MorphoChrome Pairs Software With a Handheld Device to Make Everyday Objects Iridescent

Gemstones like precious opals have fascinated humans for centuries because they seem to change color as you move them, never settling on a single shade. This shimmering effect is not caused by pigments, but by something far more intricate known as structural color. Instead of absorbing and reflecting specific wavelengths like dyes or paints, structural color emerges from microscopic physical structures that bend and scatter light in precise ways. It is the same phenomenon responsible for the glowing wings of butterflies, the radiant tails of peacocks, and the metallic sheen seen in certain beetles.

For years, scientists and designers have tried to harness structural color outside of tightly controlled laboratory settings. While progress has been made, the process has largely remained complex, expensive, and inaccessible for everyday creators. That is exactly the challenge a team of researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) set out to tackle. Their new system, called MorphoChrome, introduces a practical way to design, program, and apply iridescent structural color directly onto common objects.

At its core, MorphoChrome is a combination of software and a handheld optical fabrication device that allows users to “paint with light.” Instead of mixing pigments on a palette, users select colors digitally and project them as precisely controlled laser light onto a special holographic film. The result is a customizable, color-shifting surface that can be transferred onto 3D-printed items, flexible materials, fashion accessories, and more.

How MorphoChrome Actually Works

The MorphoChrome workflow is surprisingly straightforward. Users begin by connecting the handheld device to a computer using a USB-C cable. A dedicated software interface lets them select colors from a digital color wheel. Once a color is chosen, the system sends instructions directly to the handheld tool, which converts digital color data into real-world laser light.

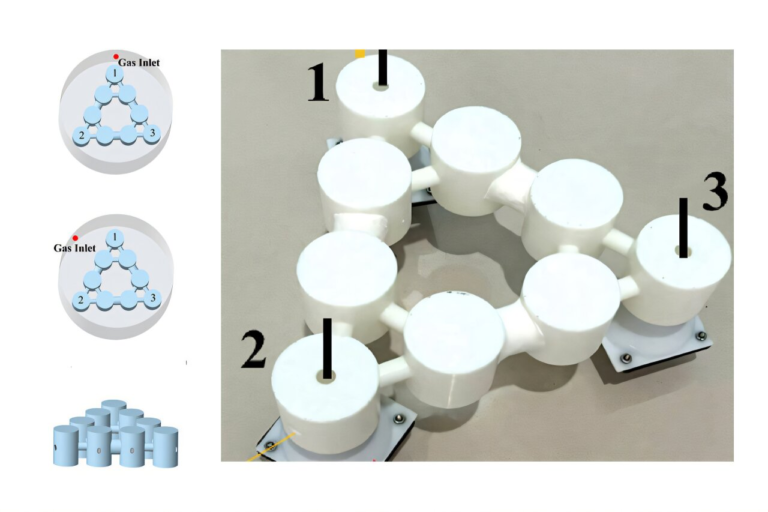

Inside the device, three lasers—red, green, and blue—are housed within a compact optical system roughly the size of a glue bottle. These lasers are activated at different intensities depending on the selected color. Mirrors guide the beams toward an optical prism, where they mix into a single, precisely tuned beam of light. This beam is then projected onto a holographic photopolymer film, the same type of material commonly used in passports, ID cards, and credit card security features.

As the laser light exposes the film, it alters the microscopic structure of the photopolymer layer. These structural changes determine how light will later reflect off the surface, creating vivid, angle-dependent color effects. In other words, the color isn’t printed on the surface—it’s embedded into the structure itself.

Exposure time plays an important role in the process. Each laser wavelength requires a different amount of time to fully saturate the film. Green light activates fastest at about 2.5 seconds, red takes around 3 seconds, and blue requires roughly 6 seconds. This difference comes from the intrinsic energy requirements of each wavelength, with blue light needing more exposure to achieve the same structural effect.

