Cosmic Lens Reveals Hyperactive Cradle of a Future Galaxy Cluster

Galaxy clusters are the largest gravitationally bound structures in the universe, formed by hundreds or even thousands of galaxies packed tightly together. Studying how these enormous structures come into existence has long been a challenge for astronomers, mainly because their earliest stages are distant, faint, and often hidden behind thick clouds of cosmic dust. A recent discovery, however, has opened an unusually clear window into this early phase of cluster formation, thanks to a fortunate alignment of galaxies and the natural magnifying power of gravity.

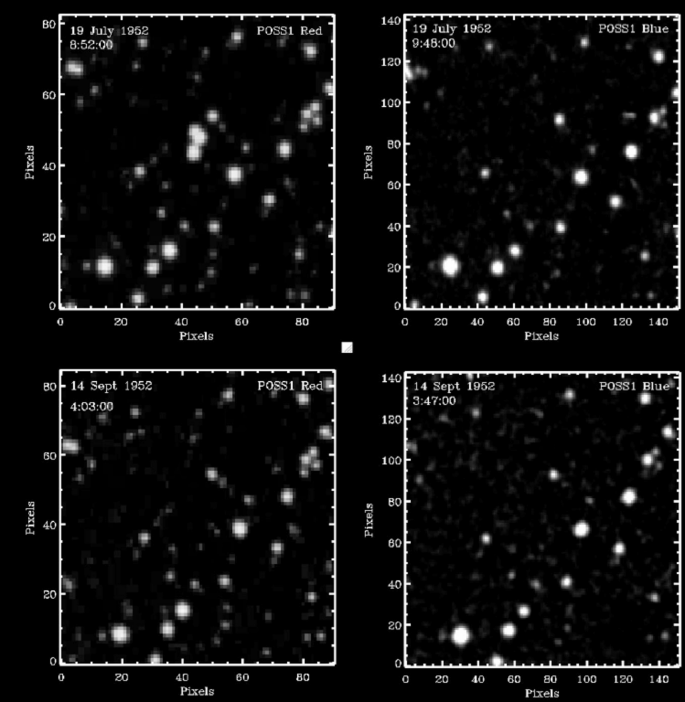

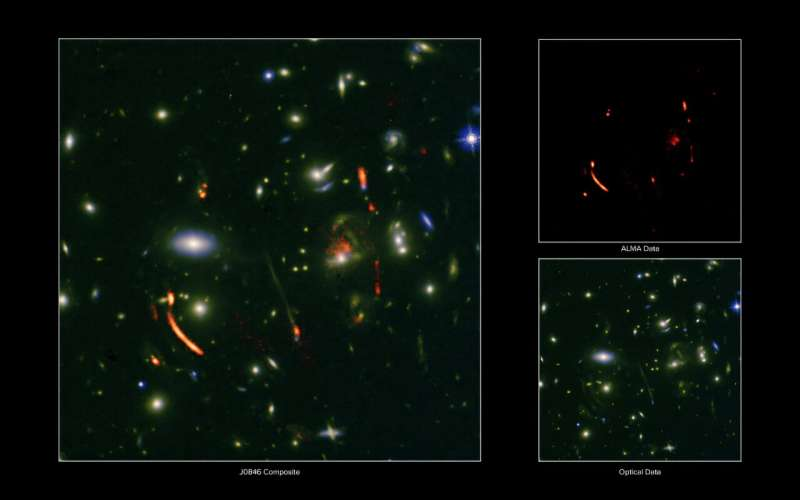

Astronomers using the U.S. National Science Foundation Very Large Array (VLA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have identified an exceptionally rare object: a strongly lensed protocluster core, known as PJ0846+15, or simply J0846. This system shows a tightly packed group of young, rapidly growing galaxies as they appeared more than 11 billion years ago, when the universe was only a few billion years old.

A Rare Look at a Protocluster in Its Infancy

Galaxy clusters do not form overnight. Their earliest ancestors, called protoclusters, represent regions where galaxies are just beginning to gather under the influence of gravity. Observing these early environments allows scientists to understand how galaxies grow, interact, and eventually settle into the massive clusters we see today.

What makes J0846 special is that it is the first known protocluster core discovered through strong gravitational lensing. In simple terms, a massive galaxy cluster located roughly halfway between Earth and J0846 bends and magnifies the light coming from the distant system behind it. This foreground cluster acts as a cosmic lens, stretching the background galaxies into bright arcs and dramatically boosting their apparent brightness and size.

