Solar Flares and Stellar Flares Hit Differently Than Scientists Expected

The Sun is our closest star, and because of that, it is also the one we understand best. For centuries, astronomers have watched it carefully, tracking its behavior, its cycles, and its occasional outbursts. One of the most dramatic of these outbursts is the solar flare, a sudden release of energy that can send radiation and charged particles racing toward Earth. For a long time, scientists assumed that other stars behave in much the same way as our Sun. A new study suggests that this assumption may be wrong, at least when it comes to how flares work.

Researchers have now found that stellar flares on most stars do not follow the same rules as solar flares on the Sun. In fact, the Sun appears to be something of an oddball among stars.

What We Know About the Sun and Its Flares

The Sun is not a static, unchanging ball of gas. It goes through periods of higher and lower activity, driven by its magnetic field. Roughly every 11 years, the Sun transitions from a quiet phase to a more active one and back again. During active periods, dark regions known as sunspots appear on its surface more frequently.

Sunspots are cooler areas created by intense magnetic fields. These same magnetic fields are also responsible for solar flares. As a result, solar flares and sunspots are closely connected. When astronomers observe a solar flare, they almost always find sunspots in the same region of the Sun at the same time. This tight relationship has shaped how scientists think about stellar activity in general.

For decades, it seemed reasonable to assume that other main-sequence stars—stars that fuse hydrogen like the Sun—would show the same pattern.

Starspots and Activity Cycles on Other Stars

Observing other stars in detail is far more difficult than studying the Sun. We cannot directly see starspots on most stars because they are so far away. Still, astronomers have managed to study starspot activity on about 400 stars using indirect methods.

These observations show that many stars do have activity cycles similar to the Sun’s, although the length of these cycles can vary widely, from three years to as long as 20 years. Spectral data also reveal that magnetic activity rises and falls along with these cycles, much like it does on the Sun.

Given that flares are driven by magnetic fields, scientists expected stellar flares to line up neatly with starspots, just as solar flares do with sunspots. This expectation turns out to be largely incorrect.

How Scientists Studied Stellar Flares at Scale

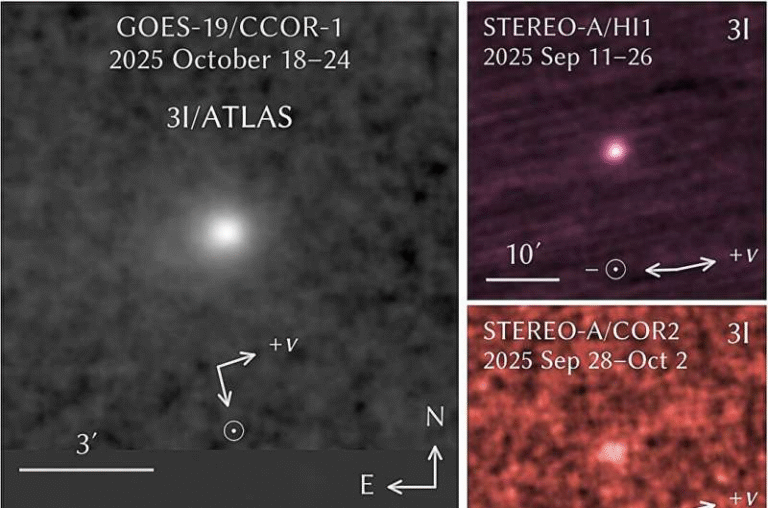

Because direct imaging of starspots is impractical for large samples of stars, researchers turned to data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Although TESS was designed to search for exoplanets, it also provides extremely precise measurements of stellar brightness over time.

