Age-Specific Treatments for the Same Infection May Become Essential as Antibiotic Resistance Worsens

Dealing with an infection has never been as simple as just eliminating the invading pathogen. While killing bacteria, viruses, or fungi is important, the body also has to carefully manage its own immune response. If that response becomes too aggressive, it can cause serious damage to tissues and organs. This balancing act is known as disease tolerance, and new research suggests it may work very differently depending on a patient’s age.

A major study led by researchers at the Salk Institute and published in Nature on January 14, 2026, reveals that younger and older individuals may need completely different treatments for the same infection, particularly in life-threatening conditions like sepsis. The findings come at a critical time, as the global antibiotic resistance crisis continues to undermine traditional approaches to treating infections.

Understanding Disease Tolerance and Why It Matters

When an infection strikes, the immune system launches an attack to eliminate the pathogen. At the same time, the body activates disease tolerance mechanisms that limit the damage caused by inflammation, immune cell activity, and metabolic stress. These mechanisms don’t reduce the number of pathogens directly. Instead, they help the body survive the infection without destroying itself.

For years, most treatments have focused on pathogen clearance, mainly through antibiotics. However, researchers have increasingly realized that many patients die even after the infection is controlled. In these cases, it is often the body’s own immune response that causes fatal organ damage.

This realization has pushed scientists to explore disease tolerance as a potential therapeutic target. But one critical question remained largely unanswered: do disease tolerance mechanisms change with age?

Sepsis as a Model for Studying Immune Overreaction

To explore this question, the researchers focused on sepsis, one of the most dangerous and complex immune-related conditions. Sepsis occurs when the immune system’s response to an infection spirals out of control, leading to widespread inflammation, organ failure, and often death.

Sepsis can be triggered by bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections. It affects people of all ages and is responsible for about 20 percent of all global deaths. Standard treatment relies heavily on antibiotics, sometimes combined with anti-inflammatory drugs. However, these approaches have major limitations. Antibiotics do not address immune-driven tissue damage, and broad anti-inflammatory drugs can suppress protective immune functions if used too aggressively or too late.

With antibiotic resistance rising worldwide, sepsis has become an especially urgent problem. Resistant infections are harder to treat, and even when pathogens are controlled, patients may still succumb to immune-related damage.

How the Study Was Designed

The research team, led by Janelle Ayres, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and professor at the Salk Institute, used a carefully controlled mouse model of sepsis. They divided mice into two groups: young mice and aged mice.

