Molecular Switch That Turns On Inflammation in Obesity Points to New Therapeutic Targets

Obesity has long been linked to chronic, low-grade inflammation, but exactly how excess body fat flips the body into an inflammatory state has remained a major unanswered question. A new study led by researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center now offers a detailed, molecular-level explanation—and in doing so, highlights several promising new therapeutic targets that could one day help reduce obesity-related diseases.

The research, published in Science, identifies a previously unknown molecular “switch” that becomes activated in obesity and sets off widespread inflammation. This discovery helps explain why obesity increases the risk of conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, and certain cancers, even in the absence of infection.

Why inflammation matters in obesity

Globally, nearly 900 million adults—about one in eight people—live with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. One of the most damaging features of obesity is persistent sterile inflammation, meaning inflammation that occurs without bacteria or viruses. Over time, this ongoing immune activation disrupts metabolism, damages tissues, and accelerates chronic disease.

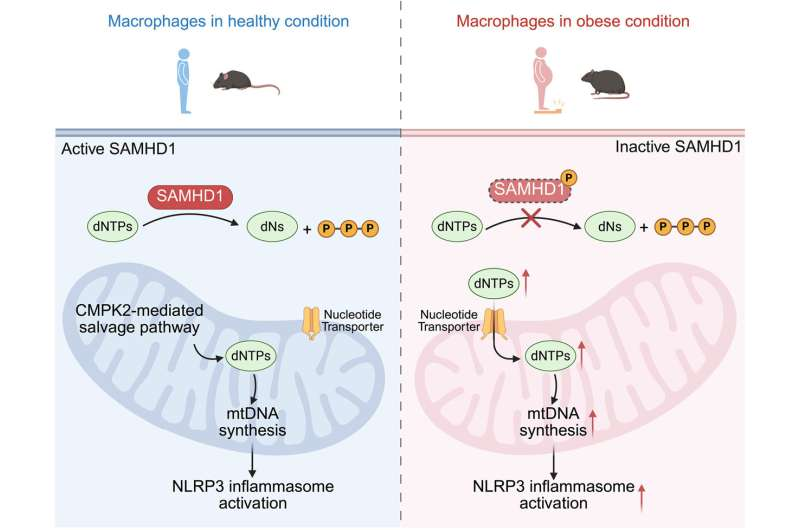

At the center of this inflammatory response is a protein complex called the NLRP3 inflammasome, which operates inside immune cells known as macrophages. When activated, NLRP3 converts inactive inflammatory molecules into active cytokines, such as IL-1β, which then spread inflammation throughout the body. While NLRP3 has been known to drive obesity-related inflammation, what actually triggers its hyperactivation in obesity has remained unclear—until now.

Comparing lean and obese immune cells

To uncover the mechanism, the researchers compared macrophages from lean and obese human volunteers, as well as from mice fed either a normal diet or a high-fat diet. Across both humans and mice, macrophages associated with obesity showed markedly higher NLRP3 activity, confirming that obesity pushes immune cells into an overactive inflammatory state.

One of the most striking findings was the presence of abnormally high levels of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in macrophages from obese subjects. Mitochondria—the cell’s energy-producing structures—have their own DNA, and under normal conditions, mtDNA levels are tightly regulated. In obesity, however, not only was mtDNA increased, but much of it was oxidized, a damaged form that commonly appears under cellular stress.

Crucially, when the researchers blocked the ability of oxidized mitochondrial DNA to interact with the NLRP3 inflammasome, the excessive inflammasome activation stopped. This result directly linked damaged mtDNA to the inflammatory response seen in obesity.

The unexpected role of DNA building blocks

To understand why obese macrophages were producing so much mitochondrial DNA, the team looked deeper into the cells’ biochemistry. They discovered an accumulation of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) in the cytoplasm. dNTPs are the basic building blocks of DNA, and their levels are normally kept under tight control.

The buildup of these DNA components pointed to a malfunction in SAMHD1, an enzyme responsible for degrading excess dNTPs. In macrophages from obese humans and high-fat-diet mice, SAMHD1 was found to be phosphorylated, a chemical modification that effectively turns off its enzymatic activity.

With SAMHD1 disabled, excess dNTPs accumulated in the cytoplasm and were then transported into mitochondria. This fueled uncontrolled mitochondrial DNA synthesis, leading to increased production of oxidized mtDNA—the very signal that hyperactivates the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Proving the mechanism across species

To confirm that SAMHD1 was truly central to this process, the researchers genetically deleted the SAMHD1 gene in mice and even in zebrafish, a species that shares about 70% of its genes with humans. In both animals, the absence of SAMHD1 triggered the same chain of events: elevated cytoplasmic dNTPs, excess oxidized mtDNA, and hyperactive NLRP3 inflammasomes.

These changes had serious physiological consequences. Many of the affected mice developed type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease, demonstrating that this molecular switch doesn’t just alter immune cells—it drives whole-body metabolic disease.

Importantly, restoring normal SAMHD1 activity—or blocking the downstream steps of the pathway—prevented these inflammatory effects, reinforcing the idea that this enzyme acts as a critical gatekeeper of inflammation.

How this fits with earlier research

This study builds on earlier work by the same research group, which identified the mitochondrial enzyme CMPK2 as essential for mtDNA production and NLRP3 activation in lean, healthy individuals. The new findings reveal that obesity bypasses this normal pathway, instead rewiring nucleotide metabolism to sustain inflammation even in the absence of infection or injury.

In other words, obesity doesn’t just increase inflammation—it fundamentally alters how immune cells manage DNA metabolism, pushing them into a chronic inflammatory state.

New therapeutic possibilities

By mapping this pathway step by step, the study highlights several potential intervention points. These include finding ways to:

- Prevent or reverse SAMHD1 phosphorylation, restoring its ability to clear excess dNTPs

- Block the transport of dNTPs into mitochondria, stopping abnormal mtDNA synthesis

- Disrupt the interaction between oxidized mtDNA and the NLRP3 inflammasome, preventing inflammasome hyperactivation

Any of these strategies could, in theory, reduce inflammation and lower the risk of obesity-related diseases. While such treatments are still far from clinical use, the study provides a clear molecular blueprint for future drug development.

Why this discovery is important

What makes this research especially significant is its ability to connect metabolism, mitochondrial biology, and immune signaling into a single, coherent mechanism. For years, obesity-related inflammation has been recognized as a major driver of disease, but without a clear molecular explanation. This study finally fills that gap.

By identifying a precise molecular switch that turns inflammation on in obesity, the findings open the door to therapies that target inflammation without broadly suppressing the immune system—a key challenge in current anti-inflammatory treatments.

As obesity rates continue to rise worldwide, understanding and controlling the inflammatory processes that accompany excess weight may prove just as important as managing diet and physical activity. This research brings scientists one step closer to that goal.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq9006