Emerging Solar Cell Material Sets a New Efficiency Record and Signals a Promising Future for Solar Technology

Engineers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have achieved a significant milestone in solar energy research by setting a new world record efficiency for an emerging type of solar cell material known as antimony chalcogenide. This breakthrough could play an important role in making future solar panels cheaper, more efficient, and more durable, while also expanding the range of environments where solar technology can be used.

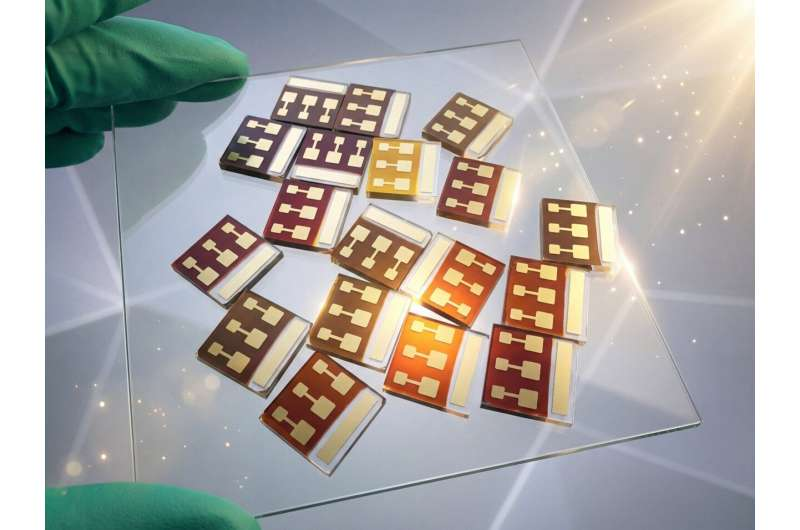

The research focuses on antimony chalcogenide solar cells, a class of photovoltaic devices that has been gaining attention as a strong candidate for next-generation solar technologies. In their latest work, the UNSW team achieved a certified power conversion efficiency of 10.7%, which is the highest independently verified efficiency for this material anywhere in the world so far.

This result was strong enough to earn antimony chalcogenide its first-ever inclusion in the international Solar Cell Efficiency Tables, a globally recognized benchmark that tracks record-setting solar cell performances across different materials. Reaching this table is a major indicator that a material is no longer just experimental curiosity but a serious contender in the solar research landscape.

Beyond the record itself, the researchers also identified the fundamental chemical mechanism that had been holding the material back for years. This insight explains why previous attempts failed to push efficiency past a stubborn ceiling and opens the door to faster and more reliable improvements in the future.

What Makes Antimony Chalcogenide So Interesting?

Antimony chalcogenide, chemically written as Sb₂(S,Se)₃, stands out for several practical reasons that make it attractive for real-world solar applications.

First, it is made from abundant and relatively low-cost elements, especially when compared to some high-performance solar materials that rely on scarce or expensive components. This matters because material cost plays a major role in determining whether a new solar technology can scale beyond the laboratory.

Second, antimony chalcogenide is inorganic, which gives it a natural advantage in terms of long-term stability. Many newer solar materials show impressive efficiencies but degrade over time. Inorganic compounds like this one are generally more resistant to heat, moisture, and environmental stress.

Third, the material has a very high light absorption coefficient. In practical terms, this means a layer just 300 nanometers thick—about one-thousandth the thickness of a human hair—is enough to absorb sunlight efficiently. Thin absorber layers reduce material usage and enable flexible or semi-transparent designs.

Another key advantage is that the material can be deposited at low temperatures, which lowers energy consumption during manufacturing. This also makes it compatible with a wider range of substrates and supports large-scale, low-cost production methods.

The Efficiency Barrier That Held the Material Back

Despite all these advantages, antimony chalcogenide solar cells faced a frustrating problem. Since 2020, efficiency improvements had stalled at around 10%, and progress seemed stuck.

The UNSW team discovered that the core issue was related to how sulfur and selenium—the two chalcogen elements in the material—were distributed during the manufacturing process. Instead of forming a uniform structure, these elements tended to separate unevenly.

This uneven distribution created what researchers describe as an energy barrier inside the solar cell. The barrier made it harder for electrical charges generated by sunlight to move through the absorber layer. As a result, many charges were lost before they could be collected, limiting the overall efficiency of the device.

In simple terms, the material structure was working against itself, even though the basic chemistry was sound.

The Key Fix That Changed Everything

The breakthrough came when the researchers introduced a small amount of sodium sulfide during the hydrothermal deposition process, which is used to form the solar-absorbing layer.

This small chemical addition played a big role. Sodium sulfide helped stabilize the reaction kinetics, allowing sulfur and selenium to distribute more evenly throughout the material. With the internal composition properly balanced, the energy barrier was reduced, and electrical charges could move more freely.

In UNSW’s laboratory tests, the improved solar cells reached a power conversion efficiency of 11.02%. This result was then independently certified at 10.7% by CSIRO, one of nine internationally recognized photovoltaic measurement centers worldwide.

The researchers note that while this is a major step forward, there is still room for improvement. Reducing defects in the material remains a key goal, and this will be addressed through chemical passivation techniques in future studies.

Why This Matters for Tandem Solar Cells

One of the most exciting implications of this work lies in tandem solar technology. Tandem cells stack two or more solar cells on top of each other, with each layer absorbing different parts of the sunlight spectrum.

Traditional silicon solar cells are already highly optimized, but they cannot capture all available solar energy efficiently on their own. A suitable top cell material is needed to push overall efficiency higher.

Antimony chalcogenide is emerging as a promising top-cell candidate. Its bandgap, stability, and thin-film nature make it compatible with silicon, and researchers see it as one of several materials that could help define the future of tandem solar panels.

Applications Beyond Rooftop Solar Panels

The potential uses of antimony chalcogenide extend well beyond standard solar modules.

The material’s ultrathin structure, semi-transparency, and high bifaciality of 0.86 make it suitable for see-through solar windows. These could allow buildings to generate electricity without sacrificing natural light.

A UNSW spinout company called Sydney Solar is already working on scaling up solar “stickers” for windows, pointing toward practical commercialization pathways.

Another interesting application lies in indoor solar energy harvesting. The material’s bandgap matches well with indoor lighting spectra, making it effective under low-light conditions. This opens up possibilities for powering smart badges, e-paper displays, self-powered sensors, and internet-connected devices, where stability and safety matter more than maximum efficiency.

Looking Ahead

The UNSW team believes that with further refinement—especially through defect passivation—efficiencies of around 12% are achievable in the near future. More importantly, the understanding gained from this study provides a clear roadmap for continued improvement.

By solving a long-standing chemical problem and demonstrating certified, record-setting performance, antimony chalcogenide has moved from a promising idea to a serious contender in next-generation solar technology.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-025-01952-0