Tiny Mars’s Big Impact on Earth’s Climate and How the Red Planet Helps Shape Ice Ages

Mars is often described as a small, dry, and distant neighbor, a planet that feels more like a background character in the solar system than a major influencer. After all, it is about half the size of Earth and has just one-tenth of Earth’s mass. Compared to giants like Jupiter or even closer neighbors like Venus, Mars seems almost insignificant. But new scientific research suggests that this assumption is deeply misleading. Despite its size, Mars plays a measurable and surprisingly important role in shaping Earth’s long-term climate, including the rhythms that control ice ages.

This research, led by planetary astrophysicist Stephen Kane of the University of California, Riverside, explores how Mars subtly tugs on Earth’s orbit over vast spans of time. The findings show that without Mars, some of Earth’s most important climate cycles would simply not exist.

How Scientists Study Earth’s Long-Term Climate Cycles

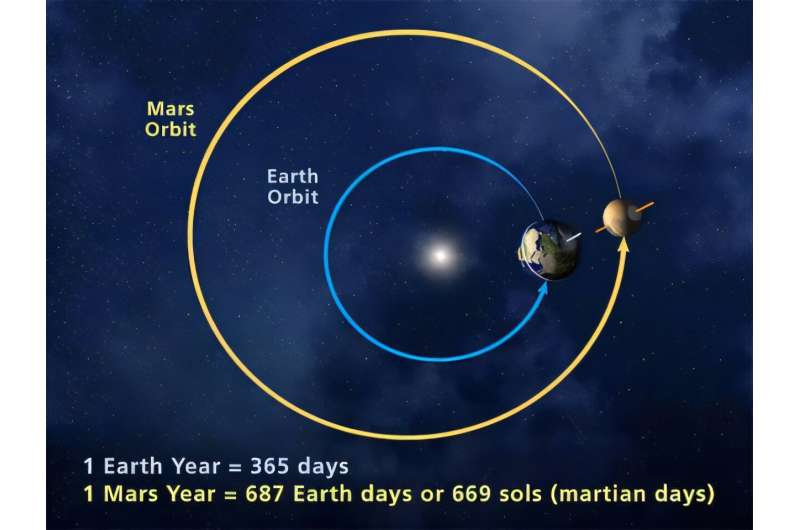

Earth’s climate does not change randomly. Over tens of thousands to millions of years, it follows repeating patterns driven by slow variations in our planet’s orbit and orientation in space. These patterns are known as Milankovitch cycles, named after Serbian scientist Milutin Milankovitch, who first linked orbital mechanics to long-term climate change.

Milankovitch cycles describe changes in three key aspects of Earth’s motion:

- Eccentricity, or how circular or stretched Earth’s orbit around the Sun is

- Obliquity, the tilt of Earth’s rotational axis

- Precession, the gradual wobble of Earth’s axis over time

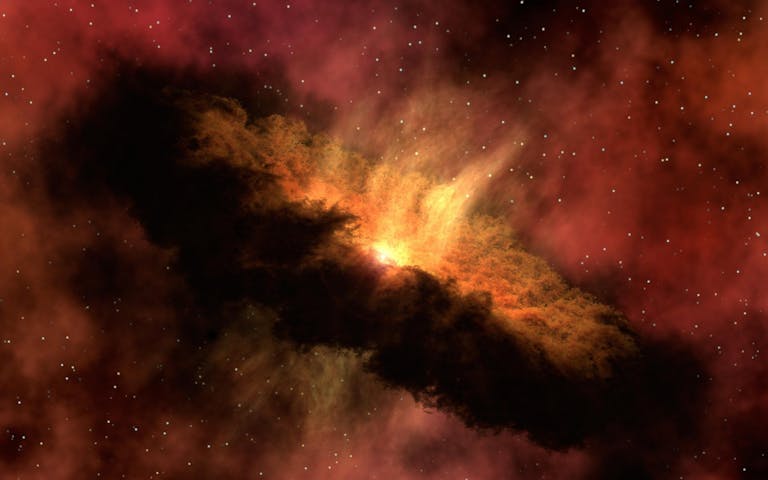

Together, these cycles determine how much sunlight reaches different parts of the planet, which strongly influences the advance and retreat of massive ice sheets. Earth has experienced at least five major ice ages during its 4.5-billion-year history, with the current one beginning around 2.6 million years ago and continuing today.

