How Astronauts Will Fix Their Gear Using Thin Air

Additive manufacturing, better known as 3D printing, has long been seen as a key technology for future space exploration. When astronauts are months away from Earth, the ability to manufacture tools, replacement parts, and structural components on demand can be the difference between a minor inconvenience and a mission-ending failure. A new research study now suggests that astronauts on Mars may be able to repair and fabricate metal components using something that already surrounds them: the Martian atmosphere itself.

At the center of this idea is a metal 3D-printing technique called Selective Laser Melting (SLM). SLM is widely used on Earth to produce strong, complex metal parts by melting layers of metal powder with a high-powered laser. One of the most common materials used in this process is 316L stainless steel, a durable and corrosion-resistant alloy found in everything from medical equipment to industrial machinery. The new research explores how this exact process could be adapted for use on Mars, without relying on expensive imported gases from Earth.

Why Metal 3D Printing Needs Shield Gases

Metal 3D printing is not as simple as melting metal powder and letting it cool. When metal is heated to extremely high temperatures, it reacts easily with oxygen. On Earth, the oxygen in the atmosphere causes molten metal to oxidize, which weakens the final product and can make it brittle or unusable. To prevent this, metal 3D printers use what is known as a shield gas—a gas that surrounds the printing area and pushes oxygen away from the molten metal.

On Earth, the most common shield gas used in SLM is argon. Argon is a noble gas, meaning it is chemically inert and does not react with molten metal. It does its job extremely well, but it has one major drawback: it is expensive. Even worse for Mars missions, argon is rare on Mars and would need to be transported from Earth in pressurized tanks, adding significant mass, complexity, and cost to any long-term mission.

This is where the new research becomes especially interesting.

Using Mars’ Atmosphere as a Shield Gas

The study, conducted by Zane Mebruer and Wan Shou from the University of Arkansas, examines whether Mars’ atmosphere—made up of roughly 95% carbon dioxide (CO₂)—could be used as an alternative shield gas for metal 3D printing. At first glance, this seems like a bad idea. Carbon dioxide contains oxygen, and the entire purpose of a shield gas is to keep oxygen away from the molten metal.

However, the researchers suspected that the situation might be more nuanced. Mars has an extremely thin atmosphere, and the chemical behavior of gases at the intense temperatures created by an SLM laser is very different from what we experience under normal conditions on Earth.

