Digital Technique Puts Rendered Fabric in the Best Light

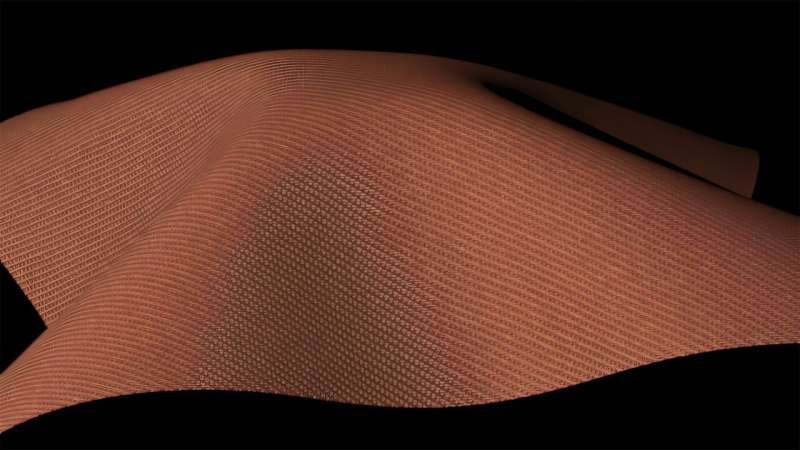

The sheen of satin, the soft glints of twill, and the delicate translucence of silk are things we instantly recognize in real life—but recreating them convincingly in digital images has long been one of the hardest challenges in computer graphics. Fabric doesn’t behave like metal, plastic, or skin. It bends, scatters, absorbs, and reflects light in complex ways that depend on its microscopic structure. Now, researchers at Cornell University, working in partnership with NVIDIA, have unveiled a new digital technique that significantly improves how fabric is rendered on screen, making cloth look far more realistic than ever before.

This new method was presented at SIGGRAPH Asia 2025 in Hong Kong, one of the world’s most important conferences for computer graphics and interactive techniques. The study comes from the lab of Steve Marschner, a professor of computer science at Cornell’s Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, who has been tackling fabric rendering problems for more than two decades.

Why fabric is so difficult to render digitally

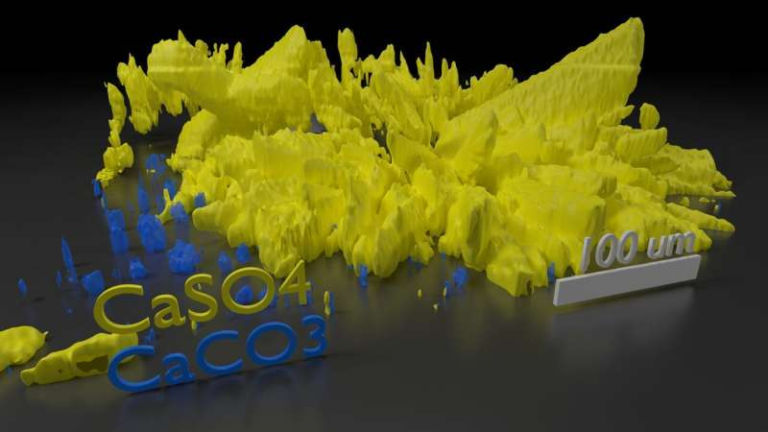

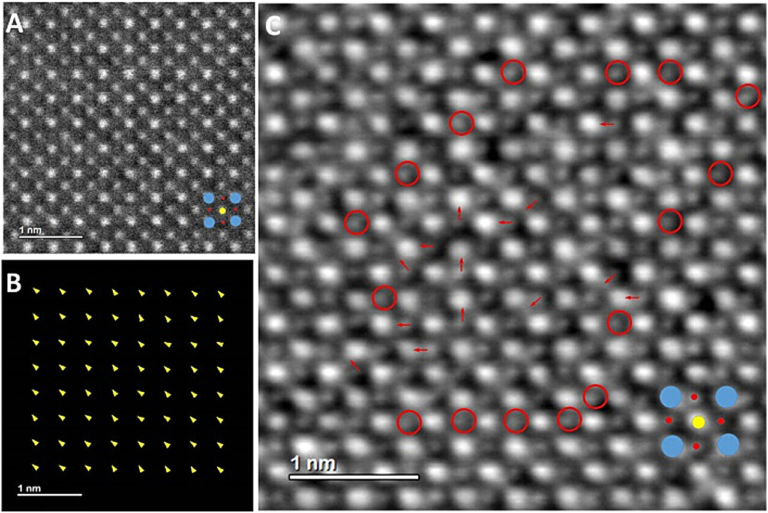

Unlike solid materials with continuous surfaces, fabric is essentially a loose assembly of fibers held together by friction. At the smallest scale, fibers twist together into plies, plies combine into yarn, and yarn is then woven or knitted into fabric. Each of these steps introduces variation, gaps, and irregularities that affect how light behaves.

