Getting a Grip on Aging as Scientists Identify a Brain Region Closely Linked to Frailty

A growing body of research suggests that aging is not just about muscles weakening over time, but about how the brain and body work together. A new study from researchers at the University of California, Riverside adds an important piece to that puzzle by identifying a specific deep-brain region that strongly predicts physical strength in older adults. The findings point to the brain’s caudate nucleus as a key player in grip strength, a widely used marker of frailty and overall health in aging populations.

Grip strength may seem like a simple measure, but clinicians increasingly view it as a powerful indicator of physical resilience. Lower grip strength has been linked to a higher risk of disability, slower recovery from illness, and even increased mortality. What this study shows is that grip strength is not only about muscles and bones—it is also deeply connected to how the brain functions during physical effort.

Why Grip Strength Matters in Aging Research

Grip strength is commonly measured using a handheld device called a dynamometer. Participants squeeze the device as hard as they can, and the maximum force is recorded. This straightforward test has become one of the most reliable ways to assess frailty, because it reflects coordination between muscles, nerves, and the brain.

As people age, grip strength tends to decline, often before more obvious signs of physical weakness appear. Because of this, researchers are keen to understand what drives these changes and whether early warning signs can be detected before frailty takes hold.

How the Study Was Conducted

The UC Riverside research team studied 60 older adults living in the Riverside area, evenly split between men and women. All participants took part in three separate functional MRI sessions, during which their brain activity was recorded while they performed a maximum grip strength task inside the scanner.

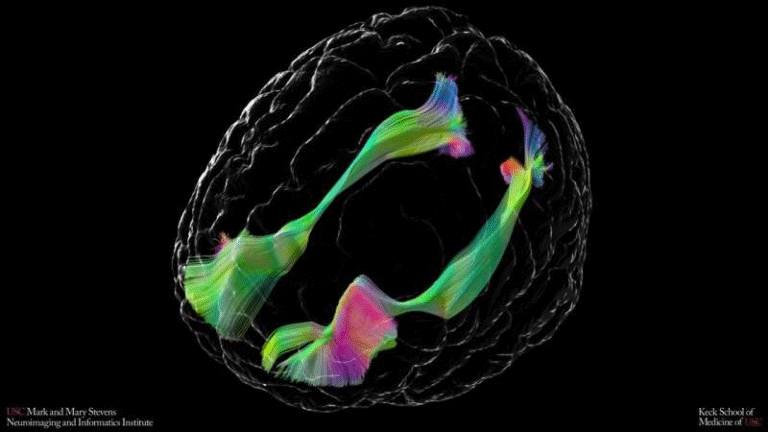

Functional MRI allowed the researchers to observe real-time changes in blood flow across the brain while participants were actively squeezing the device. This approach is different from many earlier studies that relied on brain structure or resting-state scans, where participants are not performing any task.

To ensure the results reflected brain activity rather than physical differences, the researchers normalized the data to account for sex, muscle mass, and body size. This allowed them to isolate neural factors linked specifically to grip strength performance.

