Do-It-Yourself Ammonia Production Uses Renewable Power and Calcium to Cut Emissions for Farmers

Ammonia is one of those chemicals most people don’t think about until they’re scrubbing a stubborn stain off a window or cleaning a kitchen appliance. Yet beyond household cleaners, ammonia plays a massive role in modern life. It is the backbone of global fertilizer production, supporting crops like corn, cotton, and soybeans, and by extension, feeding billions of people worldwide. Every year, more than 170 million metric tons of ammonia are produced globally, making it one of the most important industrial chemicals on Earth.

Now, researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) are working on a radically different way to make ammonia—one that could allow farmers to produce it locally, using renewable electricity and abundant natural materials, rather than relying on massive industrial plants. Their work, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, explores a cleaner, lower-emissions method that could reshape how fertilizer is made and distributed in the future.

Why Ammonia Matters So Much

Ammonia is chemically simple, made up of nitrogen and hydrogen, but its impact is enormous. Roughly 80% of global ammonia production ends up as fertilizer, enabling higher crop yields and faster food production. Without it, modern agriculture as we know it would struggle to function at scale.

However, the way ammonia is traditionally produced comes with a serious environmental cost. The industrial process used today is powerful and reliable, but also energy-hungry and carbon-intensive.

The Problem With Traditional Ammonia Production

For more than a century, ammonia has been made using the Haber-Bosch process, a method that forces nitrogen from the air to react with hydrogen under extremely high temperatures and high pressures. While effective, this process consumes vast amounts of energy and depends heavily on fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, which is used to produce hydrogen.

As a result, ammonia production is responsible for an estimated 1–3% of global carbon dioxide emissions. That might sound small, but on a planetary scale, it represents a significant contribution to climate change. The centralized nature of Haber-Bosch plants also means ammonia must be transported long distances, adding more emissions and costs along the supply chain.

These drawbacks have motivated scientists around the world to search for cleaner, more flexible alternatives.

A New Approach Using Calcium

The UIC research team, led by chemical engineering professor Meenesh Singh, set out to rethink ammonia production from the ground up. Their goal was to reduce emissions while also making production more accessible and scalable for smaller users, such as individual farmers or rural communities.

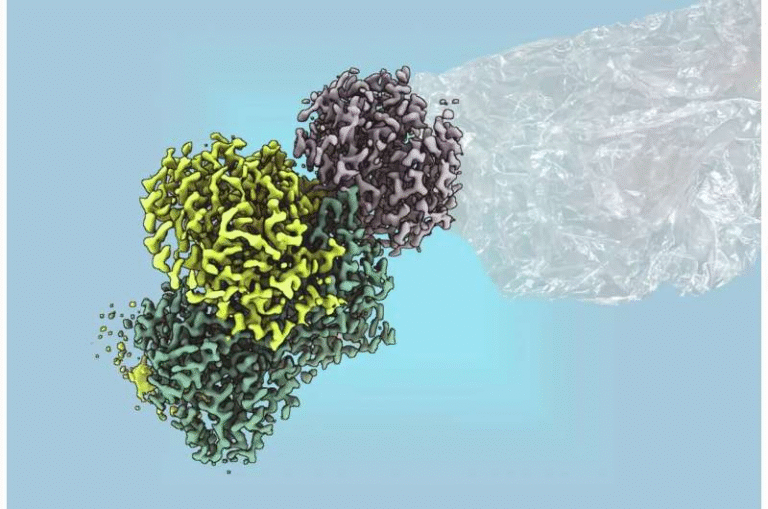

Instead of relying on intense heat and pressure, the team developed a process that uses calcium, an abundant and inexpensive mineral, to help convert nitrogen into ammonia. Calcium reacts with nitrogen to form calcium nitride, which can then combine with hydrogen to produce ammonia—all at room temperature.

This approach avoids carbon dioxide emissions entirely during the ammonia synthesis step. It also relies on renewable electricity, meaning the system could be powered by solar or wind energy.

