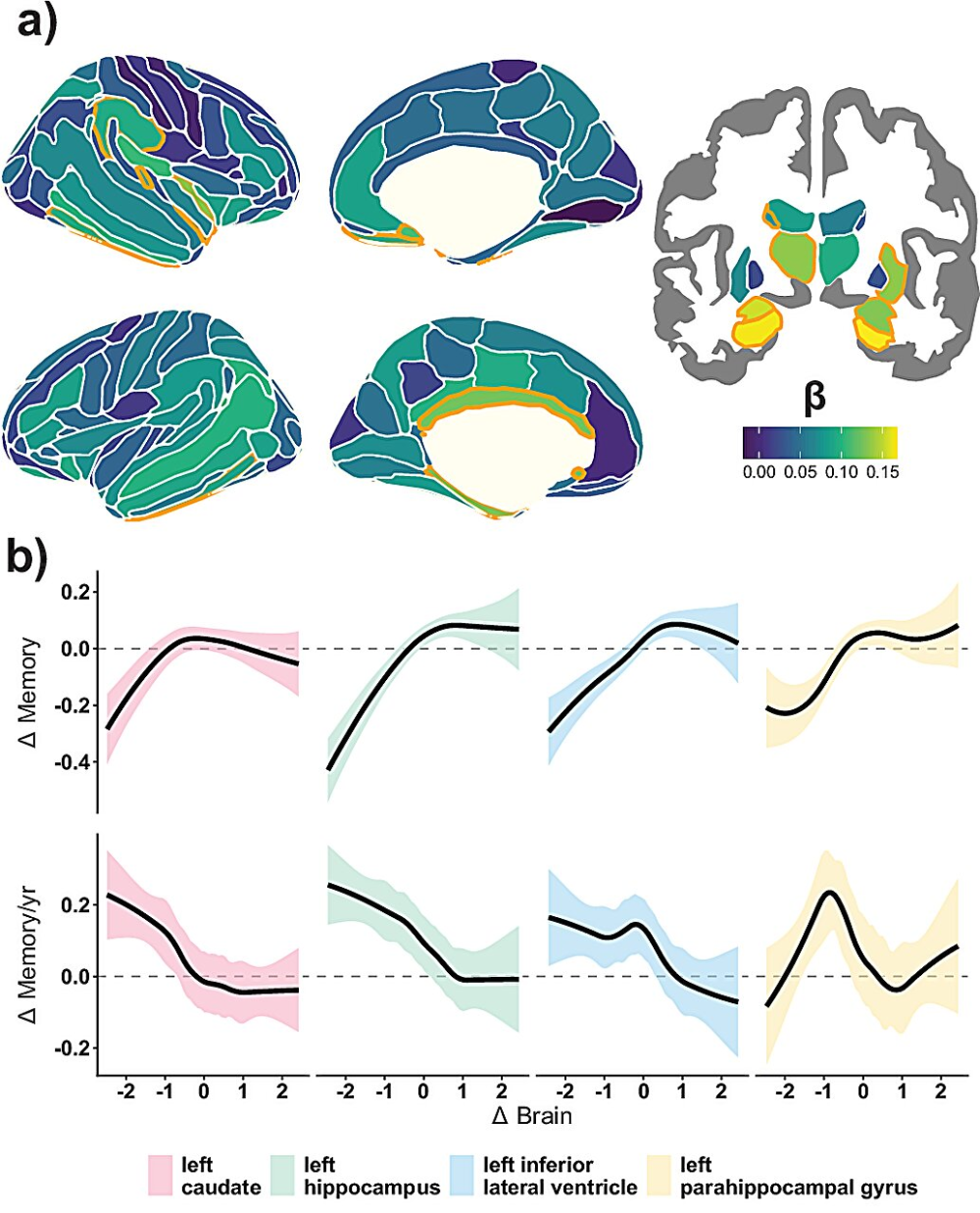

One of the most important findings is that memory decline in aging reflects a distributed pattern of brain vulnerability.

The hippocampus, a brain region long associated with memory formation and retrieval, did show the strongest link between volume loss and declining memory. This reinforces decades of research highlighting its sensitivity to aging.

However, the analysis revealed that memory decline is not confined to the hippocampus. Many other cortical and subcortical regions across the brain also showed meaningful associations between structural shrinkage and memory performance. These effects were smaller than those seen in the hippocampus, but they were consistent and widespread.

