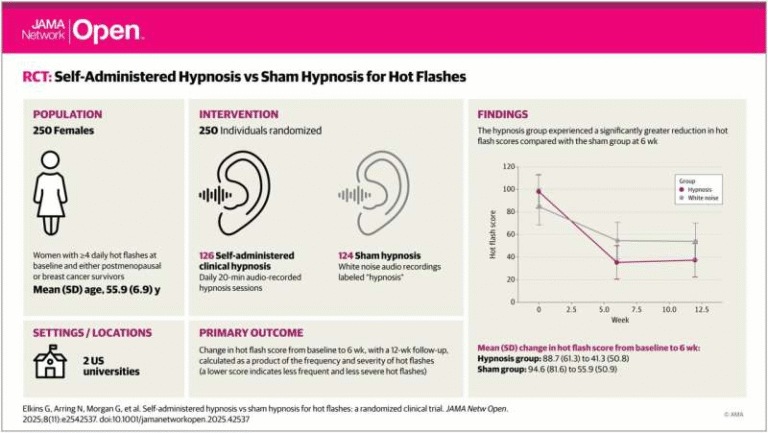

Potential New Target to Treat Parkinson’s Disease Discovered by Case Western Reserve University Researchers

Parkinson’s disease affects around 1 million people in the United States, with nearly 90,000 new cases diagnosed every year, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation. It is a chronic, progressive neurological disorder that gradually damages dopamine-producing neurons in the brain—cells that are essential for smooth, coordinated movement, balance, and motor control. While existing treatments can help manage symptoms such as tremors and stiffness, they do little to stop or slow the underlying disease process.

Now, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have uncovered a promising new direction that could eventually change how Parkinson’s disease is treated. Their work identifies a previously unrecognized molecular interaction that contributes directly to neuron damage and offers a targeted way to disrupt it. The findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal Molecular Neurodegeneration.

A closer look at what goes wrong inside brain cells

At the center of this discovery is alpha-synuclein, a protein long associated with Parkinson’s disease. In healthy brains, alpha-synuclein plays a role in normal neuron function. In Parkinson’s, however, this protein misfolds and accumulates into toxic aggregates, forming one of the disease’s defining pathological features.

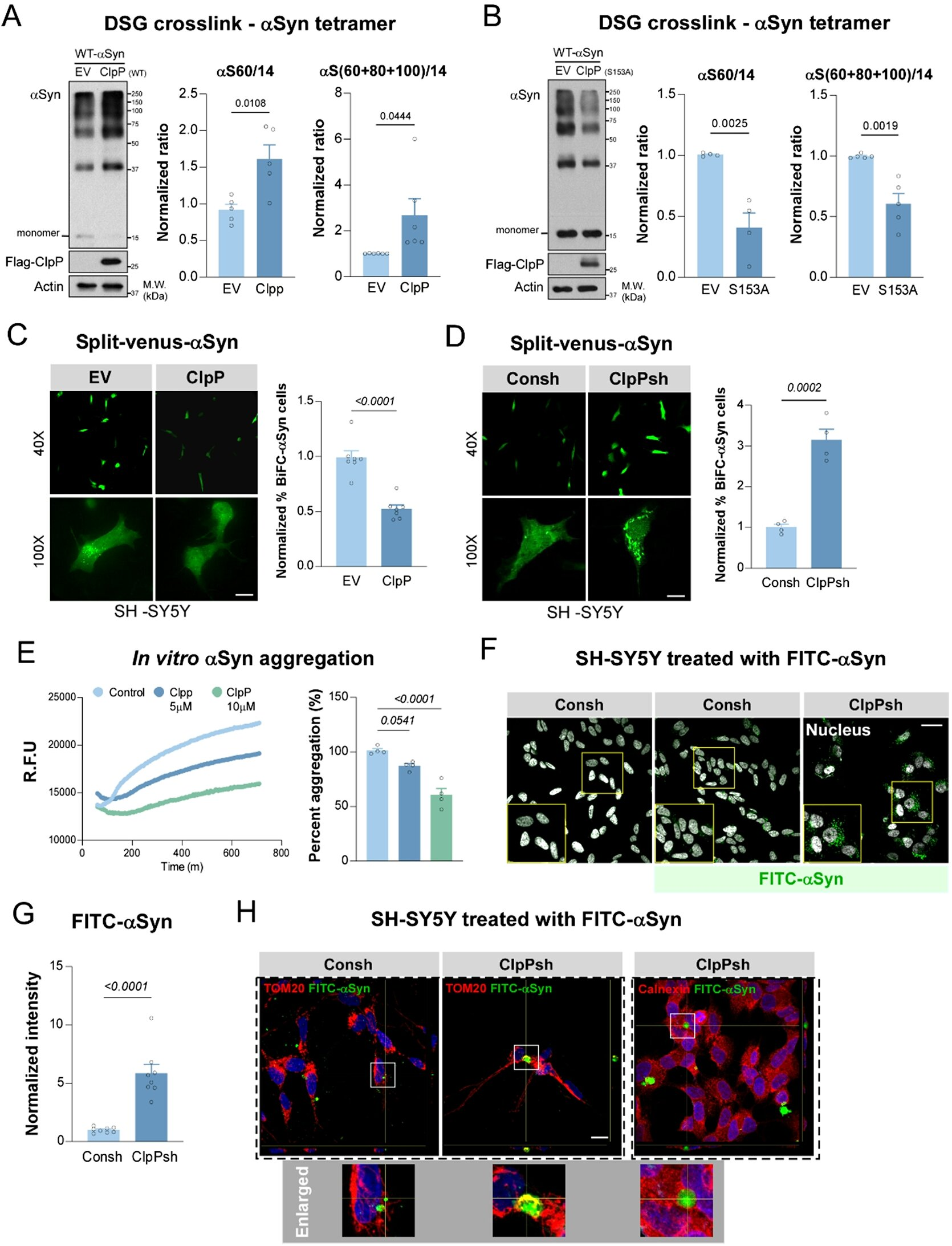

The Case Western Reserve team found that alpha-synuclein does more than just clump together. It inappropriately interacts with an essential mitochondrial enzyme called ClpP. ClpP normally supports mitochondrial quality control, helping maintain the health of mitochondria—the energy-producing structures of cells.

