Astronomers Reveal the Hidden Lives of the Early Universe’s Ultramassive Galaxies

Astronomers have taken a deeper look into the early universe and uncovered something surprising about its most enormous galaxies. Using a powerful combination of ground-based and space-based telescopes, an international research team has shown that ultramassive galaxies—systems containing more than 100 billion stars—did not all evolve in the same way. Even when observed at nearly the same cosmic time, these galaxies followed very different evolutionary paths, challenging long-standing assumptions about how the biggest galaxies in the universe formed and shut down their star formation.

The study focuses on galaxies seen less than 2 billion years after the Big Bang, a period when the universe was still young and rapidly evolving. At that stage, astronomers generally expected most extremely massive galaxies to still be actively forming stars. Instead, the new observations reveal a more complex picture: some of these giants had already stopped forming stars and lost much of their dust, while others were still vigorously forming stars but were heavily hidden behind thick layers of cosmic dust.

Understanding this difference is critical because dust can easily fool astronomers. Galaxies rich in dust can appear red and inactive when viewed only in optical or near-infrared light, making them look similar to truly “dead” galaxies. This overlap has made it difficult for decades to confidently identify genuinely quiescent galaxies in the early universe.

The breakthrough came from combining observations across a wide range of wavelengths. By analyzing data from optical, near-infrared, far-infrared, submillimeter, and radio telescopes, the researchers were able to separate galaxies that were truly inactive from those that were still forming stars but obscured by dust. This multi-wavelength strategy revealed that a significant fraction of ultramassive galaxies at high redshift were already genuinely quiescent, an unexpected result given their size and age.

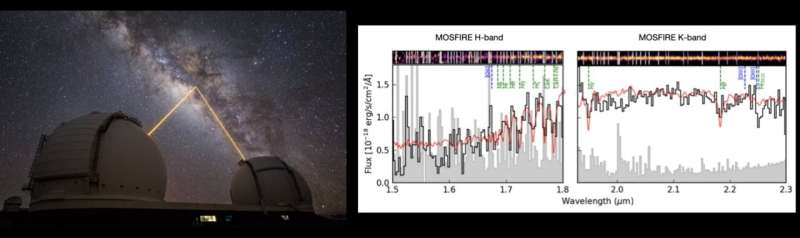

The research is part of the MAGAZ3NE survey (MAssive Galaxies at z ~ 3 NEar-infrared Survey), a long-running international collaboration designed to study how the universe’s most massive galaxies formed and evolved. MAGAZ3NE focuses on galaxies at redshifts around z ≈ 3, corresponding to a time when the universe was only a fraction of its current age.

A major component of this work involved more than 30 nights of spectroscopy from the W. M. Keck Observatory. The team used the MOSFIRE instrument (Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration), which allowed them to measure precise redshifts and stellar masses for these distant galaxies. These measurements were essential for determining how massive the galaxies really are and where they fit in cosmic history.

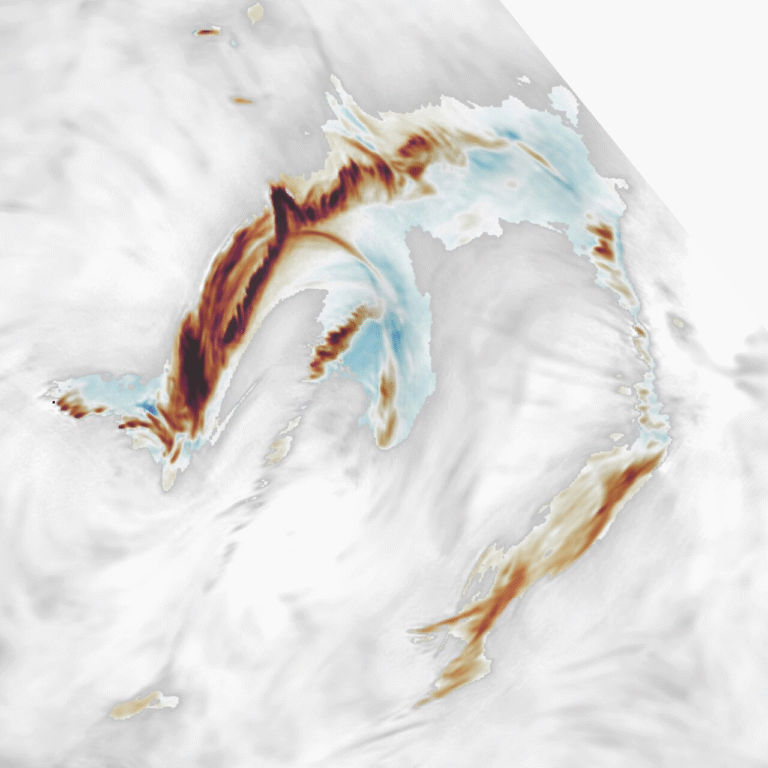

To uncover hidden star formation, the Keck data were combined with observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). ALMA, in particular, plays a crucial role because it observes far-infrared and submillimeter wavelengths that trace cold dust and obscured star formation. If a galaxy is still actively forming stars but buried in dust, ALMA can detect the thermal emission from that dust even when optical telescopes cannot.

This approach revealed striking diversity among galaxies with similar stellar masses at the same epoch. Most of the ultramassive galaxies in the sample turned out to be truly quiescent, meaning their star formation had already shut down efficiently and rapidly. Several of these systems are also among the most dust-poor massive galaxies ever identified at such early times, suggesting that whatever processes stopped their star formation were extremely effective at removing or destroying dust as well.

However, not all galaxies in the sample fit this pattern. Two systems still show measurable dust emission. One of them appears to host ongoing star formation that is heavily obscured, while the other seems to be caught mid-transition, actively quenching its star formation. Together, these galaxies offer a rare snapshot of different evolutionary stages within a very short cosmic time window.

These findings challenge the idea that massive galaxies all shut down star formation in the same way or on the same timeline. Instead, the results suggest that quenching is neither uniform nor simple, even for the most massive systems in the universe. This has important implications for theoretical models of galaxy formation, which must now account for multiple pathways leading to quiescence at very early times.

Why does this matter for our understanding of the universe today? Massive galaxies dominate the structure of the modern universe, and their histories influence everything from galaxy clusters to the distribution of heavy elements. If ultramassive galaxies were already quiescent when the universe was young, it means they formed their stars extremely quickly and shut down star formation far earlier than many models predict.

This research also highlights the limitations of relying on a narrow range of observations. Optical and near-infrared data alone can dramatically underestimate star formation in dusty galaxies, leading to misclassification. The study demonstrates that multi-wavelength observations are essential for building a complete and accurate picture of galaxy evolution, especially in the distant universe.

Beyond the specific findings, the work underscores how rare and valuable these ultramassive galaxies are as laboratories for studying cosmic history. By combining data from some of the world’s most powerful telescopes, astronomers can probe not only how these galaxies look, but also how they grow, evolve, and eventually shut down.

Looking ahead, future observations—particularly with next-generation facilities and continued ALMA studies—will help refine these results and expand the sample size. As more ultramassive galaxies are studied in detail, astronomers will be able to better determine which physical processes drive early quenching, such as feedback from supermassive black holes, rapid gas depletion, or environmental effects.

In the broader context of modern astronomy, this study fits into a growing body of evidence showing that the early universe was far more diverse and dynamic than once thought. Rather than following a single, orderly path, even the largest galaxies experienced multiple evolutionary routes, leaving behind the complex cosmic landscape we observe today.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.08460