Noninvasive Brain Scanning Could Help Paralyzed People Send Signals to Their Limbs

People living with spinal cord injuries often face a frustrating reality: their brains and limbs may still be capable of working, but the communication pathway between them has been broken. The spinal cord, which acts as the body’s main signal highway, can no longer relay movement instructions from the brain to the muscles. Now, a new study suggests that noninvasive brain scanning technology might offer a way to reconnect those signals—without the need for risky brain surgery.

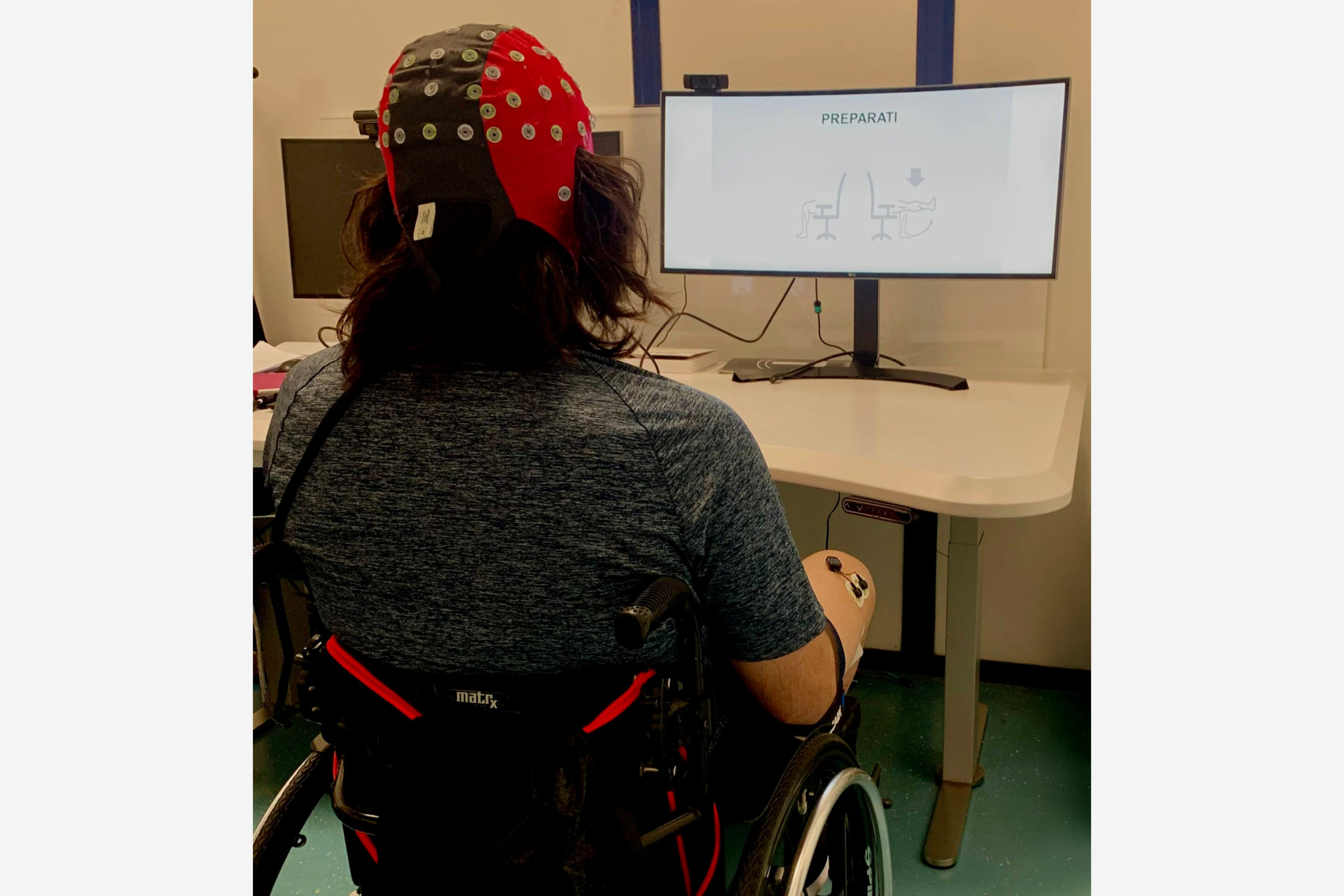

Researchers from universities in Italy and Switzerland have conducted an early feasibility study exploring whether electroencephalography (EEG) can be used to detect a patient’s intention to move a paralyzed limb and translate that intention into signals for a spinal cord stimulator. The work was published in the journal APL Bioengineering and focuses specifically on people with spinal cord injuries.

At the core of this research is a simple but powerful idea: when a person tries to move, their brain still generates the electrical patterns associated with that movement, even if the body cannot carry it out. If those patterns can be reliably read, decoded, and redirected, they could potentially be used to activate nerves below the injury and restore some level of voluntary control.