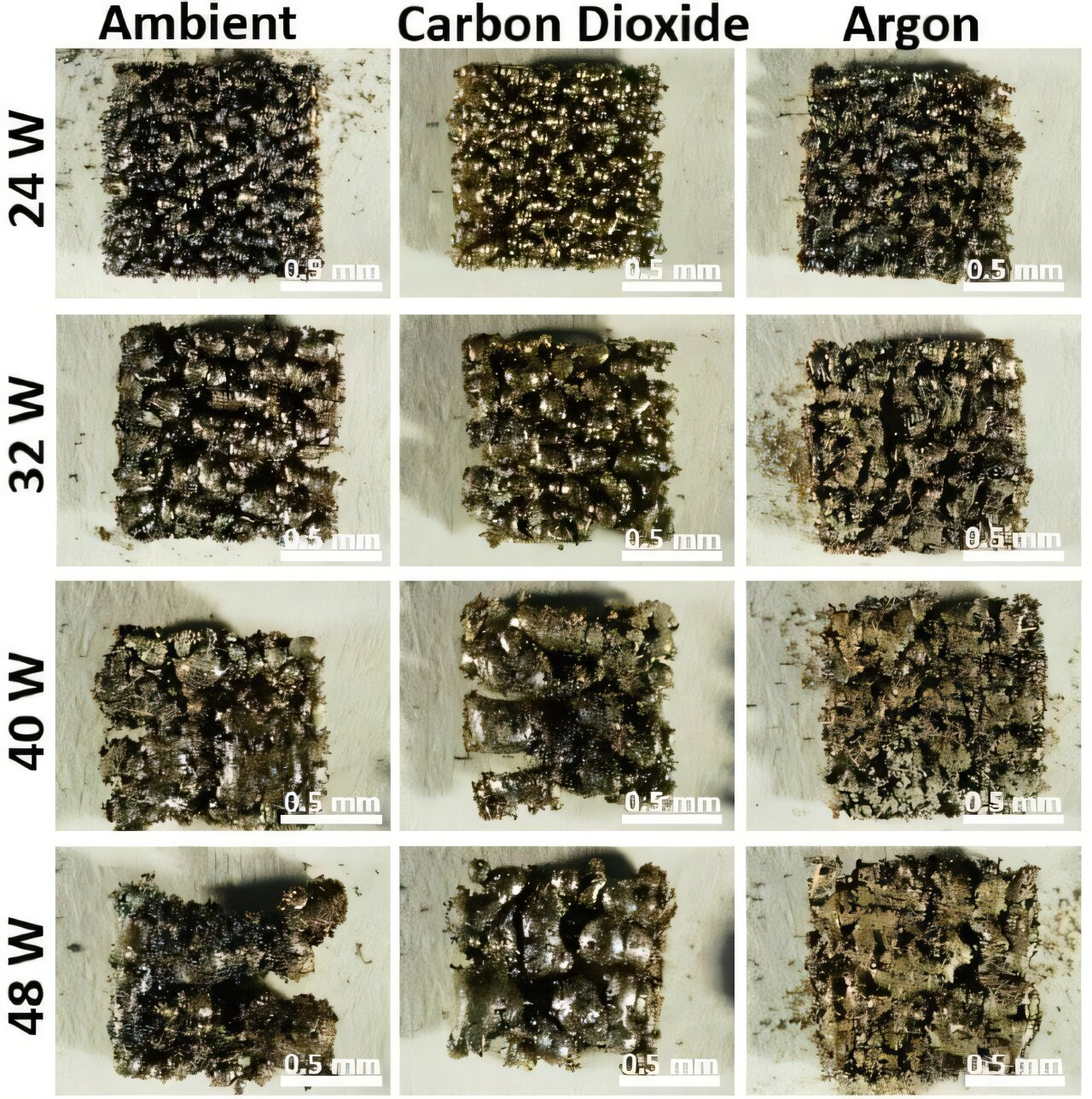

To test this idea, the researchers ran a series of controlled experiments using three different atmospheres during the SLM process:

- Pure argon

- Pure carbon dioxide

- Normal Earth air

Each atmosphere was used to print test samples of 316L stainless steel, allowing the researchers to directly compare performance, structural integrity, and oxidation effects.

What the Experiments Revealed

The results showed a clear hierarchy in performance—but also delivered a surprise.

When argon was used as the shield gas, the printed metal performed exactly as expected. The parts maintained their shape extremely well, with about 98% area retention, meaning the printed layers closely matched their intended geometry.

Carbon dioxide did not perform quite as well, but it came surprisingly close. Parts printed in a CO₂ atmosphere showed around 85% area retention. While not suitable for high-precision or safety-critical components, this level of performance is more than adequate for non-critical infrastructure parts such as hinges, brackets, door handles, or tool components.

Printing in normal Earth air produced predictably poor results. With less than 50% area retention, the parts were severely oxidized and structurally compromised, making them essentially useless.

Why Carbon Dioxide Works Better Than Expected

The key to carbon dioxide’s unexpected success lies in partial pressure and high-temperature chemistry. When exposed to the intense heat of the laser melt pool, CO₂ molecules can partially dissociate, releasing oxygen. However, even with this effect, the effective oxygen pressure in a pure CO₂ environment is still lower than the oxygen pressure found in Earth’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere.

In simple terms, oxygen is present, but it is not being forced into the molten metal as aggressively as it is in normal air. This significantly reduces oxidation damage.

The researchers also analyzed the printed parts after production. They found that even parts printed under argon contained small amounts of oxygen. Parts printed in carbon dioxide had about 1.6 times more oxygen content than those printed in argon, but still far less than parts printed in ambient air. This difference turned out to be crucial: the CO₂-printed parts remained structurally functional, while air-printed parts did not.

What This Means for Mars Missions

For future Mars missions, this research has major implications. Transporting consumables from Earth is one of the biggest challenges in space exploration. Every kilogram of cargo adds enormous cost and complexity. If astronauts can use Mars’ own atmosphere as part of their manufacturing process, they can dramatically reduce reliance on Earth-based resupply.

This approach fits squarely within the concept of In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)—the idea of using local materials on other planets to support human activity. Just as future Mars settlers may extract oxygen from CO₂ for breathing and fuel, they could also use that same atmosphere to support metal manufacturing.

A metal 3D printer operating in or near a Mars habitat could allow astronauts to fabricate replacement parts on demand, repair broken equipment, and adapt tools for unexpected situations. Visual perfection would matter far less than functional reliability, and carbon dioxide appears to deliver exactly that level of performance.

Implications Beyond Space

The findings also have potential consequences back on Earth. Argon is costly for industrial users, and shield gas expenses add up quickly in metal additive manufacturing. If CO₂ can be used as a lower-cost alternative for certain non-critical applications, manufacturers could significantly reduce operating costs.

The trade-off would be aesthetics and precision. CO₂-printed parts are less visually appealing and slightly less dimensionally accurate. For many industrial components, however, appearance is irrelevant as long as the part performs its intended function.

The Bigger Picture of Space Manufacturing

Metal 3D printing is already being tested aboard the International Space Station, and agencies like NASA and ESA see in-space manufacturing as a cornerstone of future exploration. Mars presents a much harsher environment, but also offers unique opportunities due to its CO₂-rich atmosphere.

This study does not claim that carbon dioxide can fully replace argon in all applications. Instead, it shows that “good enough” manufacturing may be more than sufficient for survival, maintenance, and long-term habitation on another planet.

By demonstrating that Mars’ atmosphere can be used as part of the manufacturing process, this research brings humanity one step closer to sustainable off-world living—where astronauts are not just visitors, but capable problem-solvers using the resources around them.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.04232