Engineers Create a Water-Saving Sand Layer to Help Plants Survive Drought Conditions

Drought has shaped human history for centuries, and it continues to challenge modern agriculture in serious ways. One striking historical example comes from the Anasazi people of the American Southwest, who once relied on crops like corn, squash, and beans to sustain their communities. Around 1276 A.D., a prolonged and severe drought made farming impossible, forcing them to abandon their settlements. While that story belongs to the past, drought itself is very much a present-day problem—and one that is expected to worsen as climate patterns continue to shift.

Against this backdrop, engineers at Texas A&M University have developed a promising new approach to help crops cope with water scarcity. Their solution is surprisingly simple in concept yet sophisticated in execution: a chemically modified sand layer that improves soil water retention and supports healthier plant growth during dry conditions.

Why Drought Is Becoming a Bigger Agricultural Threat

Droughts are no longer rare or isolated events. According to data from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, both the frequency and duration of droughts have increased by about 29% since 2000. Rising global temperatures intensify the problem by increasing evaporation rates, which dry out soils and reduce the availability of surface and groundwater.

Even with modern irrigation technologies, farmers often struggle to maintain consistent water supplies during extended dry periods. This is especially true in southern U.S. states like Texas, where summer temperatures regularly soar. In such environments, improving how soils retain water can make a major difference in agricultural productivity.

Rethinking Sand as a Tool for Water Management

The research team at Texas A&M approached this challenge from a materials science perspective. Instead of focusing solely on irrigation methods, they asked a different question: What if the soil itself could be engineered to hold water more effectively?

Sand is a fundamental component of many soils, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. However, sandy soils drain water very quickly, which means crops often require frequent irrigation. To address this, the researchers chemically modified ordinary sand to make it hydrophobic, or water-repellent.

At first glance, making sand repel water might sound counterintuitive. But the key lies in where and how the modified sand is used.

The Science Behind Hydrophobic Sand

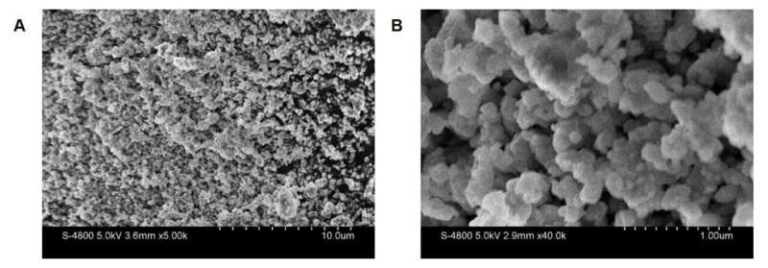

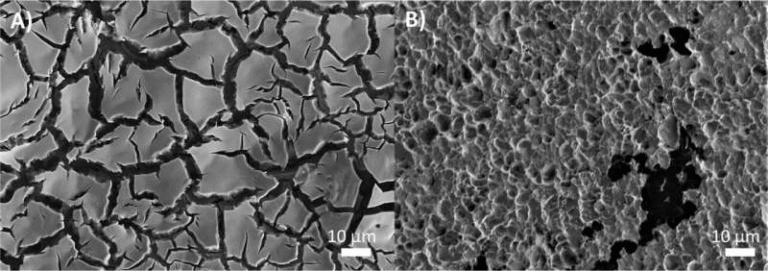

At the microscopic level, sand is largely made of silica, whose surface is covered with reactive hydroxyl groups. The researchers took advantage of this natural surface chemistry by binding these hydroxyl groups with organosilane compounds. This process alters the surface properties of the sand particles, making them hydrophobic.

Importantly, this modification is incredibly thin. The chemical layer applied to the sand surface is less than two nanometers thick, which is thousands of times thinner than a human hair. This means the sand’s physical structure remains unchanged, while its interaction with water is completely transformed.

