Could TRAPPIST-1’s Seven Earth-Sized Planets Actually Hold Onto Moons?

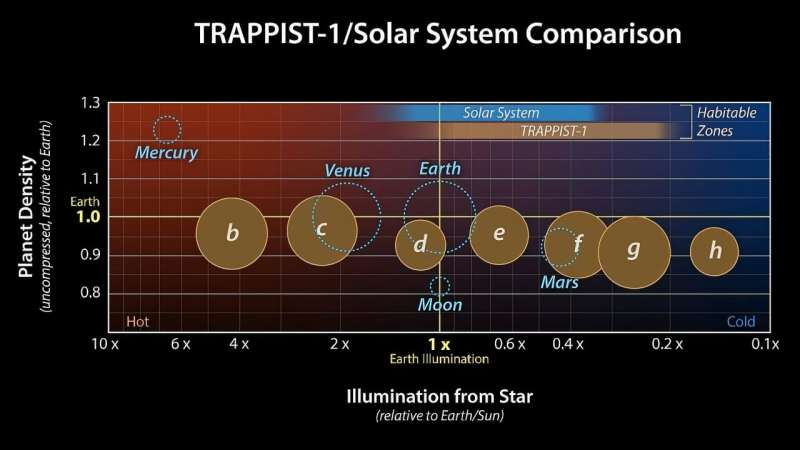

Forty light-years away from Earth, orbiting a faint and cool red dwarf star, lies one of the most fascinating planetary systems ever discovered: TRAPPIST-1. Since its announcement in 2017, this compact system of seven Earth-sized planets has become a favorite among astronomers and space enthusiasts alike. Three of these worlds orbit within the star’s habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist.

But planets alone don’t tell the whole story. A lingering and surprisingly complex question has remained unanswered for years: could any of these tightly packed planets host moons? New research suggests the answer is yes — but only under very specific conditions.

Why Moons in the TRAPPIST-1 System Are a Big Deal

Moons play a major role in shaping planetary environments. In our own solar system, moons influence tides, axial stability, and even geological activity. Earth’s Moon, for example, helps stabilize our planet’s tilt and contributes to long-term climate stability.

So when astronomers consider whether exoplanets might be capable of supporting life, the presence — or absence — of moons matters. The TRAPPIST-1 system, however, poses a unique challenge. Its planets orbit extremely close to their star and to one another, forming a resonant chain where each planet’s orbit is gravitationally linked to the others. This creates a delicate cosmic balancing act.

The New Study Exploring Moon Stability

A new study by Shubham Dey and Sean Raymond, recently posted to the arXiv preprint server, takes a deep dive into this question. The research focuses on the orbital stability of hypothetical moons around each of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets.

To investigate this, the researchers ran thousands of computer simulations. For each planet, they placed 100 virtual moons into circular orbits, starting just outside the Roche limit — the distance where tidal forces from a planet would tear a moon apart — and extending outward toward the planet’s gravitational boundary.

The goal was simple but ambitious: determine where moons could survive for billions of years without being ejected, shattered, or pulled into their host planet.

What Happens When Planets Are Studied in Isolation

The first phase of the simulations treated each TRAPPIST-1 planet as if it were alone, ignoring the gravitational influence of neighboring worlds. Under these idealized conditions, the results aligned neatly with theoretical expectations.

In isolation, moons could remain stable from the Roche limit out to roughly half of a planet’s Hill radius. The Hill radius defines the region where a planet’s gravity dominates over the pull of its star. This finding suggested that, at least on paper, each TRAPPIST-1 planet could host moons without much trouble.

But the TRAPPIST-1 system is anything but isolated.

When Reality Sets In: A Crowded, Resonant System

When the simulations were updated to include all seven planets orbiting together, the picture changed noticeably. The planets of TRAPPIST-1 exist in a tightly packed resonant configuration, meaning their orbits are gravitationally synchronized in a repeating pattern.

This constant gravitational tugging has consequences.

The study found that the presence of neighboring planets compresses the stable moon zone around each world. Instead of extending to half the Hill radius, the outer stability boundary shrank to about 40–45% of the Hill radius once all planets were included.