Why Spinal Cord Injuries Break the Brain–Body Connection

In many spinal cord injury patients, the problem is not the brain or the muscles themselves. The neurons in the brain that plan movement continue to function, and the nerves in the limbs are often still capable of responding. The issue lies in the damaged spinal cord, which blocks the signals traveling between the two.

Over the past decade, researchers have experimented with spinal cord stimulation, a technique that delivers electrical impulses to nerve networks below the injury. In some cases, stimulation has helped patients regain partial movement or improve muscle control. However, these systems usually rely on preprogrammed patterns or residual physical input rather than direct brain commands.

That’s where EEG-based brain signal decoding comes in.

Using EEG to Read Movement Intentions

EEG devices are typically worn as caps fitted with multiple electrodes that sit on the scalp and measure electrical activity produced by the brain. Unlike implanted electrodes, EEG does not require surgery, making it a safer and more accessible option for patients.

In this study, researchers equipped spinal cord injury patients with EEG monitors and asked them to attempt a series of simple lower-limb movements, such as moving their legs. Even though the patients could not physically perform these actions, their brains still produced recognizable electrical patterns associated with movement attempts.

The team collected these EEG signals and fed them into a machine learning algorithm designed to work with small and noisy datasets. The algorithm’s task was to determine whether it could reliably tell the difference between moments when a patient was attempting to move and moments when they were at rest.

The results were encouraging, though not perfect.

What the Researchers Found

The researchers were able to distinguish attempted movement from no movement using EEG data. This alone is an important milestone, as it confirms that noninvasive brain signals can capture meaningful information about motor intention in spinal cord injury patients.

However, the system struggled when it came to differentiating between specific types of movement. For example, telling apart one attempted movement from another—such as different leg actions—proved much more difficult.

This limitation is not entirely surprising. EEG electrodes sit on the surface of the scalp, which makes it harder to detect signals coming from deeper regions of the brain. Lower-limb movements are primarily controlled by areas located more centrally and deeper within the motor cortex, while upper-limb movements tend to be represented closer to the surface.

As a result, EEG works better for decoding arm and hand movements than for legs and feet, which present a tougher technical challenge.

Why Noninvasive Matters

Much of the previous research in this field has relied on implantable electrodes placed directly in the brain or spinal cord. While these systems can capture cleaner and more precise signals, they come with significant downsides, including surgical risks, infections, and long recovery times.

The researchers behind this study wanted to explore whether those risks could be avoided altogether. EEG, despite its limitations, offers a noninvasive alternative that could be easier to deploy in clinical settings and more acceptable to patients.

If EEG-based systems can be improved, they could potentially serve as a bridge between the brain and existing spinal cord stimulators—allowing stimulation to be driven by real-time brain intent rather than preset programs.

The Role of Machine Learning

A key part of this study was the use of machine learning algorithms tailored to work with EEG data. Brain signals are notoriously noisy, and EEG recordings often vary significantly between individuals. Advanced algorithms are essential for filtering out irrelevant activity and identifying consistent patterns linked to movement intention.

In this early study, the algorithm performed well enough to confirm feasibility, but the researchers acknowledge that significant improvements are needed before the system can be used in real-world rehabilitation.

Future versions of the algorithm may be trained to recognize more complex intentions, such as standing up, walking, or climbing stairs, rather than simply detecting whether a movement attempt is happening.

What This Could Mean for Patients

While this research is still in its early stages, it points toward a future where paralyzed patients could control their limbs more naturally, using their own brain signals instead of external controls.

In an ideal setup, a patient would wear an EEG cap that continuously monitors brain activity. When they attempt to move, the system would decode that intention and send corresponding signals to a spinal cord stimulator, which would then activate the appropriate muscles.

This kind of closed-loop system could make rehabilitation more intuitive and potentially more effective, especially when combined with physical therapy and neuroplasticity-based training.

Understanding EEG and Brain–Computer Interfaces

EEG is one of several approaches used in brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), systems that translate brain activity into commands for external devices. BCIs are already used in applications such as communication tools for people with severe paralysis and control systems for prosthetic limbs.

Noninvasive BCIs like EEG are generally easier to use and safer but offer lower signal resolution. Invasive BCIs provide more detailed data but require surgery. The challenge for researchers is finding the right balance between signal quality and patient safety.

This study adds to a growing body of evidence that noninvasive approaches, while imperfect, may still be powerful enough to support meaningful motor recovery.

Looking Ahead

The researchers emphasize that their findings represent a proof of concept, not a finished solution. Larger studies, better algorithms, and tighter integration with spinal cord stimulators will be necessary before this technology can move into clinical use.

Still, the idea that a simple EEG cap could one day help restore voluntary movement in people with spinal cord injuries is a compelling one. It suggests a future where brain-driven rehabilitation becomes more personalized, less invasive, and more closely aligned with how the nervous system naturally works.

As research continues, noninvasive brain scanning may play an increasingly important role in helping paralyzed patients reconnect with their own bodies—one decoded signal at a time.