Peering Below Callisto’s Icy Crust With ALMA Reveals New Clues About Jupiter’s Ancient Moon

What lies beneath the frozen, heavily cratered surface of Callisto, Jupiter’s outermost large moon? A recent scientific study has taken a fresh look at this long-standing question using observations from one of the world’s most powerful radio observatories. By analyzing archival data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), researchers have gained new insights into Callisto’s surface temperatures, subsurface structure, and composition, offering a clearer picture of what may exist just below its icy exterior.

The study, led by Cole Meyer and colleagues, has been accepted by The Planetary Science Journal and is currently available as a preprint on the arXiv server. While Callisto is often overshadowed by its more geologically active siblings—Io, Europa, and Ganymede—this work highlights why the moon remains an important target for planetary science.

Using ALMA to Look Beneath the Surface

For this research, the team did not collect new observations. Instead, they carefully analyzed six archival thermal images of Callisto captured by ALMA between July 17 and November 4, 2012. ALMA, located in Chile’s Atacama Desert, is designed to observe the universe in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. These wavelengths are particularly useful for studying thermal emission from cold objects, including icy moons in the outer solar system.

In Callisto’s case, ALMA’s wavelengths allow scientists to probe the top few centimeters of the surface and near-subsurface, offering information that is not easily accessible with optical imaging alone. This shallow depth may sound modest, but it is critical for understanding how heat moves through the moon’s outer layers and what those layers are made of.

Combining ALMA and Galileo Data

A key part of the study involved comparing ALMA data with older measurements from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. Galileo carried the PhotoPolarimeter-Radiometer (PPR) instrument, which previously measured Callisto’s surface temperatures at infrared wavelengths.

By combining these two datasets, the researchers were able to establish a more reliable baseline temperature for Callisto’s uppermost regolith layers. This approach also helped refine earlier models of the moon’s surface properties and reduce uncertainties that existed when relying on a single mission’s data.

Surface Temperature and Thermal Behavior

One of the study’s central findings is an updated estimate of Callisto’s surface temperature. The researchers calculated a disk-averaged surface temperature of about 133 Kelvin, which corresponds to roughly –140 degrees Celsius. This value is consistent with Callisto’s great distance from the Sun and its icy surface composition.

More importantly, the study revealed that Callisto’s surface does not behave thermally as a single, uniform layer. Instead, the data are best explained by a two-component thermal model. One component has low thermal inertia, meaning it heats up and cools down quickly, while the other has much higher thermal inertia, retaining heat more effectively.

This combination suggests that Callisto’s near-subsurface is structurally and compositionally diverse. Differences in grain size, porosity, ice purity, and the presence of darker, rocky material could all contribute to these variations. The researchers also found regional differences in subsurface temperatures, indicating that Callisto’s surface is more complex than it may appear at first glance.

Improving Our Understanding of Callisto’s Regolith

The moon’s surface is covered by regolith, a layer of loose, fragmented material created by billions of years of impacts. Using ALMA data, the team was able to improve existing models of regolith composition across different terrain types, including heavily cratered regions and smoother plains.

These refinements matter because regolith properties influence how heat is stored and transferred, how radiation penetrates the surface, and how future spacecraft instruments might interpret measurements. In other words, understanding the regolith is essential for making sense of nearly all remote-sensing data from Callisto.