Mapping the Brain’s Communication Network

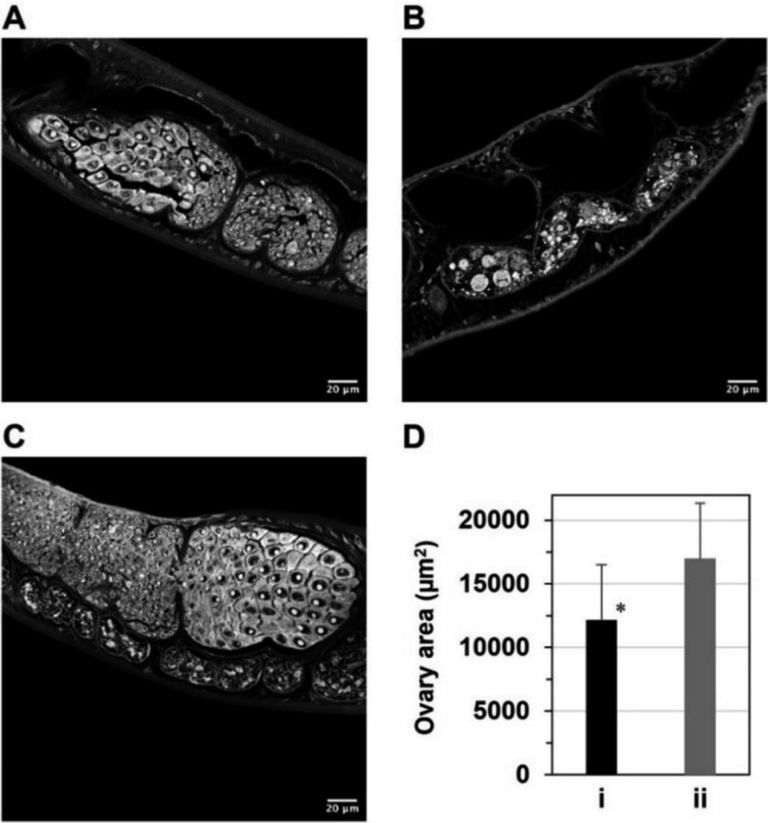

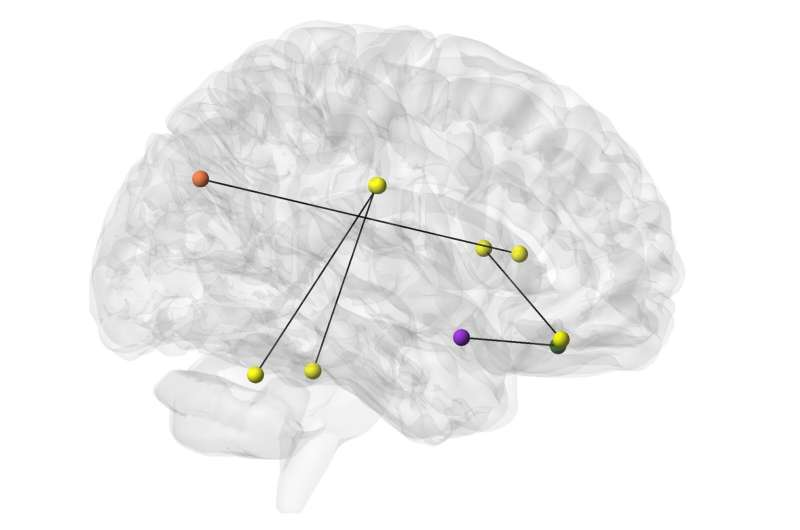

Rather than focusing on a single brain area from the start, the team analyzed each participant’s functional connectome. A functional connectome is a comprehensive map of how different brain regions communicate with each other during a task.

Using advanced connectome-based predictive modeling, the researchers compared patterns of brain connectivity with grip strength measurements. The goal was to identify which neural networks best predicted how much force a person could produce.

Out of dozens of regions examined, one stood out clearly.

The Caudate Nucleus Takes Center Stage

The strongest predictor of grip strength was the caudate nucleus, a structure located deep within the brain. The caudate is part of the basal ganglia and is traditionally known for its role in movement control, learning, and decision-making. However, its direct connection to muscular strength and frailty had not been clearly established before this study.

Participants who showed stronger blood flow and greater functional connectivity in the caudate nucleus consistently demonstrated higher grip strength. This relationship remained statistically significant even after controlling for sex and muscle mass.

The prominence of the caudate suggests it may function as a central hub that integrates cognitive, motor, and motivational signals during physical exertion, especially in older adults.

Other Brain Regions Also Showed Links

While the caudate nucleus emerged as the most important predictor, it was not the only region associated with grip strength. The study also found weaker but notable connections involving:

- The tail of the hippocampus, a region involved in memory and spatial processing

- The anterior cingulate cortex, which plays a role in attention, emotion, and effort regulation

These findings reinforce the idea that physical strength in aging is supported by a distributed brain network, not just motor regions alone.

What This Means for Understanding Frailty

Frailty is often defined as a reduced ability to recover from stressors such as illness or injury. It is not caused by muscle loss alone, but by a complex interaction between physical, cognitive, and emotional systems.

By linking grip strength to specific brain networks, this study suggests that frailty may begin in the brain before it becomes visible in the body. Changes in neural connectivity could potentially serve as early warning signs, allowing clinicians to identify individuals at risk sooner than current methods allow.

This also opens the door to new types of interventions. Just as physical exercise strengthens muscles, future therapies may aim to strengthen neural connections through targeted cognitive training, motor practice, or brain-based interventions.

Why Task-Based Brain Imaging Is Important

One of the most significant aspects of this research is its use of task-based functional MRI. Instead of measuring brain activity at rest, the researchers captured neural function while participants were actively exerting physical effort.

This real-time approach provides a more accurate picture of how the aging brain supports movement and strength. It also helps explain why grip strength is such a powerful marker of overall health—it reflects the coordinated performance of multiple brain systems working together.

Broader Context: The Brain–Body Connection in Aging

Over the past decade, aging research has increasingly emphasized the brain–body connection. Studies have shown that declines in cognitive function, motivation, and emotional regulation can directly influence physical performance.

The caudate nucleus is particularly interesting in this context because it sits at the intersection of motor control and cognitive decision-making. Its involvement in grip strength suggests that physical effort is not just a mechanical process, but one that relies on motivation, planning, and neural efficiency.

Understanding this connection may help explain why some older adults maintain strength and independence longer than others, even when muscle mass appears similar.

Limitations and Next Steps

While the results are promising, the researchers note that the study was conducted with a relatively small and geographically limited sample. Larger and more diverse populations will be needed to confirm the findings and determine how broadly they apply.

Future research may also explore whether changes in caudate connectivity can predict strength decline over time, or whether targeted interventions can preserve or enhance these neural networks.

A Step Toward Earlier Detection and Prevention

This study represents an important step toward viewing aging as a gradual, measurable process rather than a sudden decline. By identifying neural markers linked to physical strength, scientists are moving closer to tools that could help older adults maintain independence and quality of life for longer.

Grip strength, once seen as a simple muscle test, now appears to be a window into the health of the aging brain itself.

Research paper:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2025.1697908/full