Rather than pointing to one failing “memory center,” the results suggest that aging affects large-scale brain networks, with memory suffering as these interconnected systems gradually lose structural integrity.

A Gradient of Brain Vulnerability

When researchers examined the strength of brain–memory relationships across regions, a clear gradient pattern emerged. The hippocampus sat at the top of this gradient, followed by progressively smaller but still significant effects across other brain areas.

This pattern supports the idea of macrostructural brain vulnerability, where memory decline reflects the cumulative impact of shrinkage across many regions rather than isolated damage. In practical terms, this means that memory performance depends on the overall health of brain structure, not just the condition of a single region.

The Relationship Is Strongly Nonlinear

Another key discovery was that the link between brain shrinkage and memory decline is not linear.

People with above-average rates of structural brain loss experienced disproportionately larger drops in memory performance. Instead of memory declining at a steady pace, the data suggest that once brain shrinkage crosses certain levels, cognitive consequences accelerate rapidly.

This nonlinear pattern appeared consistently across multiple brain regions, reinforcing the idea that memory decline can reach a tipping point, where structural damage leads to faster and more noticeable cognitive change.

This finding may help explain why some older adults experience relatively stable memory for years, followed by a more sudden decline later in life.

Aging Amplifies the Brain–Memory Connection

Age itself played a major role in shaping these relationships. The association between structural brain change and memory decline was much stronger in older adults than in younger participants.

In earlier adulthood, variations in brain volume were less tightly linked to memory performance. As people aged, however, structural losses became increasingly predictive of memory decline. This suggests that the brain becomes less resilient to structural change as aging progresses.

In other words, the same amount of brain shrinkage may have minimal cognitive impact earlier in life, but far greater consequences later on.

Genetics Matter, But They Are Not the Whole Story

The researchers also examined the role of APOE ε4, a genetic variant strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk.

While individuals carrying APOE ε4 tended to show faster rates of brain shrinkage and memory decline, the overall relationship between structural change and memory performance looked remarkably similar regardless of genetic status.

This indicates that APOE ε4 may influence how quickly changes occur, but it does not fundamentally alter the brain-wide vulnerability pattern linking structure to memory. Memory decline in aging, according to the findings, reflects broad biological processes, not just the presence of a single high-risk gene.

Why This Study Changes How We Think About Brain Aging

Traditionally, aging research has often focused on specific regions or disease-related markers. This mega-analysis pushes the field toward a more holistic understanding of cognitive aging.

Key implications include:

- Memory decline is a network-level phenomenon, not a localized defect

- Structural brain aging follows nonlinear trajectories, with accelerating effects at higher levels of shrinkage

- Individual differences in brain aging help explain why memory decline varies so widely among older adults

These insights may help researchers identify people at higher risk for accelerated cognitive decline earlier, before symptoms become severe.

What This Means for Future Research and Interventions

Understanding memory decline as a reflection of global brain structure has practical implications. Preventive strategies may need to focus on maintaining overall brain health rather than targeting one specific region or biomarker.

This could include lifestyle factors known to support brain structure, such as physical activity, cardiovascular health, cognitive engagement, and sleep quality. It also suggests that future therapies might aim to strengthen network resilience across the brain, rather than narrowly addressing single areas.

Extra Context: Why Structural MRI Matters

Structural MRI allows scientists to measure brain volume and thickness with high precision. Longitudinal MRI, where the same person is scanned multiple times, is especially powerful because it captures true change over time, not just differences between individuals.

By combining thousands of scans, this study minimized noise and variability, revealing patterns that smaller studies might miss. This approach is becoming increasingly important as researchers try to understand complex processes like aging, where changes unfold slowly and unevenly over decades.

A More Nuanced Picture of Aging and Memory

Overall, this mega-analysis paints a more nuanced and realistic picture of how memory changes with age. Rather than viewing memory decline as an inevitable result of one shrinking brain structure or one risky gene, the findings suggest it emerges from gradual, widespread changes that accumulate across the brain.

By mapping these patterns in detail, researchers are now better equipped to understand why aging affects individuals so differently—and how we might better support cognitive health throughout the lifespan.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/10.1038/s41467-025-66354-y