How a Cellular Quality-Control Protein Can Trigger Neurodegenerative Disease

Neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and certain forms of dementia have long puzzled scientists. While researchers have known for years that problems with protein quality control and damage to the nuclear pore are central features of these conditions, the precise connection between the two has remained unclear. Now, a new study from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, published in the journal Neuron, provides a detailed explanation of how these processes are linked—and why a protein meant to protect cells can end up causing serious harm when it becomes overactive.

At the center of this discovery is a protein called valosin-containing protein (VCP), a molecule found in nearly all living organisms, from yeast to humans. The study shows that when VCP’s normal “cleanup” role goes into overdrive, it can destabilize one of the cell’s most critical structures, ultimately contributing to neurodegeneration.

Understanding the Nuclear Pore and Why It Matters

The nuclear pore complex is one of the largest and most intricate protein assemblies in the cell. Built from roughly 30 different proteins, it forms a highly regulated gateway that controls the movement of proteins and RNA between the nucleus, where genetic information is stored and processed, and the cytoplasm, where much of the cell’s work is carried out.

This transport system is not optional—it is essential for normal cellular function. Neurons, in particular, are extremely sensitive to disruptions in nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking. Over the past decade, researchers have repeatedly observed that the nuclear pore behaves abnormally in many neurodegenerative diseases.

