Across Cultures, People Combine Reference Frames to Navigate and Understand Space

When people move through the world—walking through a new city, arranging objects on a table, or simply giving directions—they rely on mental systems that help them understand where things are. A recent study published in Psychological Science (2025) shows that humans across very different cultures don’t rely on just one of these systems. Instead, they often combine multiple reference frames at the same time, revealing something fundamental about how the human mind handles space.

Understanding How Humans Use Reference Frames

To orient ourselves, we typically rely on reference frames, which are ways of describing and remembering locations. Broadly speaking, there are two main types.

The first is the egocentric reference frame, which is centered on the body. Directions like left, right, in front of you, or behind you fall into this category. These references change as the body turns or moves.

The second is the allocentric reference frame, which is based on the environment. These references stay stable regardless of where the body is positioned. For example, something can be described as being next to a window, near a tree, or on the east side of a room.

Both systems are useful, but they operate differently. If you turn around, your left and right switch, but the window stays exactly where it was. For decades, researchers have debated whether people rely primarily on one system or the other—and whether culture plays a decisive role in shaping this preference.

Culture, Language, and the Way We Talk About Space

Cultural background has long been thought to influence how people describe and think about space. In many Western societies, including the United States, people tend to favor body-based descriptions. Saying something is “on your left” or “behind you” feels natural and automatic.

In contrast, some Indigenous cultures regularly use environment-based references. In these communities, people may describe locations using landmarks, river directions, or cardinal points like north, south, east, and west. Rather than saying something is on your left, it might be described as being upriver or toward the sunrise.

This difference is not just linguistic. The physical environment also matters. In dense forests or river-based regions, tracking environmental features can be far more useful than keeping track of left and right, which can easily become confusing as the body moves.

Earlier Research Raised an Important Question

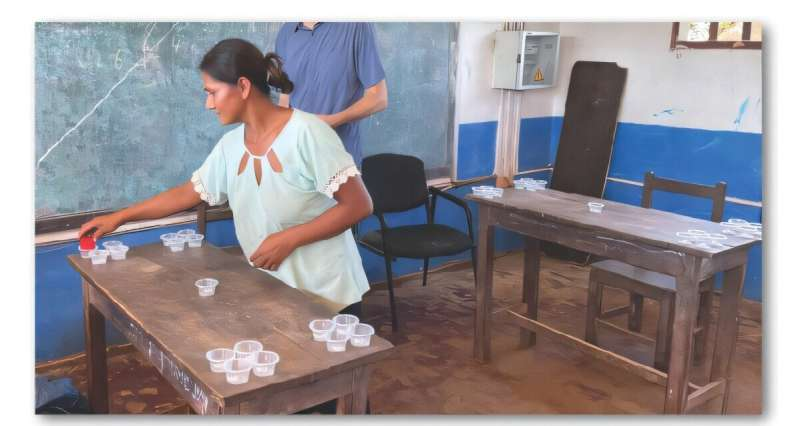

In a 2022 study published in Science Advances, researcher Benjamin Pitt and his colleagues studied the Indigenous Tsimane’ people of Bolivia. They found that the Tsimane’ used allocentric reference frames when organizing objects along a left–right axis, but relied on egocentric reference frames when arranging objects front to back.

This raised a deeper question. Were people rapidly switching between reference frames depending on the task? Or could they actually use both reference frames simultaneously?

That question became the focus of Pitt’s 2025 study.

The 4Quads Task Explained

To investigate this, researchers designed an experiment known as the 4Quads task. Participants included both Tsimane’ adults and adults from the United States.

