Stars That Die Off the Beaten Path Are Changing How Astronomers Think About Supernovae

Astronomers are learning that massive stars don’t always explode where we expect them to. A new study focused on the nearby Triangulum Galaxy, also known as M33, reveals that many future supernovae are likely to occur outside dense star-forming clouds, challenging long-held assumptions about how stellar explosions shape galaxies.

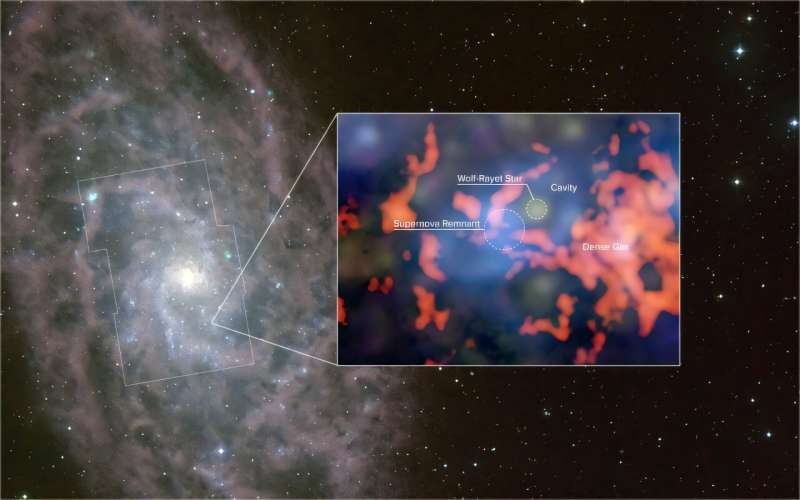

M33 sits about 2.7 million light-years away, close enough for astronomers to map its gas and stars in remarkable detail. By combining new observations of cold atomic gas with detailed maps of molecular gas, researchers have created one of the most comprehensive forecasts yet of where massive stars will eventually explode. Instead of waiting for rare supernova events to happen, the team flipped the problem around: they studied the environments of stars that are already near the end of their lives.

This approach opens a new window into understanding how supernovae influence galaxy evolution, from stirring up gas to spreading heavy elements and regulating future star formation.

Why Where a Star Explodes Matters

Massive stars end their lives in core-collapse supernovae, some of the most energetic events in the universe. These explosions inject enormous amounts of energy and momentum into their surroundings. But the impact of a supernova depends heavily on its environment.

If a star explodes inside a dense molecular cloud, the blast wave cools quickly and deposits much of its energy locally. If it explodes in a more diffuse region dominated by atomic gas, the shock can travel much farther, potentially driving large-scale turbulence and galactic winds. Until now, astronomers have had limited ways to directly study this difference because supernovae are rare and often too distant to resolve in detail.

The new study offers a way around that limitation by identifying future explosion sites in advance.

Mapping the Gas Around Dying Stars

The research team focused on M33 and combined data from two major radio observatories. They used the U.S. National Science Foundation Very Large Array (NSF VLA) to map cold atomic hydrogen gas and paired it with Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observations that trace molecular gas through carbon monoxide emission.

Atomic hydrogen represents the more diffuse component of the interstellar medium, while molecular hydrogen marks the dense clouds where stars form. By mapping both, astronomers can see whether dying stars remain embedded in their birth clouds or have drifted into lower-density regions.

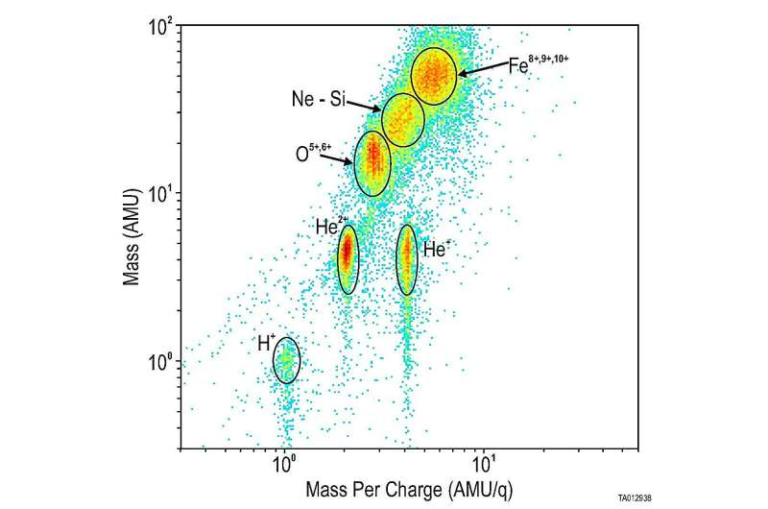

On top of these gas maps, the team overlaid catalogs of three key stellar populations. Red supergiants are bloated, aging massive stars that are known progenitors of most Type II supernovae. Wolf–Rayet stars are hotter, more massive, and shorter-lived, often linked to stripped-envelope supernovae and some gamma-ray bursts. Supernova remnants trace locations where massive stars exploded within the past 10,000 to 100,000 years.