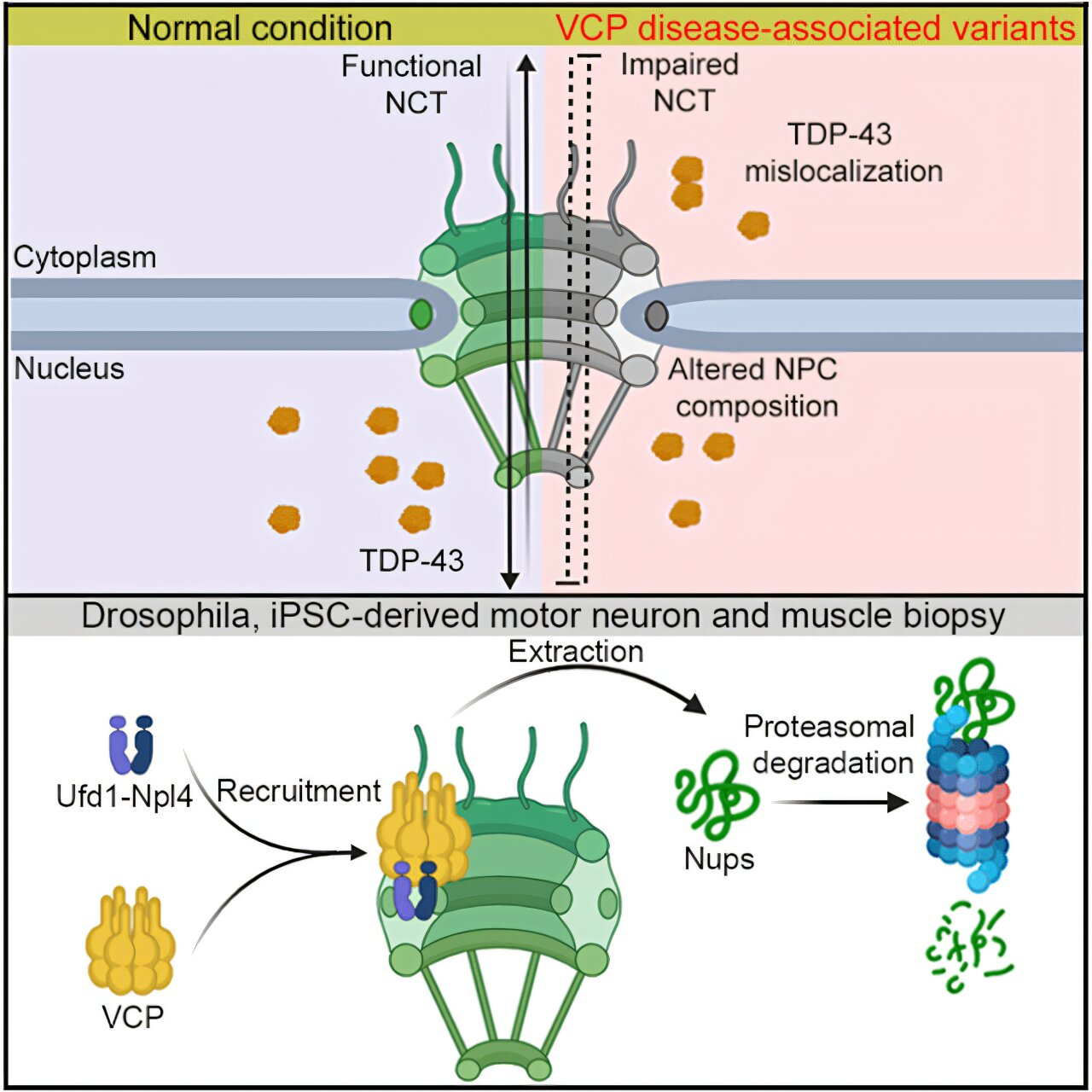

One of the most consistent warning signs involves a protein called TDP-43. Under healthy conditions, TDP-43 spends most of its time in the nucleus, where it helps regulate RNA processing. In ALS and several dementias, however, TDP-43 is lost from the nucleus and begins to accumulate in the cytoplasm, forming toxic aggregates. This leads to a double problem: neurons lose TDP-43’s normal nuclear function while also gaining harmful protein clumps in the cytoplasm.

What has been missing until now is a clear explanation of why the nuclear pore breaks down in the first place—and how TDP-43 ends up in the wrong part of the cell.

VCP: A Cellular Cleanup Crew With a Dark Side

The new research identifies VCP as a central player in this process. VCP is a powerful protein quality-control factor. Its normal job is to recognize damaged or misfolded proteins, extract them from cellular structures, and send them to the cell’s degradation systems. In this way, VCP acts like a molecular cleanup crew, preventing harmful protein buildup.

Importantly, VCP activity must be carefully balanced. Too little activity allows damaged proteins to accumulate, which is known to contribute to several neurodegenerative conditions. But this study highlights a less appreciated danger: too much VCP activity.

In certain inherited neurodegenerative disorders collectively referred to as VCP disease, researchers found that VCP becomes excessively active. Instead of selectively removing damaged proteins, overactive VCP begins to prematurely extract healthy components of the nuclear pore complex. Once removed, these critical nuclear pore proteins are sent for degradation, even though they are still needed.

The result is a destabilized and dysfunctional nuclear pore. When the pore can no longer regulate traffic properly, proteins like TDP-43 fail to stay in the nucleus and instead drift into the cytoplasm, where they form toxic aggregates that damage neurons.

Evidence Across Multiple Model Systems

One of the strengths of this study is how broadly the researchers tested their findings. The same destructive mechanism was observed across multiple experimental systems, including fruit flies, animal models, and human-derived neurons grown in the lab. This consistency strongly suggests that the link between overactive VCP, nuclear pore degradation, and neurodegeneration is not limited to a single species or model.

Even more compelling, the researchers showed that partially inhibiting VCP activity could reverse some of the damage. In animal models of VCP disease, reducing VCP activity helped restore nuclear pore integrity and improved physical function, such as climbing ability in flies. These results provide some of the first in vivo evidence that excessive VCP activity—not a lack of it—is a direct cause of disease, and that carefully dialing it back can be beneficial.

Why This Matters for Future Treatments

These findings open up new possibilities for treating neurodegenerative disease, but they also highlight the complexity of the challenge. VCP is involved in many essential cellular processes, including protein degradation, organelle maintenance, and stress responses. Because of this, broadly blocking VCP is not an option.

Some VCP inhibitors already exist and are currently used in cancer research and treatment. However, neurodegenerative diseases require a much more precise approach. Researchers now believe the key will be understanding how VCP interacts with specific adaptor proteins that guide it to the nuclear pore. Targeting those interactions—rather than shutting down VCP entirely—could allow scientists to protect the nuclear pore while preserving the protein’s essential housekeeping roles.

This work also reinforces a broader idea in neurodegeneration research: protein degradation is a double-edged sword. Insufficient degradation leads to toxic protein accumulation, while excessive degradation can destroy structures that cells depend on to survive.

Additional Context: Protein Quality Control in Neurodegeneration

Protein quality control has emerged as one of the most important themes in modern neuroscience. Neurons are long-lived cells that rarely divide, meaning they must maintain their internal components for decades. Systems like ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, autophagy, and VCP-mediated extraction are essential for this long-term survival.

When any part of this network becomes unbalanced, neurons are often among the first cells to suffer. The new findings add the nuclear pore complex to a growing list of vulnerable structures affected by proteostasis failure. They also help explain why disruptions in nuclear-cytoplasmic transport appear in so many different neurodegenerative diseases, from ALS to frontotemporal dementia.

A Clearer Picture of Disease Mechanisms

Taken together, this research provides a clearer, more complete picture of how a protein designed to protect cells can become a driver of disease. By showing that overactive VCP directly degrades nuclear pore components, leading to TDP-43 mislocalization and neuronal damage, the study fills in a major gap in our understanding of neurodegeneration.

It also shifts the conversation away from simple “loss-of-function” explanations and toward a more nuanced view in which excessive activity can be just as harmful. As researchers continue to explore how protein quality control systems interact with critical cellular structures, studies like this one offer hope that more targeted and effective therapies may eventually emerge.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.11.017