The challenge becomes even greater when you consider that different fibers have different shapes. Wool fibers are roughly oval in cross-section, cotton fibers resemble kidney shapes, and silk fibers often form multi-sided polygonal shapes. All of this means light doesn’t just bounce off fabric—it passes through, bends, diffracts, and scatters in ways that are extremely hard to model accurately.

For decades, this complexity has frustrated artists and engineers alike. In film and animation, fabric often looks “off” in subtle but noticeable ways. Even when everything else in a scene feels real, cloth can break the illusion.

A long road of research and experimentation

Marschner began researching fabric rendering shortly after joining Cornell in 2002. Early efforts focused on simplified models that approximated how light reflects differently across a cloth surface. His first doctoral student in this area developed a model that captured some directional reflection effects, which was an important step but still far from fully realistic.

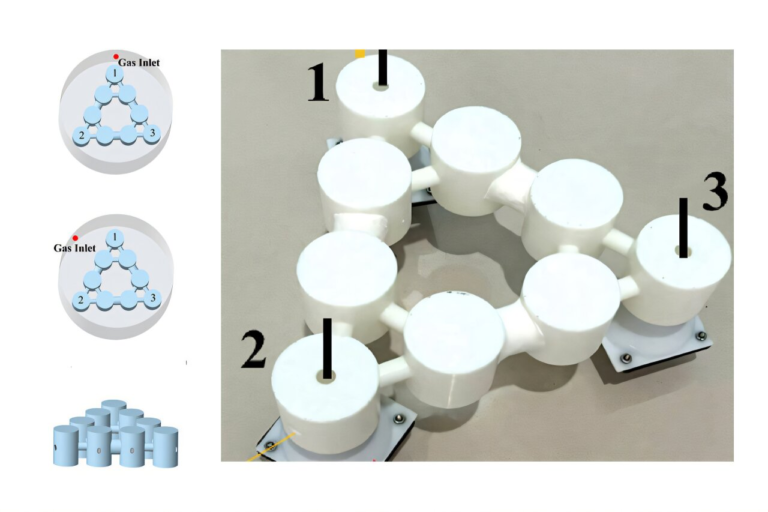

Over time, the research shifted toward understanding the underlying fiber structure of fabric. Marschner and collaborators, including Shuang Zhao and Kavita Bala, used microCT scanning to image fabrics at the scale of individual fibers. This allowed for highly accurate digital representations, but scanning every fabric was expensive, slow, and impractical for widespread use.

The team eventually refined these methods so that fabrics could be rendered without scanning each one individually. Some of this work even spun off into practical tools for interior designers, allowing them to visualize custom textiles before manufacturing.

Parallel to this, Marschner’s lab collaborated with Doug James, now at Stanford University, on physically simulating how yarns and fibers are arranged in woven and knitted materials. This research helped predict how a knitted pattern would look once executed with real yarn, bridging the gap between digital design and physical production.

The new breakthrough: combining rays and waves

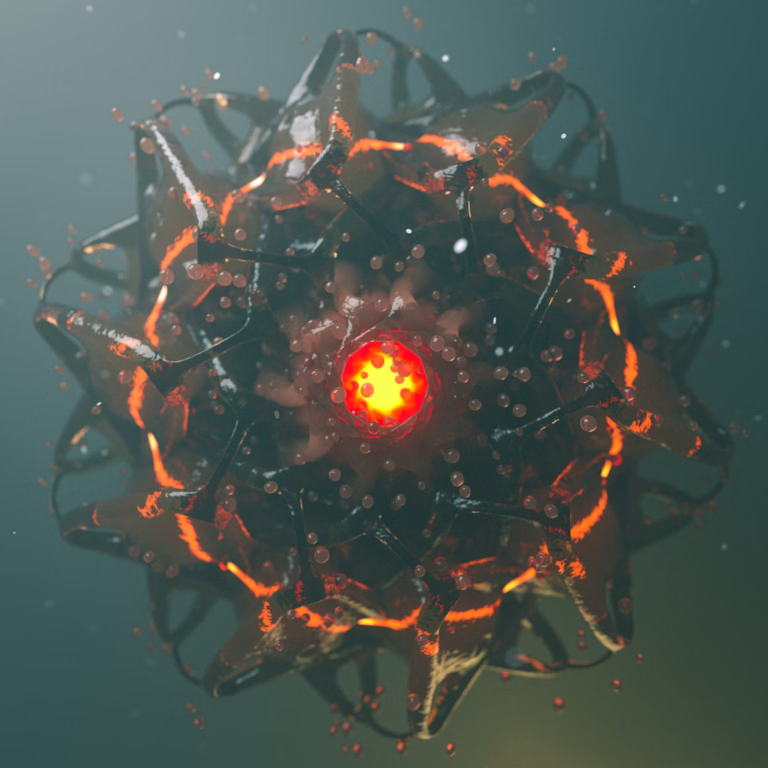

The latest advance builds on all of this prior work but introduces something entirely new. Yunchen Yu, a doctoral student at Cornell and the first author of the study, developed a model that treats light in two different ways at once: as rays and as waves.