Interestingly, no single neighboring planet caused a dramatic disruption on its own. Instead, it was the combined gravitational influence of the entire system that produced what researchers describe as a resonant “squeeze.” The effect was most noticeable for TRAPPIST-1 b, the innermost planet, and TRAPPIST-1 e, one of the planets located in the habitable zone.

Still, the news isn’t all bad. Even with this contraction, there remains plenty of orbital real estate close to each planet where moons could survive.

The Bigger Problem: Tidal Forces and Time

Orbital stability is only part of the story. The researchers also examined how tidal interactions between planets and their moons would play out over billions of years.

Tidal forces cause moons to slowly lose orbital energy. Over long timescales, this process can make moons spiral inward and eventually collide with their host planet. In the TRAPPIST-1 system, where planets orbit extremely close to their star, these tidal effects are especially strong.

The simulations revealed a strict upper limit on moon size. To survive for the system’s entire lifetime, moons would need to be extremely small — less than about one ten-millionth of Earth’s mass. That’s vastly smaller than Earth’s Moon and closer in scale to large asteroids.

The outer planets in the system may be able to host slightly more massive moons, but even then, the satellites would still be tiny by solar system standards.

Could Such Moons Actually Exist?

From a theoretical standpoint, the study makes one thing clear: the architecture of the TRAPPIST-1 system does not rule out moons. It simply places very tight constraints on their size and orbital distance.

Whether such moons formed in the first place is another question entirely. Moon formation typically requires material in orbit around a planet, often from massive impacts or leftover debris. In such a compact system, forming and retaining even small moons would be challenging.

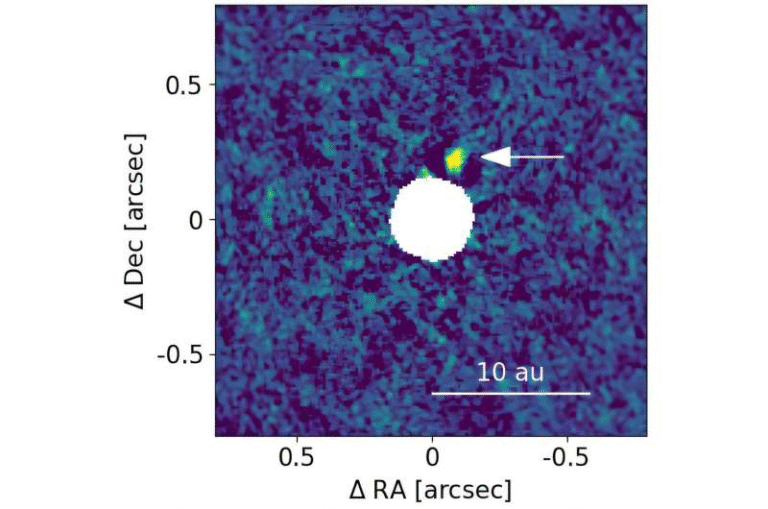

Detecting them is an even bigger hurdle. At a distance of 40 light-years, and given their predicted size, current telescopes simply cannot see these moons. Even advanced instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope are not yet capable of detecting satellites this small.

What This Means for Habitability

While tiny moons may not dramatically affect planetary climates the way Earth’s Moon does, their presence could still influence local tides, orbital dynamics, and possibly subsurface environments. For planets like TRAPPIST-1 e, any additional factor that affects long-term stability is worth paying attention to.

More broadly, this research helps scientists refine their understanding of exoplanet systems very different from our own. Not all planetary systems resemble the spacious layout of the solar system, and TRAPPIST-1 serves as a valuable laboratory for studying extreme planetary configurations.

A Step Forward in Exomoon Science

Even though the study doesn’t confirm the existence of moons around TRAPPIST-1, it provides something just as important: clear theoretical boundaries. It shows that moons are not automatically excluded by tightly packed, resonant planetary systems — but survival requires them to be small, close, and dynamically well-behaved.

As observational technology improves, these predictions will serve as a roadmap for future searches. One day, we may be able to test whether these tiny companions are quietly circling their planets, hidden within one of the most intriguing star systems we’ve ever discovered.

Research Paper:

Orbital Stability of Moons Around the TRAPPIST-1 Planets – Shubham Dey & Sean N. Raymond

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.19226