Study Offers a Possible Solution to the Gravitational Wave Background Mystery

Scientists studying the universe’s deepest signals may be closer to solving one of astrophysics’ most intriguing puzzles: why the gravitational wave background is stronger than expected. A new study led by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder suggests that the answer lies in how supermassive black holes grow during galaxy mergers, especially the smaller ones that were long overlooked.

The gravitational wave background refers to a constant, low-level sea of gravitational waves flowing through the universe. These waves are ripples in space and time created by some of the most violent events in the cosmos, particularly the mergers of galaxies and the supermassive black holes at their centers. While individual gravitational wave events can be detected from dramatic collisions, this background is more like a cosmic hum, formed by the overlapping signals of countless mergers happening across billions of years.

In 2023, several international collaborations, including the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav), announced the first convincing detection of this background using pulsars—ultra-precise cosmic clocks scattered throughout the galaxy. The discovery was a major milestone. However, it came with a surprise: the signal appeared much stronger than existing theoretical models predicted.

That discrepancy sparked a wave of questions. Were scientists missing a key source of gravitational waves? Or was there something incomplete in how galaxy mergers and black hole growth were being modeled?

The new study, published in The Astrophysical Journal, offers a compelling explanation.

Why Galaxy Mergers Matter for Gravitational Waves

At the heart of most galaxies sits a supermassive black hole, with masses ranging from millions to billions of times that of the Sun. When galaxies merge—a process that is extremely common over cosmic history—their central black holes don’t collide immediately. Instead, they form a binary system, orbiting each other for millions or even billions of years before finally merging.

As these black holes spiral closer together, they emit gravitational waves. The combined effect of countless such systems across the universe produces the gravitational wave background detected by experiments like NANOGrav.

For years, models assumed that larger black holes dominated this background. Smaller supermassive black holes were considered relatively unimportant, contributing only weakly to the overall signal. This assumption shaped predictions about how strong the background should be.

But according to the new research, that assumption may have been incomplete.

The Role of Preferential Accretion

The study was led by Julie Comerford, a professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at CU Boulder, with co-author Joseph Simon, a former postdoctoral researcher at the university. Their work focuses on a process known as preferential accretion, which occurs during galaxy mergers.

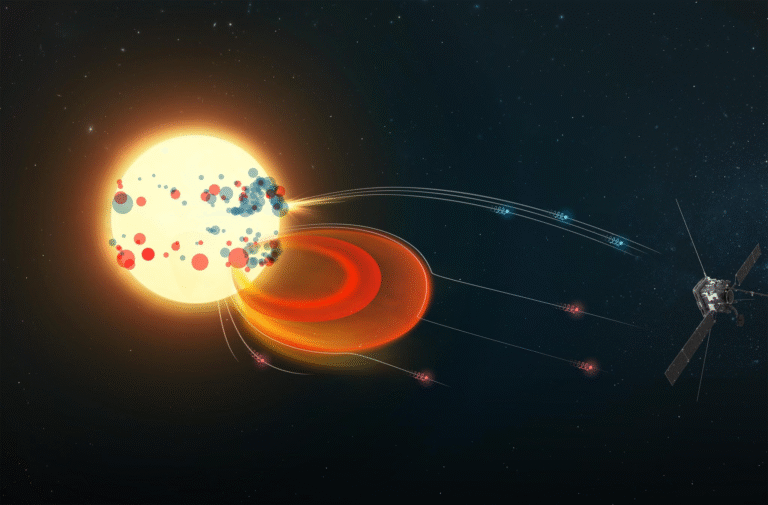

When two galaxies collide, vast amounts of gas are disturbed and funneled toward their centers. This gas often forms a thick, doughnut-shaped structure around the merging black holes. Both black holes can feed on this gas, growing in mass over time—but not equally.

Previous simulations hinted at something unexpected: the smaller black hole in a merging pair may actually be better positioned to accrete gas. While the larger black hole tends to sit closer to the center of the gas structure, where less material is available, the smaller one orbits farther out, closer to denser gas regions. As a result, the smaller black hole can grow faster than its larger companion.

This uneven growth changes the dynamics of the merger in an important way.

Why Size Ratios Change Everything

Gravitational wave strength depends heavily on the mass ratio of the two merging black holes. When one black hole is much smaller than the other, the resulting gravitational waves are weaker. When the masses are closer in size, the signal becomes significantly stronger.

Comerford and Simon developed a detailed theoretical framework describing how galaxies and their black holes merge over cosmic time. They then introduced a key adjustment: allowing the smaller black hole in a merging pair to grow about 10% more than the larger one due to preferential accretion.

That relatively modest change had a major effect. Once this growth imbalance was included, predictions for the gravitational wave background closely matched the larger-than-expected signal observed by NANOGrav.

In other words, black holes that start out small can bulk up during mergers, making their final collisions far more powerful sources of gravitational waves than previously assumed.

Rethinking the Importance of Smaller Black Holes

One of the most significant implications of the study is that smaller supermassive black holes should not be ignored when modeling the gravitational wave background. Over billions of years, these objects may play a much larger role than scientists once thought.

This finding also reshapes how researchers classify galaxy mergers. Events once considered “minor mergers,” involving a large galaxy and a much smaller one, may actually behave more like major mergers if the smaller black hole grows rapidly before the final collision.

That shift could help explain why the universe’s gravitational wave background is louder than expected without requiring exotic new physics or unknown sources.

What This Means for Future Observations

While the study offers a strong theoretical explanation, it does not claim to fully close the case. The researchers emphasize that more observational evidence is needed.

Comerford’s team has begun a new effort to observe real galaxies in the process of merging, looking for signs that preferential accretion occurs as predicted. Confirming this behavior in actual systems would strengthen the case that black hole growth during mergers is a key driver of the gravitational wave background.

The findings also have implications beyond pulsar timing arrays. Future observatories such as LISA (the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), which will detect gravitational waves at different frequencies, could benefit from improved models of black hole growth and merger histories.

A Broader Puzzle About Black Hole Origins

This research connects to a much larger question in astrophysics: how supermassive black holes form in the first place. Observations of the early universe reveal massive black holes existing surprisingly soon after the Big Bang, and scientists still do not fully understand how they grew so large so quickly.

Preferential accretion during mergers could be one piece of that puzzle. If smaller black holes consistently gain mass more efficiently, it may help explain how early, relatively small black holes evolved into the giants seen today.

Understanding the Gravitational Wave Background

The gravitational wave background itself is a relatively new frontier in astronomy. Unlike individual gravitational wave detections, which appear as short-lived signals, the background is detected statistically, by looking for subtle correlations in the timing of pulsars spread across the sky.

As detection methods improve and theoretical models become more refined, scientists expect the gravitational wave background to become a powerful tool for studying galaxy evolution, black hole demographics, and the large-scale structure of the universe.

This new study shows that even small adjustments to our understanding of black hole physics can have far-reaching consequences.

By paying closer attention to the growth of smaller black holes, researchers may have found a missing ingredient that helps align theory with observation—and brings us one step closer to understanding how the universe’s most massive objects shape the fabric of space and time.

Research paper:

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ae1133