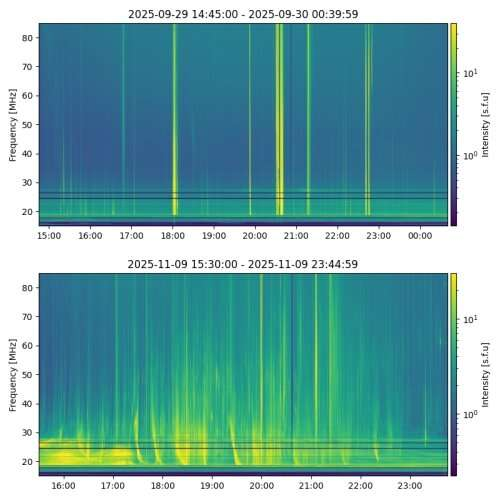

The method is clever and indirect. When a star has many starspots, its brightness changes slightly as it rotates. The star appears dimmer when the spots face Earth and brighter when they rotate out of view. This creates a repeating pattern in the star’s light curve. Stellar flares, on the other hand, show up as sudden, sharp spikes in brightness.

Because flares can only be seen on the side of the star facing us, researchers can compare the timing of flares with the star’s brightness pattern to see whether flares occur when starspots are likely present.

A Massive Dataset With a Surprising Result

Using TESS data, the research team analyzed more than 14,000 stars and identified over 200,000 stellar flares. This is one of the largest datasets ever used to study stellar flare behavior.

If stars behaved like the Sun, the results should have been clear. Flares would mostly occur when starspots were facing Earth. That is exactly what happens with solar flares.

Instead, the researchers found something unexpected. For most stars, stellar flares were only associated with starspots about half of the time. In other words, when a flare was observed, the chance that starspots were present on the visible side of the star was essentially random.

There was no strong correlation at all between starspots and flares for the majority of stars studied.

Why the Sun Appears to Be an Exception

This finding suggests that the Sun may be unusual. On our star, sunspots and solar flares are tightly linked. On most other stars, they are not.

The study implies that the physical mechanisms driving flares and spots may differ from star to star. While the Sun’s flares seem to arise mainly from magnetic regions associated with sunspots, other stars may generate flares through magnetic processes that are less tied to large, visible starspots.

Why the Sun behaves this way is still an open question. Scientists do not yet understand what makes the Sun’s magnetic field so effective at linking spots and flares, or why this link appears to be weaker or absent in many other stars.

Why This Matters for Astronomy and Space Science

These results challenge a long-standing assumption in stellar physics: that the Sun is a typical example of how stars behave. If the Sun is actually an outlier when it comes to flare activity, scientists may need to rethink how they model stellar magnetism.

This also affects how astronomers think about space weather around other stars. Stellar flares can have a major impact on nearby planets, potentially stripping atmospheres or affecting habitability. If flares do not reliably occur near starspots, predicting stellar activity becomes more difficult.

Extra Context: What Are Stellar Flares, Really?

Stellar flares are powerful bursts of energy caused by magnetic reconnection, a process where twisted magnetic field lines suddenly snap and realign. This releases enormous amounts of energy in the form of light, radiation, and energetic particles.

Some stars, especially younger or faster-rotating ones, produce superflares that are far more energetic than anything the Sun has ever produced. Understanding where and how these flares occur is crucial for understanding stellar evolution and the environments of exoplanets.

The new findings suggest that flare behavior is more diverse than previously thought, and that solar-based models may not apply universally.

Extra Context: Why TESS Is So Useful for This Research

TESS continuously monitors large sections of the sky, recording brightness changes for thousands of stars at once. This makes it uniquely suited for statistical studies like this one. While individual stellar flares have been studied before, TESS allows astronomers to analyze flare behavior across entire stellar populations, revealing patterns that would otherwise remain hidden.

What Comes Next

The study raises more questions than it answers. Why does the Sun show such a strong flare–spot correlation when most stars do not? Are there specific types of stars that behave more like the Sun? How do age, rotation speed, and magnetic structure influence these differences?

Future observations, combined with improved models of stellar magnetic fields, may help explain why solar flares and stellar flares truly hit differently.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.01051