What a Virtual Zebrafish Can Teach Us About Building Truly Autonomous AI

Artificial intelligence has made impressive progress over the past decade, but most AI systems still rely heavily on clear instructions, predefined goals, and external rewards. A robot vacuum, for example, may look smart, but it mainly follows maps and rules rather than genuinely exploring its environment. A recent research project from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) takes a very different approach, asking a simple but powerful question: What if AI learned to explore the world the way animals do?

Inspired by animal curiosity and biological intelligence, CMU researchers have created a virtual zebrafish that behaves like a real animal—without being trained on real animal data and without being told what to do. The project offers new insights into autonomous AI, intrinsic motivation, and curiosity-driven learning, and it may point the way toward future AI systems that can explore complex problems on their own.

Why Animal Curiosity Matters for AI

Animals with extremely small brains often display remarkable autonomy. They explore unfamiliar environments, adapt to failure, and try again after setbacks. This contrast is especially striking when compared to many modern AI systems that require extensive training data and carefully engineered reward functions.

The CMU team focused on animal curiosity as a core design principle. Instead of teaching an AI agent how to behave step by step, they aimed to create an agent that could discover useful behaviors on its own, simply by interacting with its environment and learning from the results.

This approach is especially relevant for the idea of AI agent scientists—autonomous systems that could analyze massive scientific datasets, explore hypotheses, and uncover patterns without human bias or constant supervision.

Why Zebrafish Were the Ideal Model

The researchers chose larval zebrafish for very specific reasons. Zebrafish are a well-established model organism in neuroscience, and scientists already have detailed data on their brain activity, behavior, and cellular structure.

One particularly important area of prior research involves glial cells, which were once thought to play only a supporting role in the brain. Studies in zebrafish have shown that glial cells actively influence behavior, especially during exploration and recovery from failure.

This made zebrafish a perfect candidate for studying how simple biological systems generate flexible, goal-free exploration, and how those mechanisms might be translated into artificial agents.

The Creation of a Virtual Zebrafish

Using insights from biology and neuroscience, the CMU team built a simulated larval zebrafish inside a virtual environment. Crucially, this AI agent was not trained using videos of real zebrafish, imitation learning, or reinforcement learning rewards.

Instead, the virtual zebrafish was allowed to freely explore its environment using a newly developed intrinsic motivation framework. The researchers then evaluated whether its behavior and internal dynamics resembled those of real animals.

The results were striking. The virtual zebrafish exhibited animal-like exploration patterns, internal brain-like activity, and even behavioral states that were not explicitly programmed into the system.

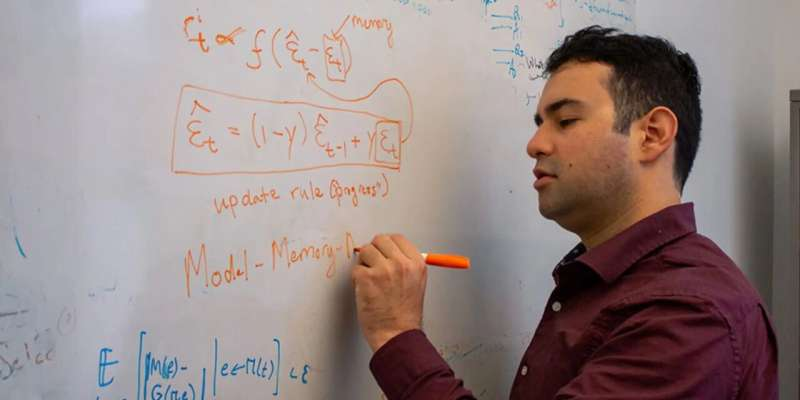

Understanding the 3M-Progress Model

At the heart of the project is a computational framework called Model-Memory-Mismatch Progress, often shortened to 3M-Progress. This model allows an AI agent to explore and adapt without relying on rewards, labels, or predefined objectives.

The system works through three tightly connected components:

- Model: The agent builds an internal understanding of how its world works based on sensory input.

- Memory: This includes both short-term memory of recent experiences and ethologically relevant prior memory, meaning basic expectations about how actions should affect the environment.

- Mismatch: When what the agent experiences does not match its expectations, this mismatch signals that something new or important is happening.

Rather than chasing novelty for its own sake, the agent tracks progress in resolving these mismatches. This creates a form of meaningful curiosity, pushing the agent toward exploration that improves its understanding of the world instead of random behavior.

Simulating Failure and Futility-Induced Passivity

One of the most fascinating parts of the study involved recreating a known biological phenomenon called futility-induced passivity. In real zebrafish, when their ability to swim is temporarily blocked, they initially struggle, then stop moving for a while, and eventually try again.

This behavior is linked to interactions between neurons and glial cells in the brain. The researchers wanted to see whether the virtual zebrafish—without being taught this behavior—would show something similar.

It did.

When placed in a simulated situation where movement became ineffective, the virtual zebrafish reduced its activity, entered a passive state, and later resumed exploration. This cycle emerged naturally from the 3M-Progress objective, demonstrating that the model captures deep behavioral principles rather than surface-level imitation.

How This Differs from Traditional AI Curiosity

Many existing curiosity-driven AI systems rely on prediction error, rewarding agents for encountering surprising sensory inputs. While effective in some settings, these systems can become distracted by noise or meaningless novelty.

The 3M-Progress approach is different. It focuses on learning progress, not raw surprise. This means the agent is motivated to explore areas where it can improve its understanding, rather than endlessly chasing unpredictable stimuli.

This distinction is critical for building AI systems that operate in open-ended, real-world environments, where not all novelty is useful.

Predicting Whole-Brain Activity

Another major contribution of the research is its connection to neuroscience. The internal dynamics of the virtual zebrafish were able to predict whole-brain activity at single-cell resolution, aligning closely with observed data from real zebrafish brains.

This suggests that the model does more than generate realistic behavior—it may also capture how biological brains organize exploration and decision-making. For researchers, this creates a valuable bridge between artificial intelligence and systems neuroscience.

What This Means for the Future of AI

The implications of this work go well beyond zebrafish. By demonstrating that intrinsic motivation and biological priors can produce autonomous, flexible behavior, the research opens new pathways for AI development.

Potential applications include:

- Autonomous scientific discovery, where AI agents explore data without human-imposed hypotheses

- Robotics, especially in unpredictable environments where reward functions are hard to define

- Cognitive modeling, helping scientists understand how intelligence emerges from simple components

The researchers emphasize that this is just the beginning. As AI systems tackle more complex problems, solutions may increasingly resemble biological intelligence, not because of imitation, but because there are only so many effective ways to solve open-ended exploration.

A Quick Look at Zebrafish in Research

Beyond AI, zebrafish are widely used in studies of learning, memory, development, and neurological disorders. Their transparent larvae allow scientists to observe brain activity in real time, making them uniquely valuable for connecting behavior to neural processes.

This project adds another reason zebrafish matter: they offer a powerful blueprint for understanding autonomy itself.

Research Reference

Intrinsic Goals for Autonomous Agents: Model-Based Exploration in Virtual Zebrafish Predicts Ethological Behavior and Whole-Brain Dynamics

https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.00138