When alpha-synuclein binds to ClpP in the wrong way, this protective system breaks down. The mitochondria become damaged, energy production falters, and neurons—especially dopamine-producing ones—begin to die. This mitochondrial failure is a critical driver of neurodegeneration, and the researchers observed that this harmful interaction also accelerates disease progression in multiple experimental models.

Why mitochondria matter so much in Parkinson’s disease

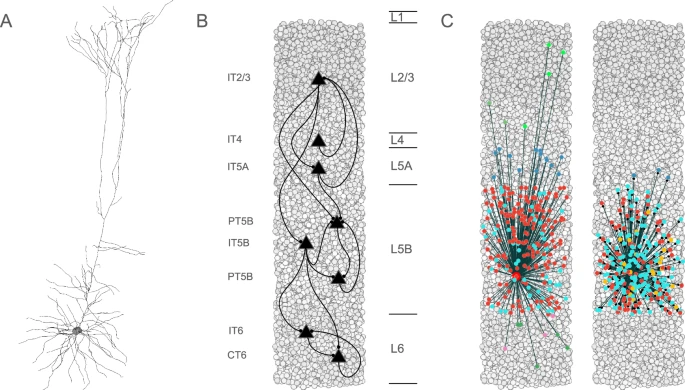

Mitochondria are often described as the cell’s power plants, and neurons are particularly dependent on them because of their high energy demands. Dopaminergic neurons, the type most affected in Parkinson’s disease, are especially vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Decades of research have linked Parkinson’s disease to mitochondrial damage, but targeting this damage therapeutically has been challenging. This study provides a clear biochemical pathway explaining how mitochondrial failure can be triggered by toxic protein interactions, offering a more precise target for intervention.

The development of CS2, a targeted experimental therapy

Building on this discovery, the research team designed a molecule known as CS2. Rather than trying to remove alpha-synuclein entirely, CS2 works by blocking its harmful interaction with ClpP.

CS2 acts as a decoy, binding to alpha-synuclein and preventing it from attaching to ClpP. By doing so, it protects mitochondrial function and allows the cell’s energy systems to recover. Importantly, this approach does not interfere with the normal roles of either protein, which has been a major obstacle in past therapeutic strategies.

In laboratory testing, CS2 showed encouraging results across a wide range of models. These included human brain tissue, neurons derived from Parkinson’s disease patients, and mouse models that replicate key features of the disease.

Improvements seen in multiple disease models

Across these experimental systems, treatment with CS2 led to several notable improvements. Mitochondrial function was restored, harmful protein accumulation was reduced, and markers of brain inflammation decreased. In animal models, these cellular improvements translated into better motor function and cognitive performance, suggesting that protecting mitochondria can have meaningful effects on behavior and brain health.

These findings are significant because they demonstrate benefits not just at the molecular level, but also in whole organisms. That kind of consistency is essential when evaluating whether a potential therapy is worth advancing toward human trials.

A shift from symptom relief to targeting root causes

Most current Parkinson’s treatments focus on replacing or mimicking dopamine to temporarily improve movement symptoms. While effective in the short term, these therapies do not prevent neurons from continuing to degenerate.

This new approach represents a fundamentally different strategy. By targeting a mechanism that directly contributes to neuron death, the research aims to intervene at one of the root causes of the disease, rather than simply masking its effects.

Why alpha-synuclein remains a major research focus

Alpha-synuclein has been a central focus in Parkinson’s research for years. Various strategies—including vaccines, antibodies, and aggregation inhibitors—have attempted to reduce its toxicity, with mixed success in clinical trials.

What makes this discovery stand out is its specificity. Instead of broadly targeting alpha-synuclein, it identifies a particular interaction that causes mitochondrial damage and shows how disrupting that interaction can be beneficial. This precision may help overcome some of the limitations seen in earlier approaches.

The role of interdisciplinary collaboration

The success of this research was made possible by long-standing interdisciplinary collaboration at Case Western Reserve University. Expertise in mitochondrial biology, neurodegenerative disease, and advanced disease-relevant model systems allowed the team to connect molecular findings to functional outcomes.

The university also has a strong track record of translating basic scientific discoveries into potential therapeutic strategies, which positions this research well for further development.

What comes next for this discovery

The researchers estimate that it could take up to five years to move this discovery closer to clinical trials. Several critical steps remain, including optimizing CS2 for human use, conducting extensive safety and efficacy testing, and identifying molecular biomarkers that can track disease progression and treatment response.

If these steps are successful, the approach could eventually be tested in people with Parkinson’s disease. While there is still a long road ahead, the findings provide a strong foundation for future translational research.

Broader implications for neurodegenerative diseases

Beyond Parkinson’s disease, this work reinforces the idea that toxic protein–mitochondria interactions may play a role in other neurodegenerative disorders as well. Understanding and targeting these interactions could open new therapeutic avenues across a range of conditions where mitochondrial dysfunction and protein aggregation overlap.

For now, this study adds an important piece to the Parkinson’s disease puzzle and highlights how deep molecular insights can lead to innovative treatment strategies with real potential to improve patients’ lives.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-025-00918-w