Identifying Where Lithium Ions Sit in a New Solid-State Electrolyte That Could Lead to Better Batteries

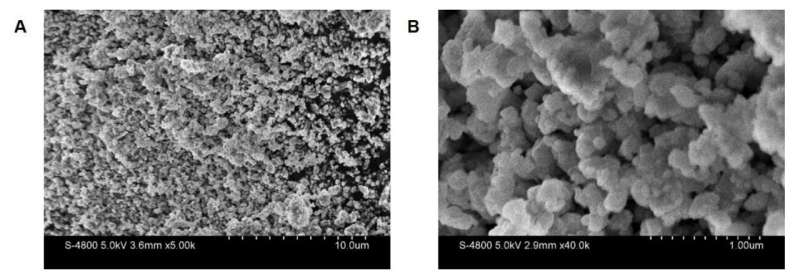

Recent research published in the journal Science has introduced a new solid-state electrolyte that could significantly improve the performance of next-generation lithium batteries, especially in cold-temperature conditions. The study focuses on a newly developed material called lithium tantalum oxychloride, commonly referred to as LTOC, and explains why it allows lithium ions to move unusually fast and efficiently through a solid structure.

Solid-state batteries are widely seen as the future of energy storage. They promise higher energy density, better safety, and longer lifespans than today’s lithium-ion batteries, which rely on flammable liquid electrolytes. However, one major obstacle has been finding solid electrolytes that allow lithium ions to move easily, particularly at lower temperatures. This is where LTOC stands out.

The research was conducted by an international team of scientists and included contributions from James Kaduk, a Research Professor of Chemistry at the Illinois Institute of Technology. His key role in the project was identifying where lithium ions are located within the crystal structure of this new material, a detail that turned out to be crucial for understanding why LTOC performs so well.

A New Kind of Solid Electrolyte

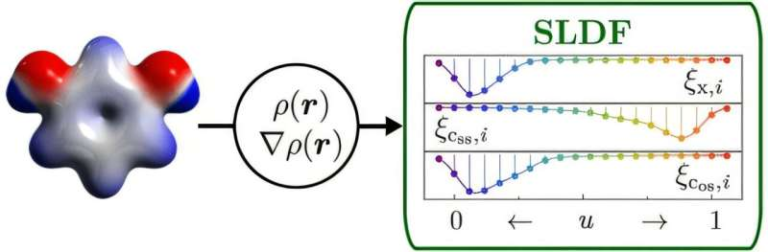

The full title of the research paper is “Anion Sublattice Design Enables Superionic Conductivity in Crystalline Oxyhalides.” At the center of the study is LTOC, a crystalline material made from lithium, tantalum, oxygen, and chlorine. What makes it special is the way these elements are arranged at the atomic level.

Unlike many traditional solid electrolytes, LTOC uses a mixed-anion design, meaning it contains more than one type of negatively charged ion. In this case, oxygen and chlorine form the anion framework. This mixed structure creates a rigid but open lattice that leaves clear pathways for lithium ions to move through.

Measurements showed that LTOC has exceptionally high ionic conductivity, reaching values comparable to or even exceeding some liquid electrolytes. Even more impressive is its low activation energy, which means lithium ions can move with minimal resistance. This high conductivity remains stable even at sub-zero temperatures, a condition where many solid electrolytes struggle.

Why Finding Lithium Is So Difficult

One of the major scientific challenges in this study was figuring out exactly where the lithium ions reside inside the crystal structure. Lithium is the lightest metal and has only three electrons, making it extremely difficult to detect using standard X-ray diffraction techniques. X-rays scatter off electrons, so heavier elements like tantalum dominate the signal, while lithium often becomes almost invisible.

Instead of attempting to detect lithium directly, Kaduk used a logical and indirect approach. First, the positions of the heavier atoms were identified with high precision. Once those were mapped, it became possible to look for empty spaces in the structure where lithium ions could reasonably fit.

Atoms cannot overlap, and crystals must follow strict geometric rules. By systematically narrowing down which voids were large enough and correctly shaped to host lithium ions, Kaduk identified a specific set of sites within the lattice. These sites are positioned close enough together to allow lithium ions to hop easily from one location to another.

Channels That Enable Fast Ion Movement

The final structure revealed something remarkable. The tantalum, oxygen, and chlorine atoms form long, rigid chains that run through the crystal. Between these chains are open channels that act like highways for lithium ions.

Within these channels, lithium occupies tetrahedral and pentahedral sites, which are geometric arrangements that support smooth ion movement. The spacing between these sites is ideal for fast hopping, enabling lithium ions to diffuse efficiently along the length of the material.

This structural feature explains why LTOC demonstrates superionic conductivity, a term used when ions move through a solid almost as freely as they do in a liquid. The presence of these continuous pathways is a major reason why the material performs so well compared to existing solid electrolytes.

Confirming the Structure With Quantum Calculations

After identifying the likely lithium positions, the research team used density functional theory (DFT) calculations to confirm that the proposed structure was physically stable. These quantum mechanical simulations allowed the researchers to optimize the atomic positions and test whether the structure would naturally hold together.

The results showed that the structure remained nearly unchanged after optimization, providing strong evidence that the identified lithium sites were correct. This computational confirmation added confidence to the experimental findings and strengthened the overall conclusions of the study.

Why Low-Temperature Performance Matters

One of the most exciting aspects of LTOC is its ability to conduct lithium ions efficiently at low temperatures. Many current battery technologies suffer dramatic performance losses in cold environments. This is a serious limitation for electric vehicles, grid storage, and outdoor energy systems operating in colder climates.

Because LTOC maintains high conductivity even in the cold, it could help enable solid-state batteries that perform reliably year-round. This property alone makes the material a strong candidate for future commercial applications.

Broader Implications for Battery Design

Beyond this specific material, the study highlights a broader design strategy for solid electrolytes. The idea of engineering the anion sublattice to create open ion pathways could be applied to other material systems as well.

Traditional oxide-based solid electrolytes are often stable but slow, while sulfide-based ones are fast but chemically sensitive. Oxyhalides like LTOC may offer a balanced middle ground, combining stability with high ionic mobility.

This approach opens new possibilities for designing solid electrolytes that are not only fast but also durable, safe, and easier to integrate into practical battery architectures.

A Step Forward, Built on Careful Details

While Kaduk describes his contribution as just one part of a larger collaboration, identifying the lithium positions was a key step in turning experimental observations into a clear scientific explanation. Understanding where ions reside and how they move is essential for rational material design, especially in energy storage research.

The study demonstrates how careful structural analysis, combined with modern computational tools, can reveal insights that directly impact real-world technology.

Looking Ahead

LTOC is still a research material, and further work will be needed to test its long-term stability, scalability, and compatibility with battery electrodes. However, the results presented in this study represent a significant advance in solid-state electrolyte research.

As the push for safer, higher-performing batteries continues, materials like lithium tantalum oxychloride show that progress often comes down to understanding the smallest details — right down to where a single lithium ion sits inside a crystal.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt9678