Water Makeup of Jupiter’s Galilean Moons Was Decided at Birth, New Study Reveals

A new scientific study is reshaping how astronomers understand Jupiter’s famous Galilean moons, especially Io and Europa. For decades, scientists have puzzled over why two neighboring moons orbiting the same planet could end up so dramatically different—one bone-dry and violently volcanic, the other icy and likely hiding a global ocean beneath its surface. According to this latest research, the answer is surprisingly simple: they were born that way.

The international study, co-led by researchers from Aix-Marseille University and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), concludes that the stark contrast in water content between Jupiter’s moons was established during their formation, not through billions of years of later evolution. The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal in early 2026 and challenge long-standing assumptions about how moons lose—or retain—water over time.

Why Io and Europa Look Like Complete Opposites

Ever since spacecraft first visited Jupiter in the late 1970s, scientists have known that its large moons are wildly different worlds. Io is the most volcanically active body in the entire solar system, constantly reshaped by massive lava flows and intense tidal heating. Despite being roughly similar in size to Earth’s Moon, Io appears completely dry, with no surface water ice and no evidence of subsurface oceans.

Europa, on the other hand, is almost Io’s mirror image. Its surface is covered in water ice, crisscrossed by cracks and ridges, and multiple lines of evidence suggest it harbors a vast global ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust. That ocean alone may contain more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

Because Io and Europa orbit Jupiter at relatively close distances to each other, many scientists long assumed that their differences must be the result of later evolutionary processes, such as heating, erosion, or atmospheric escape. This new study puts that idea to a rigorous test—and finds it lacking.

Two Competing Theories Put to the Test

The researchers examined two main hypotheses that have been debated for years.

The first hypothesis proposed that Io and Europa formed with similar amounts of water, but Io later lost most of it. According to this idea, intense heat, volcanic activity, and Jupiter’s powerful radiation stripped Io of its volatiles over time, leaving it dry.

The second hypothesis suggested something more fundamental: the moons formed from different materials right from the start. In this scenario, Io accreted from dry building blocks close to Jupiter, while Europa formed farther out from materials that were rich in water and ice.

To figure out which explanation actually works, the research team reconstructed the earliest stages of Io’s and Europa’s evolution using advanced numerical models. These simulations tracked how heat and water behaved inside the moons over time, taking into account all major heat sources active in the young Jovian system.

A Deep Dive Into the Physics of Moon Formation

The models included accretional heating from material falling onto the growing moons, radioactive decay inside their rocky interiors, tidal heating caused by Jupiter’s immense gravitational pull, and the effects of Jupiter’s intense early radiation environment. The team also accounted for volatile escape processes, which describe how gases and water might leak into space over long periods.

Crucially, the researchers assumed that any water present in the moons originally came from hydrated minerals—rocks that chemically bind water—rather than from surface ice alone. This is important because hydrated minerals behave very differently under heat than free water ice.

When the team ran the simulations, the results were clear and consistent. Io simply could not lose enough water to explain its current dry state if it had started out water-rich. Even under extreme conditions, the physics did not allow Io to shed that much water efficiently. The same was true for Europa in the opposite direction—it could not easily lose its water either.

The only explanation that fit the data was that Io formed from dry materials, while Europa formed from water-rich ones.

The Role of Jupiter’s Circumplanetary Disk

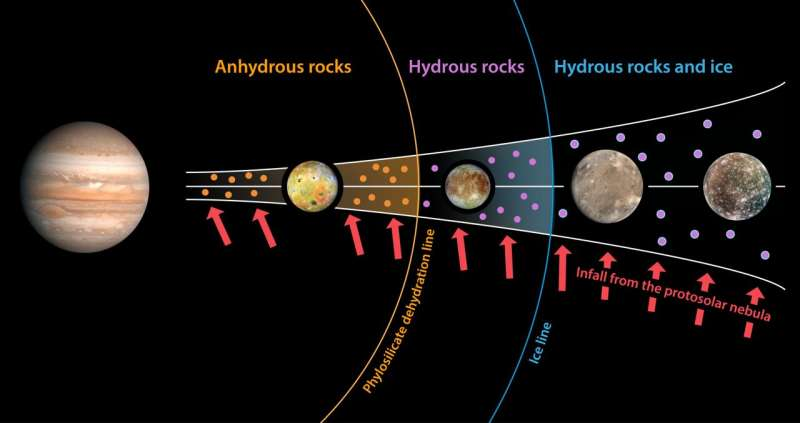

The key to understanding this difference lies in Jupiter’s circumplanetary disk, the swirling disk of gas and dust that surrounded the planet while its moons were forming. Just like the protoplanetary disks around young stars, this disk had temperature gradients—it was much hotter closer to Jupiter and cooler farther away.

The study identifies a so-called dehydration line within this disk. Inside this boundary, hydrated minerals crossing the region would lose their chemically bound water due to high temperatures. Outside it, those same minerals could remain water-rich.

Io formed inside this dehydration line, meaning the material that built it was already dry by the time the moon came together. Europa formed outside the line, allowing it to accrete water-rich minerals and eventually develop its icy shell and subsurface ocean.

This idea helps explain not only why Io and Europa are different, but also why their compositions seem so resistant to change over time.

Why This Matters for Future Missions

These findings arrive at a perfect time. In the coming decade, spacecraft will return to the Jupiter system with far more advanced instruments than ever before.

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, scheduled to begin detailed studies in the early 2030s, will perform dozens of close flybys of Europa. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission will investigate several of Jupiter’s large moons, including Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

One particularly exciting possibility is the sampling of water plumes believed to erupt from cracks in Europa’s icy surface. By analyzing the isotopic fingerprints of that water, scientists may be able to confirm whether Europa’s ocean truly dates back to its formation.

If the water chemistry matches the predictions of this study, it would strongly support the idea that Europa has been wet—and potentially habitable—since the very beginning.

Broader Implications for Planetary Science

Beyond Jupiter, this research has implications for how scientists think about moon and planet formation across the solar system and beyond. It suggests that the environments in which moons form can lock in their most important characteristics early on, leaving relatively little room for dramatic changes later.

The study also challenges the long-standing assumption that high-density bodies like Io must have lost large amounts of volatiles after forming. Instead, density differences may often reflect where and how objects formed, not what they lost afterward.

A Fresh Look at Familiar Worlds

Io and Europa have been studied for decades, yet this research shows that even well-known worlds can still surprise us. By combining detailed physics with modern computational models, scientists are now peeling back the layers of history to understand not just what these moons look like today, but why they ended up that way in the first place.

As new missions prepare to revisit Jupiter’s moons, studies like this one are helping frame the questions those spacecraft will soon help answer.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae2ebd