Do Even Low-Mass Dwarf Galaxies Merge? New Clues From the Outer Stars of a Milky Way Satellite

Astronomers have uncovered surprising new evidence suggesting that even the smallest and faintest galaxies may have far more complex histories than previously believed. Using the powerful Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, researchers have identified a previously unknown stellar structure surrounding the Ursa Minor dwarf spheroidal galaxy, a tiny satellite galaxy orbiting the Milky Way. The discovery raises an intriguing question: can extremely low-mass dwarf galaxies experience mergers, just like their massive counterparts?

For decades, dwarf galaxies have been viewed as relatively simple systems. Many astronomers considered them fossil galaxies—ancient remnants formed early in the universe that evolved quietly, without much interaction with other galaxies. But this new study challenges that idea and hints that galaxy mergers may be more common, even at the smallest cosmic scales.

A Closer Look at the Ursa Minor Dwarf Galaxy

The Ursa Minor dwarf spheroidal galaxy, often abbreviated as UMi dSph, is one of the Milky Way’s long-known satellite galaxies. It is extremely faint, contains very little gas, and has a mass roughly one ten-thousandth that of the Milky Way. Because of its low mass and lack of ongoing star formation, Ursa Minor has traditionally been considered a quiet and uneventful system.

However, appearances can be deceiving.

An international research team led by scientists from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), along with collaborators from SOKENDAI, Hosei University, and Tohoku University, set out to study Ursa Minor in unprecedented detail. Their goal was to examine the galaxy’s outer stellar regions, where faint clues to its past might still be preserved.

Why the Subaru Telescope Made the Difference

Previous studies of dwarf galaxies relied heavily on data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission. While Gaia has revolutionized our understanding of the Milky Way and its satellites, it has an important limitation: it primarily detects bright stars, such as red giant branch stars. This makes it difficult to trace the distribution of numerous faint stars in the outer regions of dwarf galaxies.

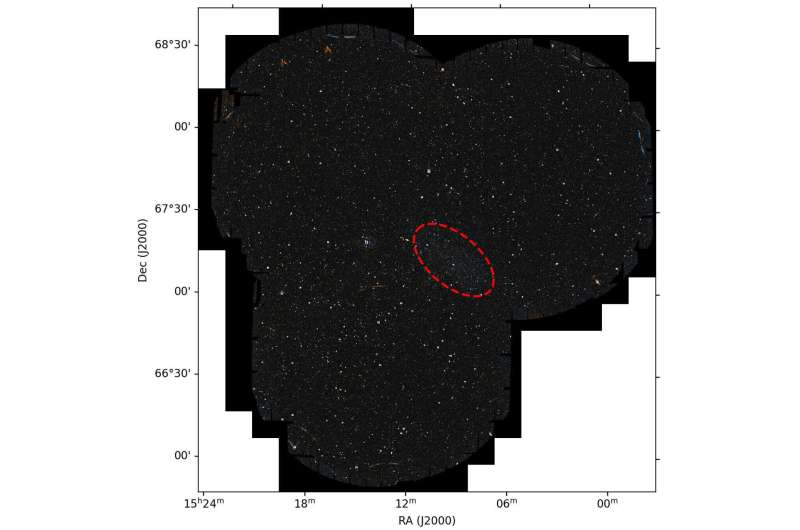

To overcome this, the team used Hyper Suprime-Cam (HSC) mounted on the 8.2-meter Subaru Telescope. This instrument combines an exceptionally wide field of view—covering an area equivalent to nine full moons—with powerful light-gathering capability. That combination allowed astronomers to detect faint main-sequence stars that had been invisible in earlier surveys.

The result was the most detailed map ever produced of the stellar outskirts of the Ursa Minor dwarf galaxy.

A Stellar Structure Beyond Expectations

What the researchers found was unexpected. Stars belonging to Ursa Minor were detected well beyond the galaxy’s nominal tidal radius, the boundary where the Milky Way’s gravity is expected to dominate and strip stars away. Even more intriguing, the stellar distribution extended along both the major and minor axes of the galaxy.

Elongation along the major axis is not entirely surprising. Such features are commonly interpreted as the result of tidal interactions with the Milky Way, which can stretch and distort smaller galaxies as they orbit.

The minor-axis extension, however, tells a different story.

This newly discovered structure along the minor axis shows distinct properties that do not match what astronomers would expect from tidal forces alone. According to the researchers’ analysis, the observed number of stars in these outer regions exceeds theoretical predictions for a galaxy without extended stellar components.

Evidence Pointing Toward a Past Merger

The unusual characteristics of the minor-axis structure suggest a more dramatic origin. One leading explanation is that this extended stellar component may be the remnant of a past merger between dwarf galaxies.

Until now, direct evidence of mergers in such low-mass systems has been extremely rare. Most confirmed galaxy mergers involve large spiral or elliptical galaxies, or at least dwarf galaxies with significantly higher masses than Ursa Minor. Finding potential merger signatures in a system this small is a major shift in perspective.

If confirmed, it would mean that even the tiniest galaxies in the universe are shaped by interactions, not just internal processes like gas inflow, outflow, and star formation.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding how dwarf galaxies form and evolve is crucial to modern astrophysics. In the standard model of cosmology, small structures form first and then merge over time to create larger galaxies. Dwarf galaxies are therefore considered the building blocks of larger systems, including the Milky Way itself.

If low-mass dwarf galaxies can merge with each other, it adds an important layer of complexity to this picture. It suggests that some dwarf galaxies we see today may actually be composites, built from multiple even smaller systems that combined early in the universe.

This discovery also helps explain why some dwarf galaxies show unexpected stellar halos or asymmetries that cannot be fully accounted for by tidal stripping alone.

What Still Needs to Be Confirmed

While the evidence is compelling, the researchers are careful not to draw premature conclusions. To definitively determine whether the newly discovered structure in Ursa Minor is the result of a merger or tidal interaction, astronomers need more detailed data.

Specifically, they will need to study:

- Stellar kinematics, to see how the stars in the outer structure move compared to those in the galaxy’s core

- Chemical abundances, to check whether the stars share the same origin or come from different stellar populations

If the stars in the minor-axis structure show distinct motions or chemical signatures, it would strongly support the merger hypothesis.

Future Observations and What Comes Next

Fortunately, new tools are on the horizon. The Subaru Telescope is set to be equipped with a next-generation spectrograph known as ʻŌnohiʻula PFS. This instrument will allow astronomers to collect detailed spectra of large numbers of faint stars simultaneously, making it ideal for follow-up studies of Ursa Minor and similar dwarf galaxies.

With these observations, scientists hope to uncover whether this hidden structure truly represents the fossil remains of a long-ago galactic collision.

A Broader View of Dwarf Galaxies

This study highlights how advances in observational technology continue to reshape our understanding of the universe. Dwarf galaxies, once thought to be simple and uneventful, are increasingly revealing complex histories written in their faintest stars.

As more dwarf galaxies are observed with deep, wide-field imaging, astronomers may find that Ursa Minor is not an exception, but rather an example of a common and previously overlooked phenomenon.

The universe, it seems, does not reserve dramatic encounters only for its biggest players.

Research paper:

Kyosuke S. Sato et al., The Extended Stellar Distribution in the Outskirts of the Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae0cb3