How a Unique Class of Neurons May Set the Table for Brain Development

The way the brain develops in early life has long-lasting effects on how we see, think, learn, and adapt to the world. Because of this, neuroscientists are deeply interested in understanding not just what develops in the brain, but how and when it happens. A recent study from researchers at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT sheds new light on this question by focusing on a very specific, and surprisingly independent, group of brain cells.

The research looks at a special class of inhibitory neurons known as somatostatin-expressing neurons, or SST neurons, and reveals that they follow a developmental rulebook quite different from most other neurons in the brain. Rather than being shaped by sensory experience, these neurons appear to develop on a largely experience-independent timeline, potentially laying the groundwork for how other brain circuits later adapt and refine themselves.

Excitation, Inhibition, and the Developing Brain

During early brain development, especially in regions like the visual cortex, multiple types of neurons emerge and begin forming connections. Broadly speaking, neurons fall into two functional categories: excitatory neurons, which increase activity in brain circuits, and inhibitory neurons, which regulate and restrain that activity.

A healthy brain relies on a precise balance between excitation and inhibition. Too much excitation can lead to instability, while too much inhibition can suppress learning and flexibility. This balance is particularly important during a developmental phase known as the critical period, which occurs shortly after the eyes open in young mammals. During this window, the visual cortex rapidly adjusts its wiring in response to incoming sensory information, refining millions of synaptic connections.

Most previous research has shown that both excitatory neurons and certain inhibitory neurons, such as parvalbumin-expressing cells, are strongly influenced by visual experience during this time. Altering sensory input, for example by raising animals in darkness, can significantly change how these neurons develop. The new MIT study shows that SST neurons are a striking exception.

Tracking SST Neurons in Unprecedented Detail

To understand how SST neurons behave during development, the research team, led by Josiah Boivin and Elly Nedivi, closely examined how these cells form synapses with excitatory neurons in the mouse visual cortex. SST neurons connect to excitatory cells through small structures called boutons, which serve as the physical points of synaptic contact.

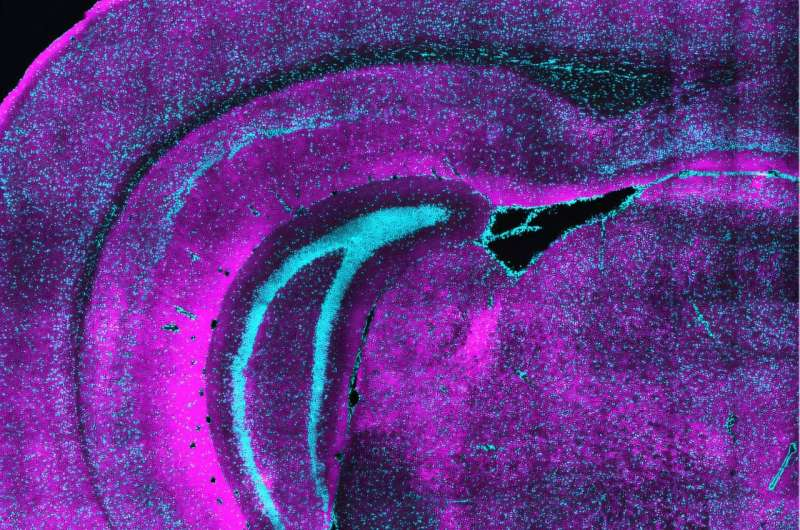

The team used a combination of advanced genetic labeling techniques and a powerful imaging method known as eMAP (epitope-preserving magnified analysis of proteome). This technique expands and clears brain tissue, allowing researchers to visualize synapses at extremely high resolution across large sections of the brain. With this approach, the scientists were able to follow SST bouton formation and synapse development before, during, and after the critical period in remarkable detail.

What they found was unexpected.

A Developmental Path Unaffected by Experience

SST bouton formation surged around the time of eye opening and continued as the critical period began. However, unlike other neuron types, SST neurons did not follow the typical developmental pattern of the cortex. While excitatory neurons mature in a layered sequence, starting in deeper layers and progressing upward, SST boutons appeared across all cortical layers at the same time.

Even more surprising was what happened when sensory experience was manipulated. When mice were raised in darkness for varying lengths of time, the development of SST boutons and synapses remained unchanged. Visual deprivation, which strongly affects other neurons, had no detectable effect on SST neuron development.

This finding suggests that SST neurons are guided not by sensory input, but by genetic programs or age-dependent molecular signals. In other words, their development seems to be pre-scheduled rather than experience-driven.

No Pruning, No Rollback

Another hallmark of early brain development is synaptic pruning. After an initial burst of connection formation, many synapses are eliminated, leaving behind only those that are most useful for efficient sensory processing. This process helps fine-tune brain circuits.

Once again, SST neurons stood apart. While the pace of new SST synapse formation slowed during the peak of the critical period, the overall number of SST synapses never declined. There was no large-scale pruning. In fact, SST synapse numbers continued to increase gradually into adulthood.

This behavior sharply contrasts with excitatory synapses, many of which are removed as development progresses. The findings highlight that inhibition does not simply mirror excitation with an opposite effect, but instead follows its own distinct set of developmental rules.

Preparing the Brain for Plasticity

Why would the brain rely on a group of neurons that seems largely indifferent to experience during such a critical time? The researchers propose an intriguing explanation.

SST neurons may act as early stabilizers, establishing a baseline level of inhibition across the cortex. By doing so, they may create the right conditions for experience-dependent neurons to respond selectively to meaningful sensory input. Rather than directly shaping circuits, SST neurons might set the stage, ensuring that only certain patterns of activity trigger long-lasting changes.

As the brain matures, the continued growth of SST-mediated inhibition may also help explain why the adult brain remains capable of learning, but with less dramatic flexibility than during early childhood.

Why This Matters Beyond the Visual Cortex

Although this study focused on the visual cortex, its implications extend far beyond vision. The balance between excitation and inhibition is a core feature of brain function, and disruptions to this balance are linked to neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and epilepsy.

The imaging and labeling techniques used in this research make it possible to compare normal brain development with animal models of these conditions, potentially revealing where and how inhibitory circuits go awry. The same methods can also be applied to other brain regions, helping scientists understand how different cell types interact across the brain.

What Are SST Neurons, Exactly?

SST neurons are one of several major classes of inhibitory interneurons in the cortex. They typically target the dendrites of excitatory neurons, where they can fine-tune how incoming signals are integrated. This positioning gives them a powerful role in controlling how information flows through neural circuits.

Importantly, SST neurons are not a single uniform population. They include multiple subtypes with different molecular signatures and functional roles. Understanding how these subtypes develop may be key to explaining how complex brain networks remain both stable and adaptable.

Looking Ahead

For Josiah Boivin, who is moving on to start his own laboratory, the findings open up new avenues for studying inhibitory synapse formation in other brain systems, including limbic regions involved in emotion and adolescent mental health. For the broader neuroscience community, the work underscores a growing realization: inhibition is not just a counterbalance to excitation, but a dynamic and independent force in brain development.

By revealing that SST neurons follow their own developmental logic, this study adds an important piece to the puzzle of how the brain builds itself—and why early life is such a crucial window for shaping who we become.

Research paper:

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/early/2026/01/12/JNEUROSCI.1870-25.2026