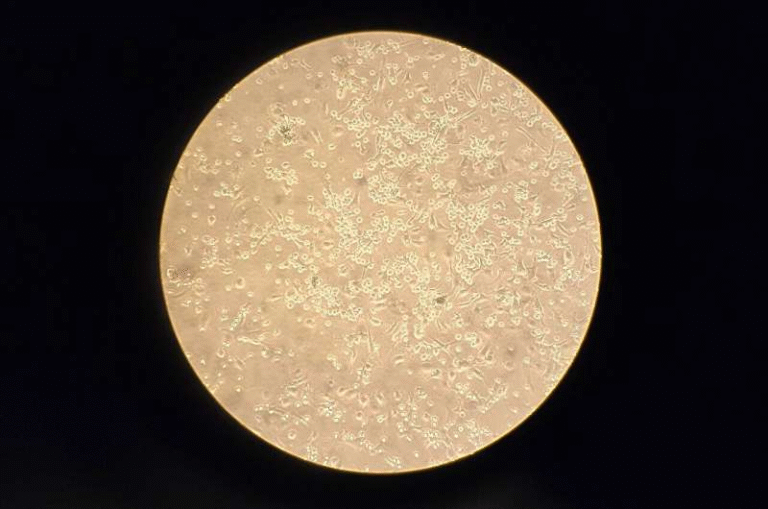

Each participant was shown a rectangular table with four cups placed at its corners. A small ball was placed in one of these cups. The participant’s task was simple but revealing: they were asked to pick up the ball, turn 180 degrees, face an identical table arranged in the same way, and then place the ball in the “same” cup.

Participants repeated this process across 16 trials.

What made the task powerful was that different strategies led to different answers. If someone relied purely on egocentric references, they would place the ball based on their body perspective—such as far right or near left—regardless of environmental features.

If someone relied purely on allocentric references, they would place the ball based on features of the room, such as proximity to a window or door.

The setup allowed researchers to analyze not just whether participants used one reference frame or the other, but which reference frame they used along different spatial axes.

A Surprising and Consistent Pattern

The results showed a striking pattern across cultures.

Both U.S. participants and Tsimane’ participants used environment-based (allocentric) references to determine left–right positioning. At the same time, they used body-based (egocentric) references to determine front–back positioning.

In other words, participants were not switching between systems from one trial to the next. They were integrating two reference frames within a single action.

This finding strongly suggests that the human brain is capable of building what researchers call compound cognitive maps, combining multiple spatial systems at once.

Why Left and Right Are Special

One of the most interesting insights from the study relates to why this division might exist.

Left–right distinctions are cognitively harder for humans than front–back distinctions. People frequently confuse left and right, even in everyday situations, while almost no one confuses front with back.

Because left and right are less stable and more prone to error, people may abandon body-based references for that axis and instead rely on stable environmental cues. Using landmarks or fixed features removes the need to track shifting body orientation.

Front–back distinctions, on the other hand, are tightly linked to how our bodies move through space. Since we almost always move forward and perceive the world from the front, egocentric references remain reliable along this axis.

What This Tells Us About Human Cognition

The findings challenge the idea that cultures rely exclusively on one spatial system. Instead, they point to a more flexible and universal cognitive strategy.

Regardless of language, environment, or cultural background, humans appear to blend reference frames in practical ways. This integration allows people to move efficiently, remember object locations, and adapt to complex environments.

Rather than thinking of egocentric and allocentric systems as competing, this research suggests they work together, each handling the aspects of space they are best suited for.

Broader Implications Beyond Navigation

Understanding how people combine reference frames has implications beyond basic navigation.

In neuroscience, it helps explain how different brain regions involved in spatial memory and perception interact. In psychology, it sheds light on how perception, language, and action are coordinated.

There are also practical applications in areas like robotics, virtual reality, and user-interface design, where systems need to mirror how humans naturally think about space.

Even in education, understanding spatial cognition can help improve teaching methods in geometry, geography, and STEM fields that rely heavily on spatial reasoning.

A More Unified View of Human Spatial Thinking

The key takeaway from this research is simple but powerful: humans don’t rely on a single way of understanding space. Instead, we dynamically integrate multiple reference frames depending on what works best for the situation.

Whether navigating a rainforest river, crossing a city street, or placing a ball on a table, people across cultures use a shared cognitive strategy that balances the body and the environment.

This ability to combine perspectives may be one of the reasons humans are so adaptable in navigating the world.

Research reference:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09567976251391172