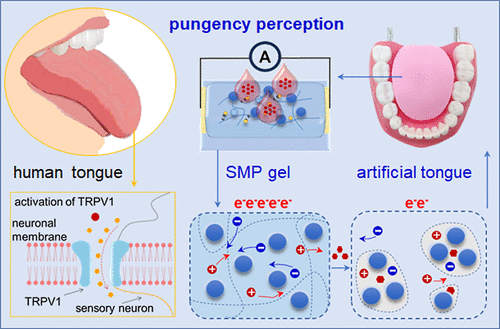

How the Sand Layer Works in Soil

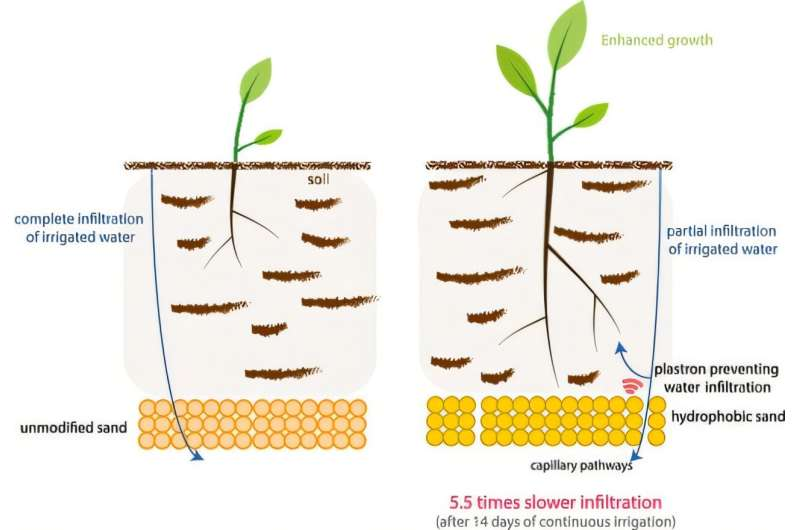

Rather than mixing the hydrophobic sand throughout the soil, the researchers propose placing it as a subsurface layer just below the plant root zone, roughly two to three inches thick. When water moves downward through the soil after irrigation, this hydrophobic layer slows the drainage process.

As a result, more water remains available in the root zone for a longer period, giving plants additional time to absorb moisture. The approach enhances water retention without significantly altering the chemistry of the soil where roots are actively growing.

Testing the Idea With Tomato Plants

To test their hypothesis, the team conducted controlled laboratory experiments designed to mimic real agricultural conditions. They used plastic cups layered with normal sand at the bottom and dry soil at the top. In some of the samples, a layer of hydrophobic sand was added at the bottom.

Tomato seeds were planted in each cup, and all samples were irrigated daily. The researchers carefully collected and measured the drained water to assess how much moisture was retained in each setup.

The results were clear. Samples containing the hydrophobic sand layer showed significantly less water drainage compared to the control samples. More importantly, this improved water retention translated directly into better plant performance.

Strong Growth Results Under Water Stress

The tomato seedlings grown above the hydrophobic sand layer demonstrated nearly twice the growth stature of those grown in unmodified soil. The researchers observed a direct positive relationship between enhanced water retention and plant growth, confirming that the sand layer was effectively supporting the crops.

This finding highlights the potential of the approach not just to conserve water, but also to improve crop resilience and productivity under drought conditions.

Minimal Disruption, Long-Term Stability

One of the most appealing aspects of this technology is its minimal invasiveness. The researchers envision using an injection-based system to place the modified sand layer below the roots without disturbing the topsoil. This targeted approach helps preserve the natural soil environment where plants interact most directly with nutrients and microbes.

The modified sand itself is chemically stable, meaning it does not break down easily or release harmful substances into the soil. This stability could make it suitable for long-term agricultural use, though further field studies are needed to confirm its durability and environmental impact.

Where This Technology Could Be Most Useful

The hydrophobic sand layer is especially promising for porous soils, such as sandy soils, that typically suffer from poor water and nutrient retention. These soils often require more frequent irrigation and fertilization, increasing costs for farmers and pressure on water resources.

By improving water-holding capacity at the subsurface level, this approach could help reduce irrigation demand while maintaining healthy crop growth—an important step toward more sustainable agriculture in water-limited regions.

How This Fits Into Broader Soil and Water Research

This work builds on a growing body of research exploring how soil structure and surface chemistry influence water movement. Previous studies have examined hydrophobic soil coatings and mulches to reduce evaporation at the surface. What sets this research apart is its focus on controlling water percolation below the root zone, rather than simply preventing surface water loss.

The study also contributes to ongoing discussions about climate adaptation in agriculture, offering a practical example of how materials science and chemical engineering can address environmental challenges.

Looking Ahead

While the laboratory results are encouraging, the researchers acknowledge that large-scale field testing will be essential. Questions remain about cost, scalability, long-term effects on soil ecosystems, and performance across different crop types and soil compositions.

Still, the idea of transforming something as common as sand into a tool for drought resilience underscores the power of rethinking everyday materials. As droughts become more frequent and intense, innovations like this could play a key role in helping agriculture adapt to a changing climate.

Research paper:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c03952