New Tool Narrows the Search for Ideal Metal Organic Frameworks

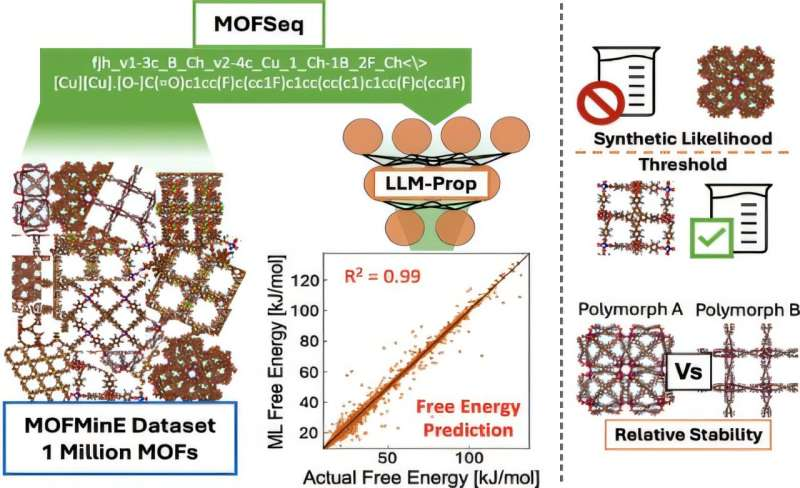

Researchers at Princeton University have developed a powerful machine-learning tool that could dramatically speed up how scientists discover and evaluate metal organic frameworks, commonly known as MOFs. These materials have been exciting chemists, engineers, and materials scientists for years because of their unusual structure and enormous potential across industries. What this new research does is tackle one of the biggest bottlenecks in MOF development: figuring out which of the countless possible structures are actually worth pursuing.

MOFs are a class of advanced materials made from metal-ion nodes connected by organic molecules, forming vast, highly ordered networks. On a microscopic level, they resemble tiny sponges filled with pores. This gives them an incredibly large internal surface area, which is why they are so promising for tasks like carbon capture, gas separation, energy storage, catalysis, battery chemistry, and even clean water purification.

The problem is scale. Because MOFs are modular, researchers can theoretically combine metals and organic linkers in trillions of different ways. While that sounds like a dream for innovation, it quickly becomes a nightmare when trying to determine which combinations are stable, useful, and realistically synthesizable in a laboratory. Traditional computational methods, such as molecular simulations, are accurate but painfully slow, often taking many hours or even days to evaluate a single structure.

The Princeton-led team, headed by computer scientist Adji Bousso Dieng, set out to change that.

Using Machine Learning to Cut Through the Noise

At the heart of this research is a machine-learning model designed to predict a key physical property known as free energy. In simple terms, free energy is a measure of how stable a material is. For MOFs, free energy is especially important because it correlates strongly with whether a structure can actually be made in the lab without falling apart.

Instead of relying on traditional simulations, the new tool predicts free energy values in seconds. That represents an enormous leap forward when compared to older approaches that could take anywhere from seven hours to more than two days for a single calculation.

The idea is straightforward but technically demanding: if you can rapidly estimate the free energy of a MOF, you can quickly rule out unstable or impractical candidates and focus experimental and computational resources on the most promising ones.

Turning MOFs Into a Language Machines Can Understand

One of the most challenging parts of the project was figuring out how to represent MOFs in a way that a machine-learning system could understand. MOFs are complex three-dimensional structures with detailed chemical and physical interactions, which do not naturally translate into simple numerical inputs.

To solve this, the team developed a sequence-based representation that converts the physical and chemical characteristics of a MOF into a format similar to a language sequence. This representation encodes information related to atomic interactions, structural units, and energetic contributions tied directly to free energy.

This step turned out to be the real breakthrough. Once the researchers had a reliable way to express MOFs as sequences, they could apply techniques similar to those used in language models, training the system to recognize patterns that correlate with stability.

Using this method, the team generated machine-readable representations for one million distinct MOF structures. That alone would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Training and Testing the Model

With this massive dataset in hand, the researchers trained a custom-built language model to predict free energy values. The model was calibrated using a simpler property that closely tracks free energy, making the training process more efficient.

To evaluate accuracy, the team tested the model against a subset of roughly 65,000 MOFs whose free energy values were already known from prior simulations. The results were striking: the predictions matched known values with 97% accuracy.

That level of precision is more than enough to confidently screen materials before committing to expensive simulations or laboratory synthesis.

Knowing Which MOFs Can Actually Be Made

An important part of this research builds on earlier work by Dieng’s collaborator, Diego Gómez-Gualdrón from the Colorado School of Mines. That earlier research identified a free energy threshold—about 4.4 kilojoules per mole—below which a MOF is considered stable enough to be feasibly synthesized.

By predicting free energy, the new tool does more than just estimate stability. It also allows researchers to make a clear yes-or-no judgment about whether a newly designed MOF is likely to be synthesizable. That kind of insight is invaluable when deciding where to invest time and funding.

Why This Matters for Real-World Applications

MOFs have long been described as “materials of the future,” but progress has been slowed by the difficulty of navigating their immense design space. This new approach helps lift that burden.

With rapid predictions, scientists can now explore MOFs for carbon capture systems that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, energy storage materials for next-generation batteries, gas separation membranes for industrial processes, and catalysts that speed up chemical reactions with greater efficiency.

Just as importantly, the tool helps researchers avoid wasting effort on structures that look interesting on paper but are fundamentally unstable.

What Comes Next

The team is not stopping here. They are currently working on streamlining the sequence representation, reducing the computational overhead required for especially large or complex MOFs. They are also developing a search function that would allow scientists to quickly identify stable MOFs with specific desired properties, rather than manually sifting through enormous databases.

The long-term vision is a system where researchers can define what they need—such as pore size, stability, or energy characteristics—and quickly find a shortlist of realistic candidates.

A Bigger Trend in Materials Science

This work fits into a growing movement toward AI-driven materials discovery. Similar machine-learning approaches are now being applied to batteries, semiconductors, polymers, and pharmaceuticals. Instead of replacing physical understanding, these models act as powerful filters, narrowing down options so human expertise can be applied where it matters most.

In the case of MOFs, the combination of chemical insight, physics-based thresholds, and machine learning offers a practical way forward in a field that was once overwhelmed by its own possibilities.

Understanding Metal Organic Frameworks a Bit More

For readers less familiar with MOFs, it’s worth emphasizing why they generate so much excitement. Their tunable structure allows scientists to precisely control pore size, chemical functionality, and reactivity. This makes them uniquely adaptable compared to traditional materials like activated carbon or zeolites.

However, that same flexibility is what makes MOFs so difficult to study at scale. Every new combination creates a new material with its own behaviors. Tools like this new Princeton model may finally allow researchers to explore that flexibility without getting lost in it.

By turning MOF discovery into a data-driven process guided by physical principles, this research marks a significant step toward making advanced materials discovery faster, smarter, and more efficient.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c13960