Earlier experiments in this research area used lithium as a key material, but lithium’s limited availability and cost made large-scale deployment unrealistic. Calcium, by contrast, is widely available and far more practical for scaling up.

How the System Actually Works

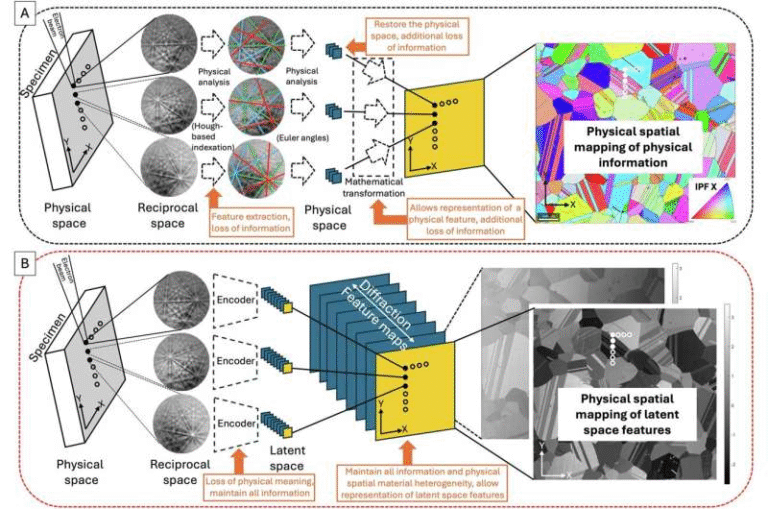

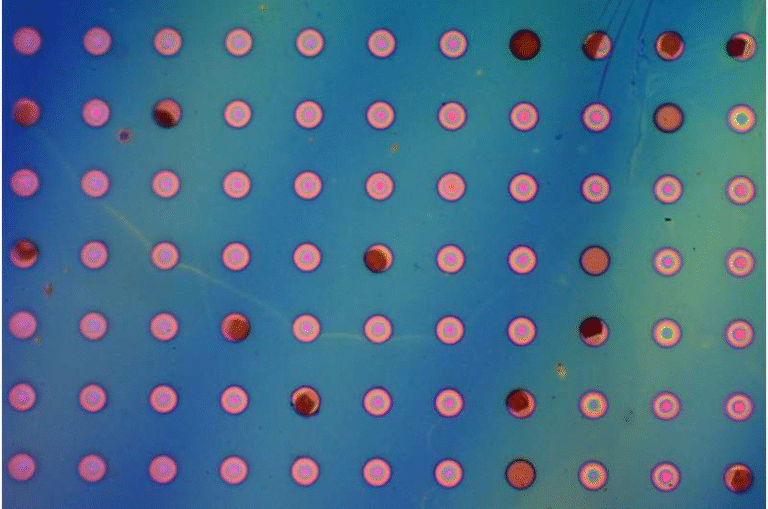

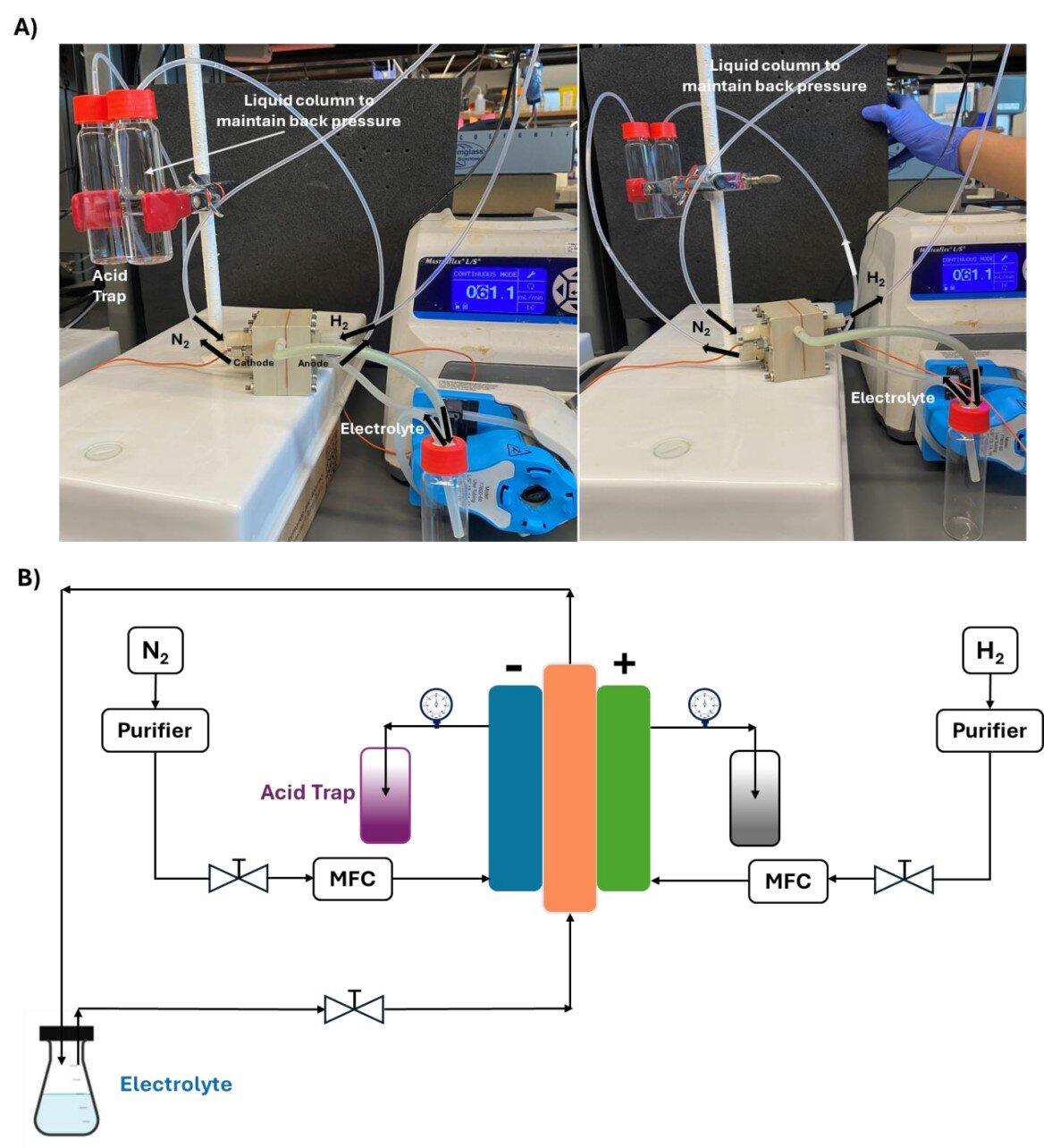

Physically, the current system is a continuous-flow electrochemical reactor roughly 1 square centimeter in size. Inside the reactor, nitrogen and hydrogen gases interact with calcium-based materials in a carefully controlled environment. A small pressure difference between the gas inlet and outlet is maintained using a water column, helping regulate the flow and stability of the reaction.

In its current form, the reactor produces about 1 gram of ammonia per day, roughly the weight of a jellybean. While modest, this output is significant for a proof-of-concept device and represents the most scaled-up version of this technology so far.

Importantly, the reaction takes place at ambient conditions, without the extreme pressures or temperatures required by traditional methods. Ethanol is used to help maintain ammonia production when nitrogen and hydrogen are supplied steadily.

Scaling From the Lab to the Field

Although the current reactor is small, the researchers have clear plans for scaling up. The next steps involve increasing the reactor size from 1 square centimeter to 100 square centimeters, and eventually to a full square meter.

UIC is collaborating with General Ammonia Co. to pilot and scale up the technology in the Chicago area. Their near-term goal is to produce 11 pounds of ammonia per day, a substantial jump from the lab-scale output and a meaningful step toward real-world applications.