Without this lensing effect, J0846 would likely be too faint and compact to study in such detail. Instead, astronomers are able to examine one of the most intense early cluster-building environments ever observed.

From a Single Blur to Eleven Distinct Galaxies

Before ALMA took a closer look, J0846 appeared as a single bright submillimeter source in data from the Planck satellite. High-resolution ALMA observations revealed a very different picture. That single source is actually a dense concentration of at least 11 dusty, star-forming galaxies, all packed into a region smaller than the distance between the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies.

All of these galaxies share a common redshift, confirming that they are physically associated and not just aligned by chance. This compact grouping makes J0846 one of the fastest-growing protocluster cores known so far.

Each of these galaxies is undergoing an intense starburst phase, forming stars at extraordinary rates. At this point in cosmic history, these galaxies are rapidly building up the stellar mass that will eventually define the massive galaxies found in modern-day clusters.

Why Dust Matters in the Early Universe

One reason protoclusters like J0846 are difficult to detect is dust. These young galaxies contain large amounts of dust that absorb visible light, making them nearly invisible to optical telescopes. While this dust hides the galaxies from view, it also plays a crucial role in star formation by cooling gas and helping it collapse into new stars.

This is where ALMA excels. By observing submillimeter wavelengths, ALMA can detect the faint glow of cold dust and molecular gas. In J0846, ALMA mapped both the dust continuum emission and CO(3–2) molecular gas lines, allowing astronomers to measure gas masses, star formation rates, and internal motions within the galaxies.

The results show enormous reservoirs of cold gas, providing the raw material for rapid star formation. These gas supplies explain how the protocluster is growing so quickly and why it represents such an extreme environment.

A Unique Double-Cluster Alignment

J0846 is not just interesting because of its distance or activity. Its geometry makes it especially valuable for science. The system sits behind a massive foreground galaxy cluster, creating a rare double-cluster alignment along nearly the same line of sight.

The foreground cluster is much closer to Earth and represents a more mature stage of cluster evolution, while the background protocluster shows an early stage of assembly. This alignment allows astronomers to observe two different epochs of cluster development simultaneously, almost like looking through a forest where mature trees stand in front of tiny saplings.

The gravitational lensing caused by the foreground cluster not only magnifies the background galaxies but also distorts and, in some cases, duplicates their images. This effect provides valuable information about the mass distribution, including dark matter, within the lensing cluster.

What the VLA Adds to the Picture

While ALMA focuses on dust and molecular gas, the Very Large Array contributes another important layer of information. Observations at 6 GHz radio frequencies trace radio emission associated with star formation and possible active galactic nuclei.

The VLA data help astronomers identify radio counterparts to the lensed background galaxies and study the structure of galaxies in the foreground cluster. Together, ALMA and VLA observations create a multi-wavelength view of both the protocluster and the lensing system, tying star formation activity to the underlying gravitational framework.

Why This Discovery Matters for Galaxy Evolution

Protoclusters like J0846 are the construction sites of the universe’s largest structures. By studying them, astronomers can test theories of how galaxies evolve in dense environments, how gas is funneled into star formation, and how dark matter shapes cosmic architecture.

The extreme activity seen in J0846 suggests that some galaxy clusters may build a significant fraction of their mass very early in cosmic history. This challenges simpler models where cluster growth happens more gradually over time.

Because J0846 is both strongly lensed and exceptionally compact, it serves as a benchmark system. Future observations with ALMA, the VLA, and upcoming telescopes will likely use it as a reference point for connecting early, dust-rich protoclusters to the massive, relatively quiet clusters observed in the present-day universe.

Extra Context: Why Protoclusters Are So Important

Protoclusters are rare because they occupy brief phases of cosmic time. They are regions where gravity, gas, galaxies, and dark matter are all interacting intensely. Studying them helps answer key questions, such as:

- How quickly do galaxies grow in dense environments?

- When do galaxy clusters assemble most of their mass?

- How does environment influence star formation and galaxy structure?

Strongly lensed systems like J0846 are especially valuable because lensing effectively boosts the power of our telescopes, allowing us to study details that would otherwise remain inaccessible.

Looking Ahead

As observational techniques improve and surveys expand, astronomers expect to find more systems like J0846. Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how the universe’s largest structures came to be. For now, J0846 stands out as a rare and powerful glimpse into the hyperactive early life of a future galaxy cluster, revealed by the fortunate alignment of cosmic matter and the bending of light across billions of years.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adf4d5