These Gravitationally Lensed Supernovae Could Finally Help Resolve the Hubble Tension

One of the biggest unresolved problems in modern cosmology is figuring out how fast the universe is expanding. Scientists have known for over a century that the universe is growing larger, but pinning down the exact rate of that expansion has proven surprisingly difficult. This challenge sits at the heart of what researchers call the Hubble tension, and a newly discovered pair of supernovae may offer one of the most promising ways yet to address it.

The expansion rate of the universe is described by the Hubble Constant, named after astronomer Edwin Hubble, who first showed in the 1920s that galaxies are moving away from each other. The problem is that different methods of measuring this constant give different answers. When scientists look at the early universe using the cosmic microwave background, they measure a value of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. When they use nearby objects such as Type Ia supernovae, which act as “standard candles” in the cosmic distance ladder, they get a higher value of around 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec. The disagreement between these two measurements is what defines the Hubble tension.

Astronomers have now identified two ancient supernovae, discovered under exceptional conditions, that could provide a powerful new way to measure the universe’s expansion. These exploding stars are called SN Ares and SN Athena, and they were detected because their light is being strongly gravitationally lensed by massive galaxy clusters lying between them and Earth.

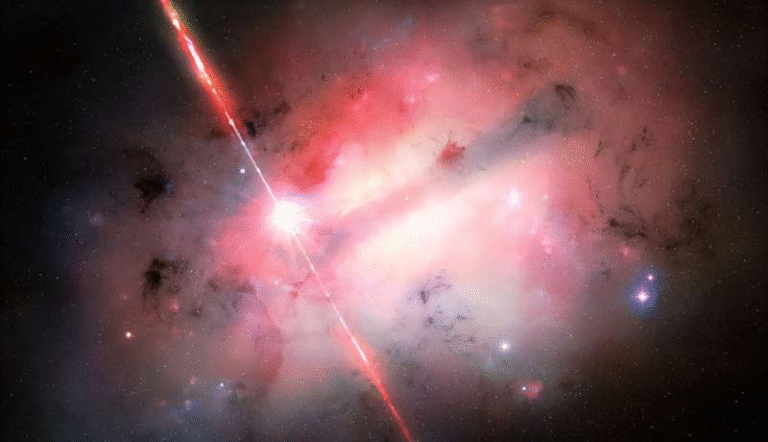

Gravitational lensing occurs when enormous concentrations of mass, such as galaxy clusters, warp spacetime itself. As light from a distant object passes through this warped region, it gets bent, magnified, and sometimes split into multiple images. In the case of SN Ares and SN Athena, the alignment between the supernovae, the galaxy clusters, and Earth is just right for this effect to happen in a dramatic way.

These discoveries were presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and they come from observations made using both the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The work is part of an ambitious observing effort called VENUS, which stands for Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources. Despite the name, the program has nothing to do with the planet Venus. Instead, it focuses on using JWST to study 60 massive galaxy clusters, turning them into natural cosmic telescopes through gravitational lensing.

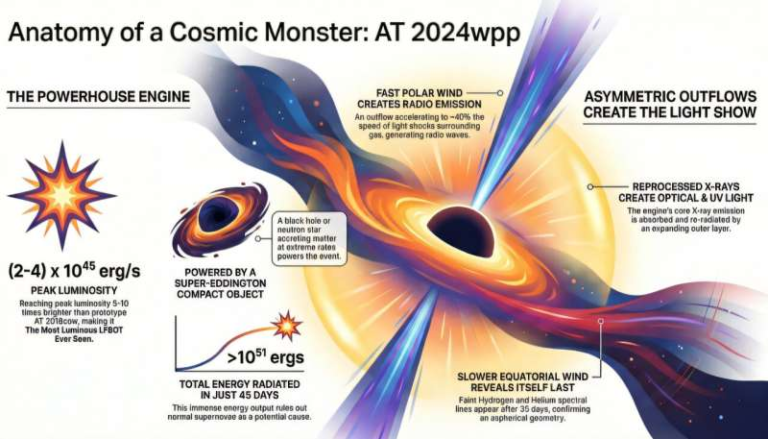

Even though the VENUS program is only about halfway complete, it has already uncovered some remarkable objects. These include individual stars from the early universe, faint active black holes in young galaxies, and now these two rare, lensed supernovae. Events like SN Ares and SN Athena are extremely difficult to detect without lensing, because they occurred billions of light-years away and would otherwise be far too faint.

SN Ares exploded when the universe was only about four billion years old, while SN Athena exploded roughly 6.5 billion years ago. Their light has been traveling toward us ever since, stretched by the expansion of the universe along the way. What makes these supernovae especially valuable is that the lensing galaxy clusters cause their light to arrive at Earth at different times, depending on the path each light ray takes through curved spacetime.

This phenomenon creates a unique opportunity. Because the time delay between the multiple images depends directly on the geometry of the universe and its expansion history, astronomers can use these delays to calculate the Hubble Constant in a way that does not rely on traditional distance ladders or early-universe models.

SN Athena is expected to reappear in additional lensed images within the next two to three years, making it a relatively short-term test case. SN Ares, on the other hand, is far more extreme. Some of its future images are predicted to arrive around 60 years from now, representing one of the longest time delays ever predicted for a lensed supernova. This makes SN Ares a rare opportunity for a truly predictive experiment in cosmology.

The basic idea is simple but powerful. Astronomers use current observations of the supernovae and the galaxy clusters to predict exactly when the next images should appear. When those images do arrive, the difference between the prediction and reality reveals how accurate the assumed value of the Hubble Constant was. Longer time delays lead to tighter constraints, which is why SN Ares is considered especially valuable despite the long wait.

These measurements also tie directly into questions about dark energy, the mysterious component thought to make up roughly 70 percent of the universe and drive its accelerated expansion. Because gravitational lensing time delays depend on the overall expansion history of the cosmos, they can help test whether our current understanding of dark energy is correct or incomplete.

Beyond their cosmological value, SN Ares and SN Athena also offer insights into supernova physics in the early universe. JWST was able to collect spectra from these explosions, allowing astronomers to study how massive stars lived and died billions of years ago, under conditions very different from those in the modern universe.

These discoveries also highlight the growing importance of time-domain astronomy, a field that focuses on objects that change over time. In this case, the changes are not happening in real time from the explosion itself, but in the delayed arrival of light across decades. Few astronomical events combine such vast timescales with such precise physical measurements.

While it may take decades for SN Ares to fully deliver its scientific payoff, SN Athena will provide meaningful data much sooner. Together, they represent a new and independent path toward resolving the Hubble tension. Depending on what these measurements reveal, they could either support the idea that new physics is needed beyond the standard cosmological model or uncover hidden systematics in existing measurement techniques.

For now, these gravitationally lensed supernovae stand as some of the most promising cosmic tools yet discovered for understanding how fast the universe is expanding and why different methods disagree. As more lensed supernovae are found through programs like VENUS, astronomers may finally be closing in on one of cosmology’s most persistent mysteries.

Research paper and study reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.XXXX