Transferring Iridescence Onto Objects

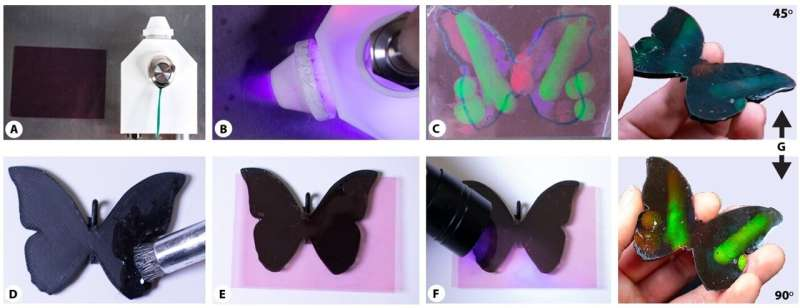

Once the holographic film has been “painted” with light, the next step is transferring that structural color onto an object. The researchers developed a UV-curable epoxy resin process to make this possible. First, a thin layer of epoxy resin is applied to the target object, which could be a rigid 3D-printed form or a flexible surface like fabric or leather.

The exposed holographic film—made of a photopolymer layer backed by protective plastic—is then pressed onto the resin-coated object. A handheld ultraviolet light cures the epoxy in about 20 seconds, bonding the film to the surface. After curing, the protective plastic layer is peeled away, leaving behind a jewel-like, structurally colored polymer that appears embedded in the object itself.

The final result is striking. Colors shift dramatically depending on viewing angle, much like natural iridescent materials. In one demonstration, a butterfly design appeared bright green when viewed head-on and transitioned to deep blue when seen from a 45-degree angle, echoing the appearance of real Papilio and Blue Morpho butterflies.

Practical Demonstrations and Real-World Uses

To show the versatility of MorphoChrome, the team applied it to a variety of objects. A plain black butterfly necklace charm was transformed into a radiant pendant with shimmering green, blue, and orange highlights. Golf gloves were turned into training tools that glow green only when held at the correct angle, offering immediate visual feedback to beginners. Even fingernails were adorned with gemstone-like finishes, demonstrating the system’s potential for cosmetics and fashion.

What makes MorphoChrome especially notable is that it allows for on-demand customization. Designers are no longer limited to pre-made iridescent materials like feathers or gems. Instead, they can program structural color patterns in real time, directly tailored to their design needs.

Building on Earlier Research

MorphoChrome builds on previous work in stretchable structural color developed by researchers at MIT’s Laboratory for Biologically Inspired Photonic Engineering, including earlier contributions from Benjamin Miller and Professor Mathias Kolle. The current project also fits within CSAIL’s broader research agenda focused on merging computation with novel materials to create interactive and programmable physical interfaces.

The team behind MorphoChrome includes Paris Myers, Yunyi Zhu, and Benjamin Miller, with Stefanie Mueller serving as the senior author and principal investigator. Their work was presented as a demo paper and poster at the 2025 ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication, highlighting its emphasis on accessibility and hands-on fabrication.

Why Structural Color Matters Beyond Aesthetics

Structural color offers advantages that go beyond visual appeal. Because it relies on physical microstructures rather than chemical pigments, it tends to be more durable and fade-resistant over time. It also opens doors to functional applications, such as encoding information that is only visible from certain angles or under specific lighting conditions.

The MorphoChrome team is already exploring future possibilities, including full light-field holographic designs embedded into a single film. This could enable objects like passports or ID cards to display three-dimensional verification symbols when viewed correctly. Another potential direction involves adaptive camouflage, inspired by animals that use structural color to blend into their environments. Soft robots, for example, could change their appearance in real time to match surrounding terrain.

There are still areas to improve. The researchers want to expand the system’s color gamut, increase brightness for mixed colors, and refine the device’s casing, as the current 3D-printed housing allows some light leakage. Even so, MorphoChrome already represents a major step toward making structural color accessible outside specialized labs.

A New Tool for Creative and Technical Exploration

By simplifying a traditionally complex process, MorphoChrome gives artists, designers, engineers, and hobbyists a new way to explore color as a programmable material. It bridges the gap between natural optical phenomena and everyday fabrication, turning iridescence into something that can be designed, controlled, and applied almost as easily as paint.

As interest grows in smart materials and interactive surfaces, tools like MorphoChrome hint at a future where color itself becomes a dynamic interface—one shaped not by pigments, but by light and structure working together.

Research paper: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3654777.3689505