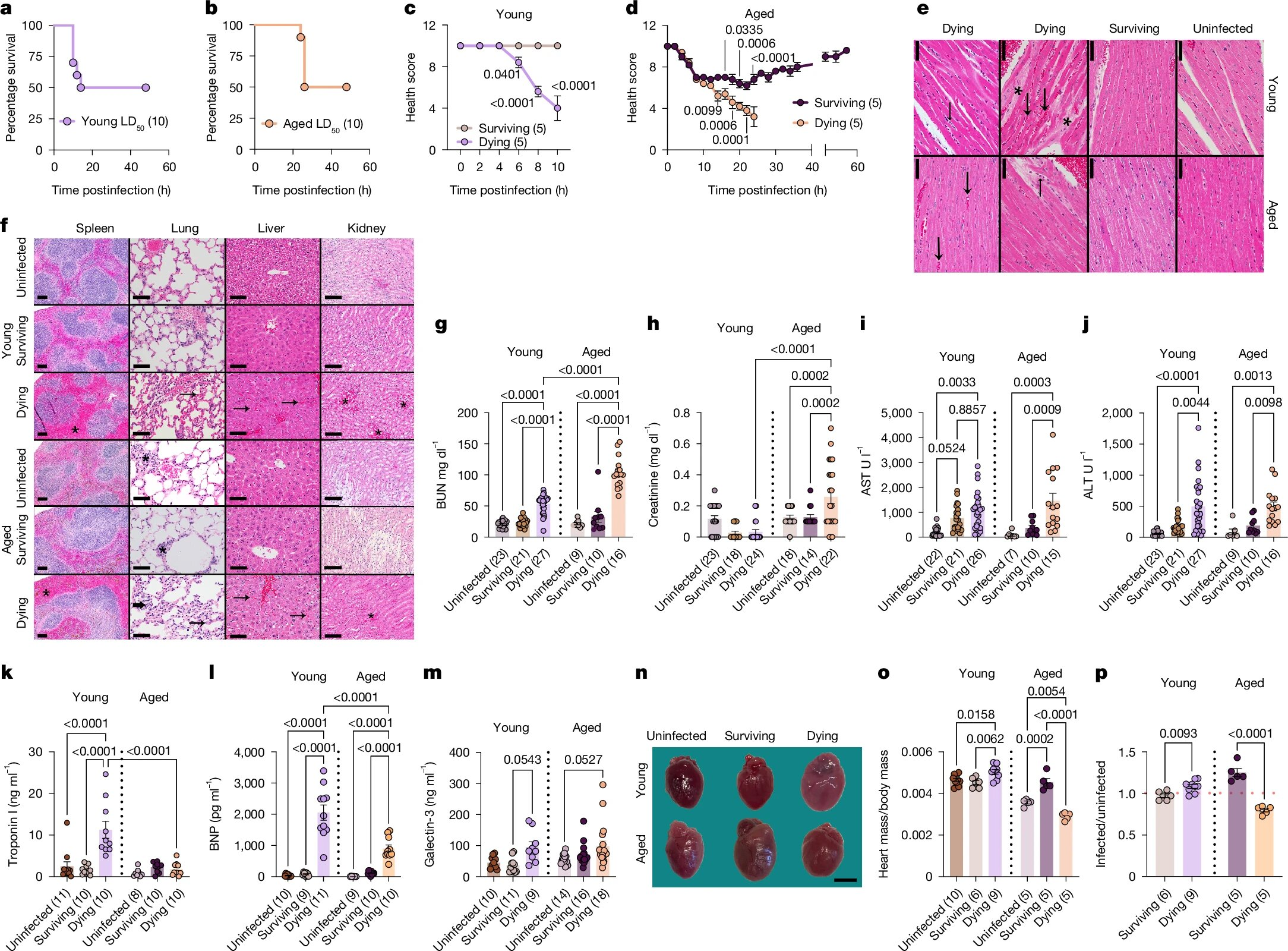

To study disease tolerance rather than just infection severity, the team used a method called LD50 dosing, a strategy developed by Ayres’ lab in 2018. This approach exposes animals to a dose of infection that is lethal to roughly half the population, allowing researchers to directly compare survivors and non-survivors under the same conditions.

This setup made it possible to observe not just whether the mice lived or died, but how their bodies responded at the molecular and organ level.

Two Ages, Two Very Different Disease Trajectories

One of the first striking observations was that young mice that did not survive sepsis died more quickly than older mice that did not survive. This indicated that aging alters the course of disease progression itself.

The differences became even more dramatic when researchers examined the mice that survived. In young survivors, protection against multi-organ damage depended on a specific molecular pathway involving the protein Foxo1, the gene Trim63, and the protein MuRF1.

In young mice, Foxo1 activated Trim63, which increased MuRF1 production. MuRF1 helped break down large molecules into usable energy in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. This process turned out to be cardioprotective, preventing heart damage and reducing the risk of organ failure.

However, in older mice, the exact same pathway had the opposite effect.

When Protective Mechanisms Become Harmful

In aged mice, Foxo1, Trim63, and MuRF1 contributed to worse outcomes rather than protection. Deleting Foxo1 improved survival in older mice but reduced survival in young mice. Even among aged survivors, the researchers observed enlarged hearts and signs of cardiac remodeling, indicating long-term damage.

In other words, the mechanisms that helped young mice survive sepsis actively harmed older mice. This finding challenges the assumption that beneficial immune or metabolic pathways can be universally targeted across age groups.

The study demonstrates that the same molecular pathway can determine survival in both young and old hosts, but with completely opposite results.

Antagonistic Pleiotropy and Aging Biology

These findings fit well with the concept of antagonistic pleiotropy, a theory from evolutionary biology. The idea is that some biological traits provide strong benefits early in life, particularly during reproductive years, but carry hidden costs that emerge later.

From an evolutionary perspective, survival and reproduction in youth are prioritized, even if those same mechanisms increase vulnerability in old age. The Foxo1–Trim63–MuRF1 pathway appears to be a clear example of this principle in action.

Importantly, the researchers emphasize that aging does not mean the body loses its ability to tolerate disease. Instead, older individuals rely on different tolerance strategies, many of which have yet to be fully identified.

Why Antibiotic Resistance Makes This Research Urgent

The implications of this work extend far beyond sepsis alone. Antibiotic resistance is now considered one of the top ten global threats to humanity by the World Health Organization. Deaths linked to resistant infections now exceed those caused by HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined.

Because pathogens can evolve resistance to drugs that target them directly, researchers are increasingly interested in host-directed therapies. Disease tolerance strategies are especially attractive because pathogens cannot easily evolve resistance to treatments that target the host’s own physiological responses.

However, this study makes it clear that such therapies cannot be one-size-fits-all.

Toward Age-Specific Therapies for Infection

The findings suggest that future treatments for sepsis and other severe infections may need to be tailored by age, targeting different disease tolerance mechanisms in younger and older patients. Instead of suppressing the immune system broadly or relying solely on antibiotics, clinicians may eventually modulate specific metabolic or protective pathways based on a patient’s biological stage of life.

This approach could improve survival, reduce long-term organ damage, and help address the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. It also raises broader questions about how age influences disease outcomes in conditions ranging from viral infections to inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

Disease Tolerance Beyond Sepsis

While this study focused on sepsis in mice, disease tolerance plays a role in many other conditions. Chronic infections, inflammatory diseases, cancer, and even aging itself involve trade-offs between immune activity and tissue protection. Understanding how tolerance mechanisms shift over time could reshape how medicine approaches treatment across the lifespan.

The research highlights a future where precision medicine is not just about genetics or pathogens, but also about age-specific physiology.

Research reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09923-x