The long-term vision is distributed ammonia production—small, modular systems that could be installed close to where fertilizer is actually needed. This could reduce dependence on centralized factories, lower transportation emissions, and give farmers more control over their fertilizer supply.

Why Distributed Ammonia Production Is Appealing

Local ammonia production offers several potential advantages. Farmers could produce fertilizer on demand, reducing costs and supply chain vulnerabilities. Rural or remote communities could gain more reliable access to essential agricultural inputs. And because the system can run on renewable electricity, it aligns well with broader efforts to decarbonize agriculture and industry.

From a global perspective, even partial adoption of low-emission ammonia technologies could significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions tied to food production.

Challenges That Still Remain

Despite its promise, the technology is not ready for widespread commercial use yet. Production rates are still relatively low, and further engineering work is needed to improve efficiency, durability, and cost-effectiveness.

Another key challenge is hydrogen supply. At present, the system relies on hydrogen gas. The team’s longer-term ambition is to start directly from water, generating hydrogen on-site and simplifying the overall setup even further.

Every step forward, however, represents progress toward a more flexible and sustainable ammonia economy.

The Broader Context of Green Ammonia

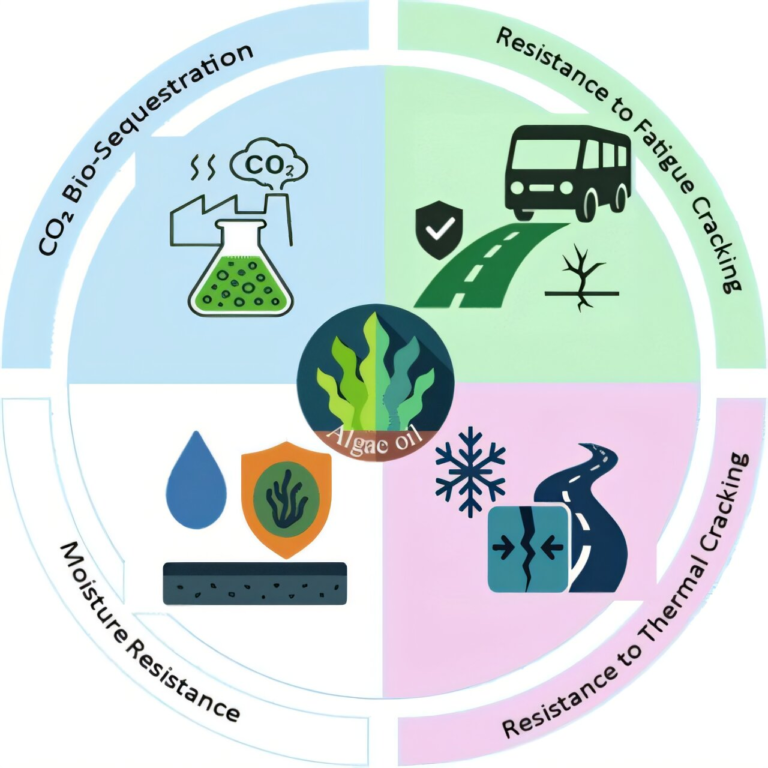

This calcium-mediated system is part of a wider global push toward green ammonia, which refers to ammonia produced with little or no carbon emissions. Researchers are exploring multiple pathways, including electrochemical, plasma-based, and renewable-powered approaches.

Ammonia itself is also gaining attention beyond agriculture, as a potential carbon-free energy carrier for shipping and power generation. Cleaner ways to produce it could therefore have impacts far beyond fertilizer.

Collaboration, Credit, and Next Steps

The study includes contributions from Ishita Goyal, Hasiya Najmin Isa, Vamsi Vikram Gande, and Rohit Chauhan, alongside Singh. UIC’s Office of Technology Management has filed a patent covering the calcium-mediated ammonia synthesis process, highlighting its potential commercial value.

For Singh and his team, the motivation is clear: improving food security while reducing environmental harm. With global demand for fertilizer continuing to rise, finding cleaner ways to make ammonia is becoming increasingly urgent.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2513960122