Together, these objects serve as signposts of both past and future stellar explosions.

A Surprising Pattern Emerges

One of the most striking results of the study is that a large fraction of future supernovae will not occur inside dense molecular clouds. Only about 30–40% of red supergiants are found in regions where molecular hydrogen is detected. Supernova remnants show a similar pattern, suggesting that many past explosions also occurred outside dense gas.

Even among Wolf–Rayet stars, which are among the most massive and shortest-lived stars, roughly 45% show no detectable molecular gas at their exact locations. This was unexpected, as these stars are often assumed to explode close to where they formed.

At the same time, nearly all of these objects are still embedded within the broader disk of cold gas. More than 90% are located in regions with detectable atomic hydrogen. This means that while many explosions happen away from dense clouds, they still occur within the galaxy’s gaseous environment, just in lower-density, primarily atomic regions.

What This Means for Supernova Feedback

These findings suggest that many supernova blast waves will expand into relatively empty surroundings before slowing down. In such environments, explosions can travel farther and influence a larger volume of the galaxy. This has major implications for how supernovae inject energy, drive turbulence, and regulate star formation on galactic scales.

It also helps explain why some galaxies show widespread effects from stellar feedback even when star formation appears patchy. Supernovae don’t always detonate in compact clusters; many go off in the surrounding intercloud medium.

A Clear Trend With Stellar Mass

The study also uncovered an important trend linked to stellar mass. The more massive the star, the denser its surrounding gas tends to be. Higher-mass red supergiants and Wolf–Rayet stars are statistically more likely to sit near peaks in molecular gas than their lower-mass counterparts.

This makes sense from a physical perspective. The most massive stars live fast and die young, often exploding before they have time to drift far from their birthplaces or before their natal clouds fully disperse. Still, the study shows that even these stars often occupy complex environments rather than simple, dense clouds.

Cavities Carved Before the Explosion

One detailed example highlights just how misleading lower-resolution maps can be. Using ultra-high-resolution ALMA data, the team zoomed in on a single Wolf–Rayet star. At coarse resolution, the star appeared to lie within a dense molecular cloud. At higher resolution, it was actually sitting inside a roughly 10-light-year-wide cavity carved out of the surrounding gas.

This cavity was likely created by intense radiation, stellar winds, or even a previous supernova. When the Wolf–Rayet star eventually explodes, the presence of this cavity will strongly shape how the blast interacts with nearby material. It’s a reminder that small-scale structure matters when interpreting supernova environments.

Why This Matters for Galaxy Simulations

Large computer simulations are one of the main tools astronomers use to study galaxy evolution over billions of years. Because they can’t resolve individual stars and clouds in detail, these simulations rely on assumptions about where supernovae occur and how their energy is deposited.

The new census from M33 provides real-world data to test those assumptions. By comparing observed environments with simulated ones, researchers can identify where models need refinement, particularly in how they handle radiation, stellar winds, star clustering, and runaway stars.

Observations like these are crucial for improving “subgrid” physics in simulations, ensuring that feedback from stars is treated in a way that matches reality.

The Bigger Survey Behind the Study

The atomic hydrogen data used in this work comes from the Local Group L-Band Survey, a major radio survey targeting nearby galaxies including M33, Andromeda, and several dwarf galaxies. The survey is producing the most sensitive maps of atomic hydrogen ever made for these systems.

Preliminary versions of these maps were used in the current study, with even sharper data already on the way. These improvements will allow astronomers to explore gas structures at finer scales and better understand how stars both form from and destroy the cold gas reservoirs of galaxies.

What Comes Next

The research team plans to expand this work to around 80 additional star-forming galaxies, building a much larger statistical picture of supernova environments. Upcoming ALMA observations of M33 will also provide significantly higher resolution, revealing more cavities, shells, and complex structures around massive stars.

By treating evolved massive stars and recent remnants as markers of future and past explosions, astronomers are steadily piecing together how supernovae sculpt galaxies over time. Instruments like the NSF VLA, ALMA, NASA’s JWST, and the proposed Next Generation Very Large Array will push this work even further.

Stars form from gas, but they also help destroy and redistribute it. Understanding this balance is key to understanding how galaxies like M33, and our own Milky Way, evolve.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.17694