Questioning Mars’s Role in Earth’s Climate

Previous studies suggested that Mars might be linked to certain patterns seen in ancient ocean sediments, which appear to record climate cycles influenced by planetary gravity. Kane initially approached these claims with skepticism. Mars is small and far away, so it seemed unlikely that its gravity could leave a clear fingerprint in Earth’s geological record.

To test this, Kane ran detailed computer simulations of the solar system, modeling how Earth’s orbit and tilt evolve over extremely long timescales. These simulations allowed him to compare Earth’s behavior under different conditions: with Mars present, with Mars removed, and with Mars having different masses.

What Happens When Mars Is Removed

The results were striking. One well-known Milankovitch cycle, which lasts about 430,000 years, remained unchanged even when Mars was removed from the simulations. This cycle is driven mainly by the gravitational influence of Venus and Jupiter, and it controls long-term changes in the shape of Earth’s orbit.

However, two other major cycles told a very different story.

When Mars was removed entirely, a 100,000-year cycle and a much longer 2.3-million-year cycle vanished completely. These cycles play a major role in variations of Earth’s orbital eccentricity and axial behavior. In simple terms, without Mars, Earth’s climate rhythm would lose some of its most important beats.

Even more revealing, when the mass of Mars was artificially increased in the simulations, these cycles did not disappear. Instead, they became shorter and more frequent, showing that Mars’s gravity directly controls their timing.

Why Mars Has Such a Strong Effect

One of the most surprising aspects of the study is why Mars’s influence is so noticeable. Planets closer to the Sun are more tightly dominated by solar gravity. Mars, being farther out, is less constrained in this way, allowing its gravitational pull to have a broader effect on neighboring planets.

In other words, Mars punches above its weight. Despite its small size, its position in the solar system allows it to exert a meaningful tug on Earth over millions of years.

Mars and the Stability of Earth’s Tilt

Another unexpected finding involves Earth’s axial tilt, which currently sits at about 23.5 degrees. This tilt is responsible for the seasons and plays a crucial role in climate stability.

The simulations showed that increasing Mars’s mass slowed down the rate at which Earth’s tilt changes, effectively stabilizing it. While Mars is not the dominant force controlling Earth’s obliquity, it clearly contributes to how steadily that tilt evolves over time. Subtle changes in tilt can significantly alter how sunlight is distributed across the planet, influencing long-term climate patterns and ice coverage.

Why This Matters for Earth’s History

Climate cycles driven by Milankovitch variations are not just abstract orbital mechanics. They have had real consequences for life on Earth. During glacial periods, forests contracted while grasslands expanded. These environmental shifts are believed to have influenced key evolutionary developments, including upright walking, tool use, and social cooperation in early humans.

If Mars were not part of the equation, Earth’s orbit would lack some of these major cycles. That raises a fascinating question: How different would life on Earth be without Mars? The planet’s quiet gravitational pull may have helped shape not just ice ages, but the evolutionary paths that eventually led to modern humans.

Implications Beyond Our Solar System

This research also has important implications for the search for life beyond Earth. When astronomers discover Earth-sized planets in the so-called habitable zone of distant stars, they often focus on that planet alone. Kane’s work suggests this approach may be incomplete.

Small outer planets in a planetary system could quietly influence the climate stability of potentially habitable worlds, just as Mars does for Earth. Even a modest planet, if positioned correctly, might help regulate orbital cycles in ways that support long-term habitability.

A New Way of Thinking About Planetary Influence

Traditionally, Jupiter and Saturn have been viewed as the dominant architects of the solar system’s structure, with smaller planets playing minor roles. This study challenges that idea by showing how even relatively small planets can leave lasting imprints on climate and habitability.

Mars may appear quiet and lifeless today, but over geological time, it has been an active participant in shaping Earth’s environment. Its gravitational presence has helped define the cycles that govern ice ages, climate shifts, and possibly even evolutionary milestones.

As scientists continue to refine models of planetary systems, Mars serves as a reminder that size alone does not determine significance. Sometimes, the most important influences are the ones working silently in the background for millions of years.

Research paper:

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1538-3873/ae2800