Traditional rendering techniques mostly rely on ray optics, where light is simulated as straight lines that bounce off surfaces. Ray-based methods are relatively fast and work well for many materials, but they struggle to capture effects like diffraction, interference, and subtle sparkle, which are crucial for realistic fabric.

Wave optics, on the other hand, models light as a wave. This approach can capture those delicate effects, but it is extremely computationally expensive. Simulating everything using wave optics alone quickly becomes impractical, especially for real-time applications.

The new method solves this by using a hybrid ray-wave approach. Ray optics handle the bulk of the rendering, including the overall color of the fabric and the main highlights. Wave optics are used selectively to model light passing through gaps between fibers, light shining through fabric from behind, and the tiny glints and imperfections that make cloth feel real.

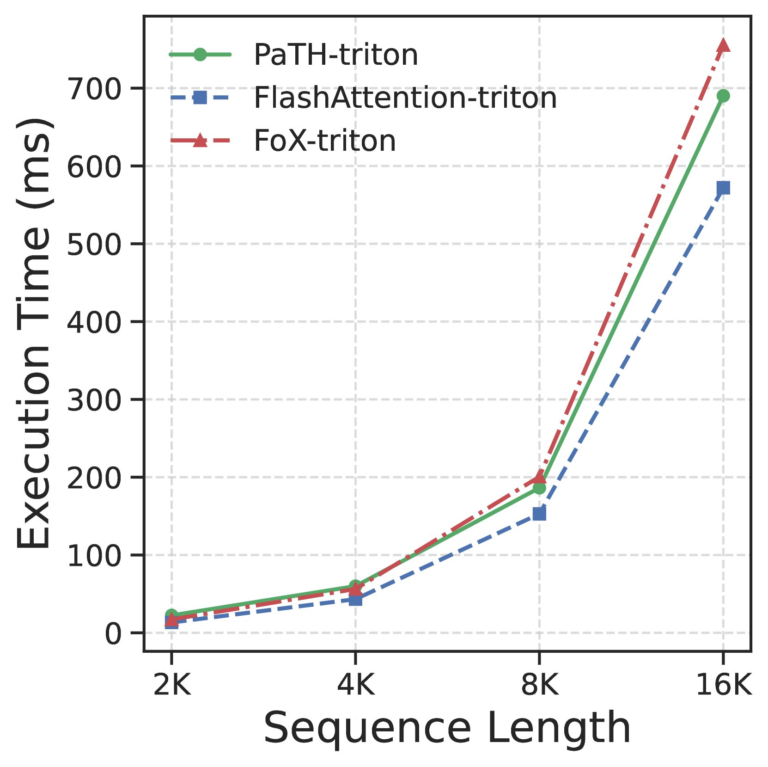

This approach is about 1,000 times faster than relying on wave optics alone, while still delivering a level of realism that wasn’t previously possible.

First fabric model to include wave optics

This research marks the first time wave optics have been integrated into a general fabric rendering model. The work builds on Yu’s earlier research on rendering iridescent feathers, where wave-based light behavior also plays a critical role.

Initially, Yu attempted to model fabric entirely using wave optics, but the computational cost was simply too high. The breakthrough came when she realized that ray optics could accurately capture the average appearance, while wave optics could be reserved for the fine details that truly matter.

The result is a system that captures translucency, shimmer, sparkle, and subtle light variation in a way that previous models could not.

What this means for games, films, and beyond

The implications of this work are wide-ranging. More realistic fabric rendering can significantly improve the visual quality of animated films, visual effects, and video games. It also has potential applications in virtual fashion, digital try-ons, interior design, and virtual reality.

Marschner expects that the next major leap will come from incorporating generative AI techniques. Instead of simulating every new fabric from scratch, AI models could learn from previous simulations and predict realistic appearances much faster. This would make high-quality cloth rendering accessible even for lower-budget projects and real-time applications.

Extra context: how cloth rendering fits into computer graphics

Fabric rendering sits at the intersection of physics, optics, and geometry. It draws on decades of research in shading models, material appearance, and light transport. What makes cloth unique is that it behaves neither like a smooth surface nor like a fully volumetric material—it exists somewhere in between.

As graphics hardware continues to improve and hybrid techniques like this one become more common, we’re likely to see a future where digital fabrics are indistinguishable from real ones, even under challenging lighting conditions.

For anyone who has ever noticed that digital clothing “just doesn’t look right,” this research represents a major step forward. It shows that realism doesn’t come from shortcuts alone, but from carefully understanding how the real world works and translating that knowledge into efficient computational models.

Research reference

Realistic Cloth Rendering with a Ray-Wave Hybrid Shading Model

https://doi.org/10.1145/3763359