Why Callisto Is Scientifically Important

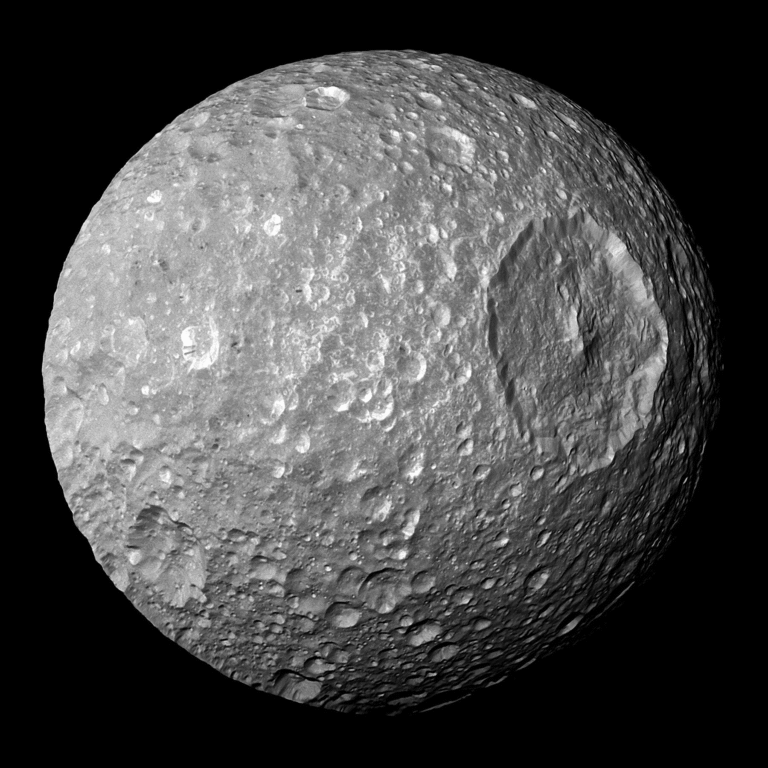

Callisto is the fourth and outermost of the Galilean moons, discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Roughly the size of the planet Mercury, it is widely known as one of the most heavily cratered objects in the solar system. Unlike Io, Europa, and Ganymede, Callisto shows little evidence of internal geological activity, such as volcanism or tectonics.

This lack of resurfacing makes Callisto especially valuable to scientists. Its surface preserves an ancient record of impacts from the early solar system, a time when collisions were far more common than they are today. Studying these craters helps researchers understand how planets and moons evolved during that violent era.

Despite its apparent inactivity, Callisto may still be hiding something remarkable beneath its crust.

The Possibility of a Subsurface Ocean

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that Callisto could harbor a liquid water ocean beneath its icy shell, similar to Europa and Ganymede. This idea comes primarily from measurements of how Callisto interacts with Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field. Variations in the magnetic environment around the moon are consistent with the presence of a conductive, salty liquid layer below the surface.

What makes Callisto particularly intriguing is that, unlike Europa, it does not experience strong tidal heating from Jupiter. If a subsurface ocean exists there, it would demonstrate that liquid water can persist without intense tidal forces, expanding scientists’ understanding of where habitable environments might exist.

Preparing for Future Missions Like JUICE

The study also looks ahead to future exploration. The authors note that dedicated ALMA science observations—rather than archival calibration data—could significantly improve spatial resolution and reduce uncertainties in brightness temperature measurements.

These improvements will be especially valuable for upcoming spacecraft missions, most notably the European Space Agency’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE). JUICE was launched in April 2023 and is currently on its long journey to Jupiter, with an expected arrival in July 2031.

Between 2031 and 2034, JUICE will conduct multiple flybys of Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, studying their surfaces, interiors, and interactions with Jupiter’s magnetic field using a suite of 10 scientific instruments. Although the spacecraft will ultimately enter orbit around Ganymede, it will still collect extensive data on Callisto, building on the groundwork laid by studies like this one.

Looking Beneath Icy Worlds Beyond Callisto

Beyond its immediate findings, this research demonstrates the growing potential of radio and submillimeter astronomy for planetary science. Instruments like ALMA are not just tools for studying distant galaxies and star formation; they are increasingly valuable for exploring the subsurface properties of planetary bodies closer to home.

As techniques improve and new missions arrive at Jupiter, Callisto may finally give up more of its secrets—revealing not just what lies beneath its icy crust, but also how seemingly quiet worlds can still play a major role in our understanding of the solar system.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.15850